Financially reviewed by Patrick Flood, CFA.

Inflation fears are always lingering. Here we'll look at what inflation is, why it occurs, how it's measured, and the best assets to hedge against it with their corresponding ETFs for 2024.

Disclosure: Some of the links on this page are referral links. At no additional cost to you, if you choose to make a purchase or sign up for a service after clicking through those links, I may receive a small commission. This allows me to continue producing high-quality, ad-free content on this site and pays for the occasional cup of coffee. I have first-hand experience with every product or service I recommend, and I recommend them because I genuinely believe they are useful, not because of the commission I get if you decide to purchase through my links. Read more here.

Contents

Video

Prefer video? Watch it here:

Introduction – What Is Inflation?

Simply put, inflation refers to an aggregate increase in prices, commonly measured by the Consumer Price Index (CPI). Put another way, purchasing power decreases as inflation increases. This means that for any given unit of currency, in this case the U.S. Dollar, you're able to buy fewer goods and services as time goes on.

Average annual inflation in the United States is about 2%. This is why it's usually advisable to not hold a significant allocation to uninvested cash, as it's likely simply “losing to inflation.” This is especially true recently, as inflation has been much higher around 7%:

Inflation is illustrated in the stories your parents tell of being able to go the movies and get popcorn and a drink for 25 cents 40-50 years ago, whereas it's about 100x that today.

A central bank manages the money supply to attempt to keep inflation within a reasonable limit. This reasonable level of inflation is maintained because it encourages people to spend now, thereby promoting economic growth, rather than saving, as a dollar today is worth more than the same dollar tomorrow on average.

This somewhat constant level of inflation helps maintain price stability (think better planning for the future for both businesses and consumers) and is thought to maximize employment and economic well-being. Investors expect returns greater than this “reasonable,” average level of inflation, and workers expect wage increases to keep pace with the increasing cost of living.

How Is Inflation Measured?

Inflation is typically measured by two common statistics – the Consumer Price Index (CPI), a measure of the price in aggregate of consumer goods and services (e.g. food, apparel, education, etc.), and the Wholesale Price Index (WPI), a measure of the price of goods at the production level. Instead of the WPI, the United States uses a similar index called the Producter Price Index (PPI). CPI is used to measure cost of living.

All these are tracked, maintained, and reported by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. They report the CPI monthly going back to 1913. You can even narrow down CPI by region within the U.S.

When people reference the “inflation rate,” they're referring to the CPI.

Why Does Inflation Occur?

Inflation can occur as any of the following:

- Demand-Pull Inflation: In short, demand exceeds supply, causing upward pressure on prices, also colloquially described as “too many dollars chasing too few goods.” Recall Keynesian economics and the supply vs. demand curve from microeconomics. Demand-pull inflation can be caused by things like a growing economy, an increase in the money supply, and an increase in government spending.

- Cost-Push Inflation: Increases in wages and production costs (e.g. raw materials) necessarily drive prices up, while demand for goods and services stays constant or increases.

- Built-In Inflation: Built-in inflation simply describes the fact that people expect inflation to continue to gradually rise, so firms continually raise prices to keep pace. Because of this increase in prices, consumers demand higher wages to keep up with a rising cost of living, which in turn causes firms to raise prices, and the cycle continues.

Annual Rate of Inflation Formula – How To Calculate

We can calculate the annual rate of inflation – or the change in prices for any time period – using CPI values with the following formula:

Inflation Rate = [(Final Index Value) / (Initial Index Value) - 1] * 100Here's an example. The annual CPI was 255.7 for 2019 and 258.8 for 2020. We can calculate the annual inflation rate like this:

Inflation Rate = (258.8 / 255.7 - 1) * 100 = 1.25%Similarly, we can see what the purchasing power of $1,000 in 1970 is in 2020 like this:

258.8 / 38.8 * $1,000 = 6.67 * $1,000 = $6,670Why Is Inflation Good?

