Market timing refers to trying to predict future market movement to buy or sell at the best price. Here we'll look at why it doesn't work, and why you should stay the course and go ahead and invest as soon as possible to maximize time in the market. In short, time in the market beats timing the market. I'll show you why below.

Disclosure: Some of the links on this page are referral links. At no additional cost to you, if you choose to make a purchase or sign up for a service after clicking through those links, I may receive a small commission. This allows me to continue producing high-quality content on this site and pays for the occasional cup of coffee. I have first-hand experience with every product or service I recommend, and I recommend them because I genuinely believe they are useful, not because of the commission I may get. Read more here.

Contents

Market Timing Video

Prefer video? Watch it here:

Introduction – What Is Market Timing?

Market timing describes the speculative strategy of trying to time one's trades based on predictions about future market movement. While this could apply to selling, we're usually talking about the buy side, where the investor is deciding when to enter a position.

Market timers believe they can outsmart the market and buy at a low point, for example, to later sell at a high point (buy low, sell high), instead of possibly buying at a high point by accident. Market timers may believe a particular market is overvalued and will delay their trades until they think the market has “cooled off.”

Proponents of market timing will claim that their forecasting of price movement will lead to superior outcomes in the form of higher returns. Timing the market is obviously the lifeblood of the day trader, but oftentimes long term investors also sit on cash while waiting for a market dip, which is market timing as well. That is, even the long-term buy-and-hold investor buying passive index funds can still succumb to recency bias.

Time In the Market Beats Timing the Market

So market timers try to get the best price by predicting market behavior so that they can buy low and sell high. Sounds great, right? What's wrong with that?

Unfortunately, just like with stock picking versus passive indexing, the evidence overwhelmingly suggests that successfully timing the market is all but impossible, for the simple reason that market movement is essentially random and unpredictable, as all available information is already priced in. All crystal balls are cloudy, and one cannot expect to accurately and consistently time the market. In fact, the practice is usually more harmful than helpful.

As usual, psychology and emotions play a huge role here. Investors may feel that their investments are “due for a correction” after flying high, or that they're due for a comeback after a recent drop, but nothing says the investment can't continue going up or down respectively. The first investor may shave off some profits to lock in their gains, but their original thesis about the future growth of the investment hasn't changed, so this is irrational behavior. Alternatively, that same investor may believe the recent run up means the stock is on a hot streak, so they buy more; this is equally irrational. On the other side of the coin, the same can be said about panic selling in a crash. These irrational, emotion-based trades are more likely to hurt the investor's long term total return. Fear and overconfidence can be massively damaging to one's portfolio.

Studies suggest that “time in the market” is the way to go. That is, as I've said before, invest early, hold for the long term, and ignore the short term noise. Stay the course, as Jack Bogle said. In doing so, we're relying on the simple premise that the market tends to go up more than it goes down, so we don't need to try to time its movement. As long as the fundamental reasons for investing in the first place haven't changed, the “time in the market” investor simply keeps buying regularly, regardless of market sentiment or valuations.

Moreover, the market spends a non-trivial amount of time at all time highs, which are usually not followed by major dips, so there's no logical reason to sit on cash in fear of a crash just because the market is looking good. In doing so, market timers usually simply miss out on those gains on the way up. The common saying now is that “time in the market beats timing the market.”

This concept is very closely related to the idea of dollar cost averaging vs. lump sum investing. The former describes spreading out a sum of cash over regular intervals. The latter describes investing the total sum all at once as soon as it's available, which is demonstrably superior on average. In this sense, dollar cost averaging – or DCA for short – is like market timing, in that the DCA investor usually fears an impending crash and wrongly believes that sitting on investable cash and averaging that money into the market is safer and will provide a superior outcome. The lump sum investor ignores their feelings about the short-term future of the market.

While we have loads of evidence illustrating the futility of active management and market timing, their allure persists, largely due to behavioral biases. Ironically, the market timer is likely to continue trying to time the market due to hindsight bias, for example, which means humans tend to remember their past predictions as more accurate than they really were. Loss aversion plays a huge role here too – the principle that people are more sensitive to losses than to gains, suggesting that we tend to do more to avoid losses than to acquire gains. Market timers may realize they can't beat the market, but they still think they can avoid losses by sitting on the sidelines waiting for a crash that may never come.

The Costs of Market Timing

There are several important explicit and implicit costs of trying to time the market that illustrate its suboptimality as an investing strategy on average.

The first is fees. Granted, many modern brokers are adopting a fee-free trading model, but if you happen to be with one that still charges commissions on trades, you're incurring one every time you time the market or dollar-cost-average in, as opposed to a single one up front on a single lump sum buy order. You're also taking on the bid-ask spread with each new trade as well. Tiny basis points add up over the long term. This cost is exacerbated in a taxable environment because you may be creating taxable events with your trades.

An implicit cost of market timing is your time. If you're trying to predict market movement to buy low and sell high, any extra analysis and subsequent trading you have to do is an implicit opportunity cost where you could have been doing something else. If you spend 1 hour per week charting and placing buy orders, for example, that's 52 hours per year spent on something that is very likely providing no benefit and is actually hurting your total return over the long term.

The most significant cost that I briefly mentioned earlier is missing out on market gains while sitting on cash, which intrinsically makes the investor's asset allocation more conservative. This is again the main reason why lump sum investing beats dollar cost averaging on average, but the point is even more important in this context, as the market timer may be sitting on cash for months or even years in anticipation of a crash.