Inflation can be good for owners of real assets like real estate and commodities, as a rise in their prices means they can be sold for a gain later. Of course, this benefits the owner/seller at the detriment of the buyer.

The aforementioned “reasonable” level of Inflation is generally also a sign of a healthy, growing economy, as it encourages more current spending and investment. This is why it's desirable to maintain that reasonable level of gradual inflation.

Why Is Inflation Bad?

As opposed to assets priced in the inflated currency, inflation eats away at the value of assets denominated in the inflated currency, such as cash and nominal bonds (particularly longer term bonds with more interest rate risk).

The prospect of variable or high/rapid inflation introduces uncertainty to both the economy and the stock market, which doesn't really benefit anyone. This uncertainty or variable inflation distorts asset pricing and wages at different times. Prices also tend to rise faster and earlier than wages, potentially contributing to economic contraction and possible recession.

How To Control Inflation with Monetary Policy

A country's monetary policy helps maintain “healthy” levels of inflation. In the U.S., that responsibility falls largely to the Federal Reserve Bank or simply “the Fed.” Again, the Fed attempts to keep inflation within reasonable limits in order to maximize employment, stabilize prices, and encourage spending. The main levers they can pull to achieve this are influencing interest rates and the money supply. A whole post (or a whole book) could be dedicated to this topic alone, but I'll keep it to a brief high-level summary.

Specifically, the Fed usually buys treasury bonds to inject cash into the economy, known as quantitative easing, or QE for short. The target rate of inflation in the U.S. is about 2%. QE is typically ramped up when interest rates are at or near zero, as the Fed then has fewer tools with which to act.

This is somewhat of a balancing act, though, as the Fed merely hopes to influence economic activity; it cannot force lenders and borrowers to do anything. Moreover, the Fed's increasing the money supply can lead to stagflation – inflation without economic growth – and a devalued currency, which makes imports more expensive. This itself can again drive up production costs and subsequent consumer prices, and thus inflation may accelerate beyond the Fed's target levels.

Inflation Examples

When people think of famous examples of inflation, they're almost always cases of hyperinflation, defined as an inflation rate of more than 50% per month. Hyperinflation is extremely rare in developed countries. Here are a few famous examples of hyperinflation throughout history:

- Hungary – 1945-1946 – Hungary at one point saw daily inflation of 207% after the government tried to use inflation to restore the economy after World War II.

- Zimbabwe – 2007-2008 – full-blown hyperinflation at a daily rate of 98% that followed many years of high inflation around 40% annually as a result of reckless government spending. Zimbabwe was forced to eventually abandon its currency altogether.

- Yugoslavia – 1992-1994 – a result of the dismantling of trade following the breakup of Yugoslavia.

- Greece – 1944 – a result of huge sovereign debt from World War II and tax revenues dwindling.

- Germany – 1923 – Hyperinflation of the Weimar Republic is one of the most famous examples in history, resulting from the government basically printing money to pay war reparations.

Inflation Hedges – Do You Even Need Them?

People seem particularly concerned with “inflation” nowadays and how they can “hedge” against it. I put those words in quotes because when people discuss or fear “inflation” (and how to hedge against it), they usually mean above-average inflation. Remember, inflation per se is essentially always happening at a relatively steady rate that we hope stays around 2% per year (at least in the U.S.).

Financial pundits writing headlines about “inflation fears” are intrinsically referring to the prospect of inflation that is greater than or faster than the average rate. The important distinction I want to make is simply that any “hedge against inflation” one hopes to adopt is to mitigate the potential negative impact of unexpected, above-average inflation.

Why is this distinction important? Recall the Efficient Markets Hypothesis, the idea that all known information is already incorporated into the prices of assets. Many investors perhaps don't realize that the steady, constant, expected inflation we've discussed is already baked into the prices of stocks and bonds, so annual inflation continuing as it has does not necessarily hurt your portfolio, and you don't need a “hedge” (or portfolio protection) for it.

Moreover, know that an extended above-average inflationary environment in the U.S. is pretty rare. We haven't seen one since the 1970's, before the Volcker era when there was a fundamental shift in U.S. monetary policy. In fairness, we are currently seeing unprecedented levels of low bond yields and high stock valuations which could arguably contribute to a greater propensity for above-average inflation, but I'd be willing to bet that it would be short-lived.

Because of all this, arguably the best “hedge” for inflation is simply greater portfolio returns, usually achieved by a stocks-heavy portfolio, as stocks have the greatest expected returns of any asset class. That is, as with assets like gold, any dedicated allocation to an asset as a purported “inflation hedge” will likely simply drag down your long-term total return. More on this in a bit.

Moreover, any allocation taken up for that purpose should probably be relatively small, as again we're talking about a pretty unlikely scenario that will likely be short-lived. Don't miss the forest for the trees. I would submit that buy-and-hold investors with a long time horizon and a moderate to high risk tolerance should ignore the short-term noise anyway and likely don't need any dedicated position as an inflation hedge, despite what the fearmongering headlines from the pundits in the financial blogosphere say.

However, as usual, retirees or those with a short time horizon or low risk tolerance may find this typical tradeoff between risk (and specifically, short-term volatility) and return perfectly acceptable and desirable, and that's fine (and appropriate). Unexpected inflation can also be particularly damaging for these investors. The next section is for them.

How To Hedge Against Inflation – Assets and ETFs

So for those who do want to specifically protect (“hedge”) their portfolio against above-average inflation, which assets are best? First, let's talk about what we're looking for and hoping to achieve with an “inflation hedge.”

Just as one might buy put options as a direct hedge for a bullish stocks position as somewhat of a short-term insurance policy if the investor fears an impending crash in the short-term, an ideal inflation hedge would increase in value to a greater degree than the CPI itself precisely when called upon, acting as an insurance policy against rapid rising inflation. Sounds great, right? Where do I sign?

Unfortunately, I've got some bad news: No such asset exists.

So the phrase “inflation hedge” is sort of a misnomer. Now you see why I said earlier that the ironic, perhaps counterintuitive answer for the “best inflation hedge” over the long term may just be plain ol' stocks (and a stable job), providing the greatest returns for your portfolio leading up to and following an inflationary period, thereby allowing your portfolio's value to weather future storms more easily. In that sense, you're likely already covered.

But we know that above-average inflation still devalues our uninvested cash and nominal bonds in the short term, which is an important consideration for the retiree due to sequence risk, and we also know risk is experienced over the short term. So what about assets that can keep pace with (match) the CPI or simply perform comparatively well during inflationary periods? Let's look at some options.

Real Estate

Inflation means higher prices for real assets, one of which is real estate. This means higher property values. Landlords can also directly pass on inflation costs to tenants in the form of higher rents. This applies to both physical property owners and REIT investors.

Though it's debatable, real estate may also offer a small diversification benefit to one's investment portfolio while not necessarily sacrificing returns.

VNQ is a popular REITs ETF from Vanguard.

Commodities

Similarly, commodities are a tangible asset as well. Commodities are simply means of production – oil, gas, copper livestock, etc. Just like with real estate, the value of these things goes up with inflation.

However, I've written elsewhere how commodities are not a value-producing asset so they have a long-term expected real return of about zero, commodities funds are expensive, and there are better alternatives for inflation-protected assets in my opinion.

The legendary Ken French maintains a similar position:

The claims that, going forward, commodity funds (i) will have the same Sharpe ratio as the stock market, (ii) will be negatively correlated with the returns on stocks and bonds, and (iii) will be a good hedge against inflation can't all be true. Who would want the other side of this trade? The high volatility of commodity prices makes it impossible to accurately estimate the expected returns, volatilities, and covariances of commodity funds, but theory suggests that if commodity returns are negatively correlated with the rest of the market, the expected risk premium on commodities is small, perhaps negative. Finally, commodity funds are poor inflation hedges. Most of the variation in commodity prices is unrelated to inflation. In fact, commodity indices are typically 10 to 15 times more volatile than inflation. As a result, investors who use commodity funds to hedge inflation almost certainly increase the risk of their portfolios.

For those who do want exposure to broad commodities, PDBC from Invesco is the most popular broad commodities ETF and conveniently does not generate the dreadful K-1 form at tax time.

Gold

While we're on the subject of commodities, the most popular one is gold. The shiny metal is often touted as an inflation hedge, but unfortunately it hasn't been a reliable one historically.

Just like broad commodities, gold is also not a value-producing asset, so we wouldn't expect it to generate a return over the long term. Remember what I said about an inflation protection asset likely simply dragging down the returns of the portfolio over the long term. Gold is also taxed as a collectible.

I would submit that gold has no place in a long-term investment portfolio unless the investor is very risk-averse and simply wants to minimize volatility and drawdowns, as gold does tend to be uncorrelated to both stocks and bonds. For those that do want gold, SGOL is a suitable ETF that tracks the spot price of gold bullion.

Stocks

As I've already said, stocks are a great inflation “hedge” simply due to their greater expected returns over the long term, not because they tend to do well during periods of high unexpected inflation (they don't). Specifically too, “defensive” sectors like Consumer Staples and Utilities tend to weather inflationary and recessionary periods better than others, as public demand for these goods and services typically remains unchanged (which is why they're called non-cyclical).

Value stocks in general tend to beat Growth stocks during these periods as well, which is icing on the cake for investors like me who already tilt small cap value. Once again, roads point to factor tilts.

As usual, this is also a case for global diversification in stocks, as one country's inflation issues may not affect another.

Vanguard's global stock market ETF is VT.

Debt

Purchasing power decreases with inflation because the value of the currency drops, but this also means that any nominal debt you have is now worth less in real terms. Periods of above-average inflation are a great time to have a mortgage. Mortgage-backed securities (MBS) are an option for those that don't; they're conveniently included in a total bond market ETF like Vanguard's BND.

Short-Term Bonds

I thought you said inflation hurts nominal bonds! Yes, but not all bonds are created equal. Short-term bonds are less sensitive to interest rate changes because you can quickly roll them over into new bonds at higher yields after they mature, and a bond held to maturity should return its par value plus interest.

T Bills (ultra short term treasury bonds of 0-3 month maturities) even essentially kept pace with inflation during the double-digit inflation of the 1970's in the U.S.! There have also been plenty of periods where 1-month T Bills outperformed the stock market. While T Bills are quite literally the “risk-free asset,” they're no slouch. We would expect their returns to be slightly higher than inflation, and indeed they have been historically. The annualized historical return of 3-month T Bills from 1928-2020 was 3.32%. The average inflation rate over that period was 3.02%, which means a real return (return adjusted for inflation) of 0.3%.

While we wouldn't want to hold a significant allocation in cash equivalents over the long term, they provide a decent buffer over the short term for unexpected inflation. A popular short-term treasury bond ETF (1-3 year maturity) from Vanguard is VGSH. Those seeking true T Bills (0-3 month maturity) can use SGOV from iShares.

TIPS

The only asset truly linked to inflation is a relatively new financial product called Treasury Inflation Protected Securities, or TIPS for short, which launched in the U.S. in 1997.

In short, TIPS are U.S. Treasury bonds that are indexed to the CPI, so they rise in tandem. This is precisely what we want in an inflation protection asset. The tradeoff, of course, is their limited long term return. If inflation matches or is lower than aggregate investor expectations, TIPS will have lower returns than nominal bonds. If inflation is higher than expected, TIPS will have higher returns than nominal bonds.

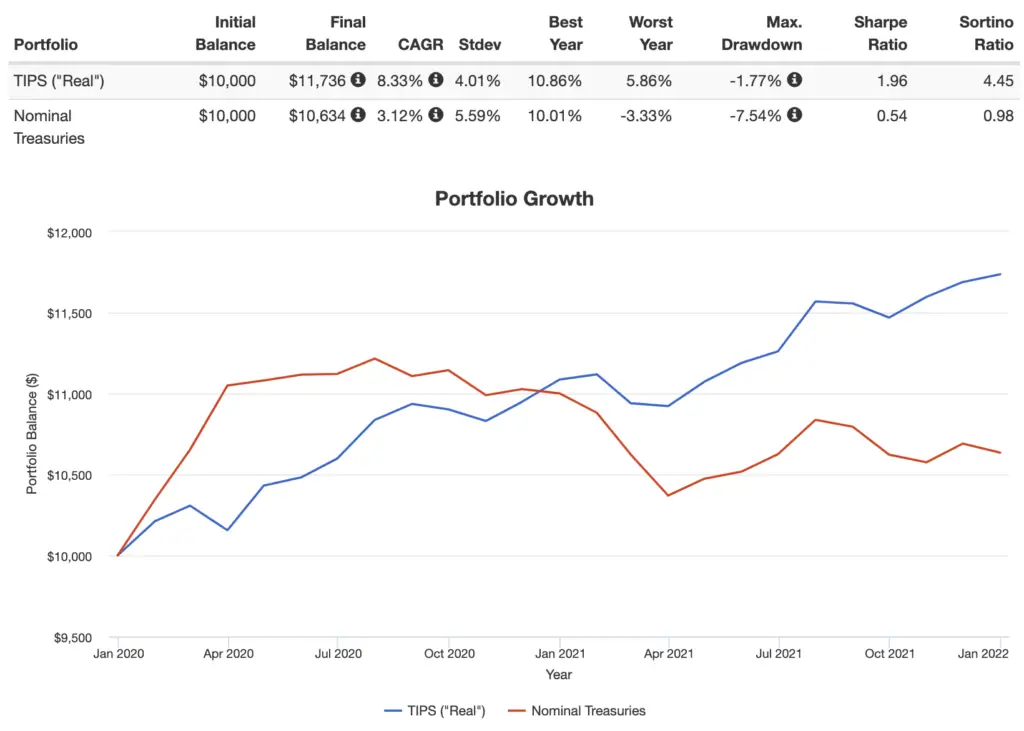

Unfortunately TIPS did not exist in the U.S. during the runaway inflation period of the late '70s, but one can look at the last couple years of above-average inflation (2020-2021) to see TIPS doing their job. Below I've compared intermediate TIPS (also referred to as real bonds) to intermediate nominal bonds of the same duration using live funds for that time period:

A general rule of thumb for a retiree is to consider putting at least half of their fixed income allocation in TIPS, as high unexpected inflation can be disastrous for the retiree's portfolio, from which withdrawals are being made regularly to cover expenses and to which no new deposits are flowing. That's why I included TIPS in my design of an emergency fund replacement portfolio.

It's worth noting though that TIPS do not seem to exhibit the same “crisis alpha” (i.e. “flight to safety” behavior) that nominal treasury bonds do during stock market crashes, which I delved into here. The retiree should also probably have a decent allocation to short- or intermediate-term nominal bonds. Again, I think a 50/50 split is sensible.

TIPS obviously become more important for retirees and those with a bond-heavy portfolio, and are less attractive for younger investors with a long time horizon, but different funds exist to match the TIPS duration to the investing horizon. A popular ETF for short-term TIPS is VTIP from Vanguard. SCHP from Schwab is a good, low-fee option for intermediate-term, and LTPZ from PIMCO for long-term.

I'll also toss Series I savings bonds in here since they're similar to TIPS. I've got a separate post on them here.

Conclusion

Inflation is always happening, hopefully at a steady rate, kept on the rails by a central bank. This expected inflation is already incorporated into asset prices. What we're concerned with possibly protecting against is unexpected above-average inflation.

Even then, an investor with a long time horizon and a high tolerance for risk – and subsequently, a high allocation to stocks – likely shouldn't be worried about short-term inflation. However, it's perfectly suitable and even desirable for retirees, risk-averse investors, and those with a short time horizon to have some allocation to inflation-protected assets like TIPS.

While it may go against what you've heard, commodities and gold may not be great assets to save your portfolio from runaway inflation in the future, and are almost certainly suboptimal investments over the long term. I would submit that investors will likely come out ahead using assets like REITs, short-term nominal bonds, and TIPS. I'm not a fan of sector bets (they're just stock picking lite), but it may also be prudent to slightly overweight “defensive” sectors like Consumer Staples and Utilities if one fears inflation (or any market turmoil, for that matter).

How do you approach inflation in your portfolio? Let me know in the comments.

Disclaimer: While I love diving into investing-related data and playing around with backtests, this is not financial advice, investing advice, or tax advice. The information on this website is for informational, educational, and entertainment purposes only. Investment products discussed (ETFs, mutual funds, etc.) are for illustrative purposes only. It is not a recommendation to buy, sell, or otherwise transact in any of the products mentioned. I always attempt to ensure the accuracy of information presented but that accuracy cannot be guaranteed. Do your own due diligence. I mention M1 Finance a lot around here. M1 does not provide investment advice, and this is not an offer or solicitation of an offer, or advice to buy or sell any security, and you are encouraged to consult your personal investment, legal, and tax advisors. All examples above are hypothetical, do not reflect any specific investments, are for informational purposes only, and should not be considered an offer to buy or sell any products. All investing involves risk, including the risk of losing the money you invest. Past performance does not guarantee future results. Opinions are my own and do not represent those of other parties mentioned. Read my lengthier disclaimer here.

Are you nearing or in retirement? Use my link here to get a free holistic financial plan from fiduciary advisors at Retirable to manage your savings, spend smarter, and navigate key decisions.

Don't want to do all this investing stuff yourself or feel overwhelmed? Check out my flat-fee-only fiduciary friends over at Advisor.com.

Hello, I like the idea of equity being one of best inflation hedges over the long run. What do you think about SCHD as a option to protect (and tilt) against inflation? How can I compare with XLP+XLU which would perform better?

Good Article as usual.Glad you made some mention of the special investment needs of those at or nearing retirement. A full article and portfolio for retirees woiuld be nice…

Also special praise for your habit of replying to commenters on all your articles. That is pretty rare and much appreciated!

Thanks for the kind words, Charles! I presented sample retirement portfolios in my Ginger Ale and Tail Risk posts and I did a post on the best ETFs for retirement, but I guess you’re right that I don’t have an entire post dedicated to retirement.

I’m interested in your take on recent inflationary trends which seem to be (at least initially) largely driven by supply-side shortages linked to COVID.

I ask because I don’t dismiss recent inflation as being inherently short-term since I lived through the 70’s and saw changes in monetary policy (along with OPEC) initially drive inflation which in short order became structural inflation that Volker finally had to break through some truly draconian measures (as an aside, I had the pleasure to meet Paul Volker in the early 80’s—nice guy!)

Clearly the Fed has the same tools used by Volker, but do you see someone out there in the Fed that has the backbone of Volker to actually use them?

Thanks for the comment, Don. Admittedly probably not well versed enough on monetary policy per se to intelligently speak on or predict the specifics. Will be interesting to see how it plays out. But a big difference between now and the 70’s is right now we don’t have high unemployment.

Your comments on gold are incorrect. It is the only investment denominated in US DOLLARS THAT ACTUALLY INCREASES when the dollar is debased by the government. You completely ignore the fact of declining dollar purchasing power.

“Declining dollar purchasing power” is the definition of inflation. Gold should keep pace with it – which means a real return of zero – but only over the very long term, which makes it at least suboptimal for most investors. Even then, there’s no guarantee of that. I noted all this above and linked a relevant landmark study on the topic, so I’m not sure what you’re claiming I “ignored.”

With respect to inflation, how would you compare an S&P 500 fund such as Vanguard VOO to Schwab’s dividend-oriented value fund, SCHD? In addition, would SCHD hold up better in a downturn?

Impossible to know the future. But on average, historically, funds with positive loading on Value and Profitability like SCHD have indeed fared better during downturns. But that has little to do with inflation. Conveniently, these stocks do tend to do better during periods of unexpected inflation as well, as their debt is then worth less.

You need to do a little more homework on gold. Long term investors in gold outperform the market hands down.

If you meant head to head performance, that’s false.

More importantly, past performance does not indicate future performance. Watch out for outcome bias.

The cause of inflation is when the Federal Reserve expands the money supply in excess of the growth of the economy – rising prices are a symptom. Another cause is when the Federal Reserve manipulates interest rates and causes false demand. We have both in gross excess and thus are surrounded by asset bubbles. The only solution is to withdraw the excess money supply and rates interest rates because they were the cause of present inflation. It is only transitory when a temporary increase in demand exceeds supply and corrects when this corrects and equilibrium is reached. Inflation is NEVER good. Only a return to the gold standard will save this country.

Wrong, wrong, and wrong. QE is not inflationary; it’s just a net-zero swap of assets. The Fed does not “manipulate” interest rates; they set the overnight borrowing rate and hope for the best. Would love to hear (but not really) how you propose we return to the gold standard in specific, realistic, practical terms. Perhaps you should throw your hat in for Fed chairman. Thanks for the comment, Gordon. Please read up on macroeconomics and monetary policy – and understand how comment moderation/approval works – before sending me any more accusatory emails.

You don’t know what you are talking about. Why before Nixon took us off the gold standard could you exchange an ounce of gold for $35 and now you can for $1,830 ?

You ignore purchasing power and dollar debasement.

Responded here.

What do you think about high yield bond ETFs, USHY for instance? I would like to keep some cash on the sidelines but I dont want to deal with the erosion of bond prices that has been the result of the recent increases in treasury yields. I am 85%+ invested in stocks and feel overextended due to valuations and the expected pullback in FED bond purchases. I am looking to trim back slightly to maybe 80% exposure but do not want to be in cash because of inflation. Also, I would like to potentially benefit to some extent from a correction by having some money to buy growth stocks at reduced prices (I know, it is market timing to some extent but all decisions have some aspect of timing). My concern is that high yield prices, while holding up well to recent scares, could fall steeply and overall performance would be worse than cash.

Short treasuries and TIPS. Corporates – especially junk bonds – are just a halfway point between stocks and treasuries.

Just know that in doing so, you’re just taking up a more conservative asset allocation for a correction that may not come for years. As you seem to already know, on average you should not hold cash on the sidelines or try to time the market.

What does “hold cash on the sidelines” mean? If you trade your cash for stocks, isn’t somebody else getting your cash for their stocks? The cash is never really “on the side lines”, it’s just in somebody else’s account. Does the value of holding cash change at all depending on how much aggregate debt/margin is outstanding? Cash positioning gets such a bad rap in portfolios. Is it simply because of inflationary monetary policy?

Aaron, what I meant by that phrase is holding cash in a plain savings or checking account to invest later.

You may wish to check out the “Best ways to protect against inflation?” Topic in the RR Community. There Swedroe goes into detail on his perspective on Inflation and what he personally invests & recommends investing into others. With that said, unfortunately, his “big changes have been to add more unique sources of risk including now life settlements where you have no economic cycle risk and big illiquidity premium, but only in private vehicles, where manager selection is very important”. So vehicles where an individual would need millions of dollars.

Aside from that, he noted being 100% SV and he has “a preference for int’l over US because of valuations AND problem of massive fiscal and trade deficits could lead to dollar getting hit and if inflation picks up and you get central banks selling that could be a real risk. So might want to “sin a little” and overweight int’l relative to say 50/50 market.”

Thanks for the suggestion, Daniel. I must have missed that thread. Will check it out.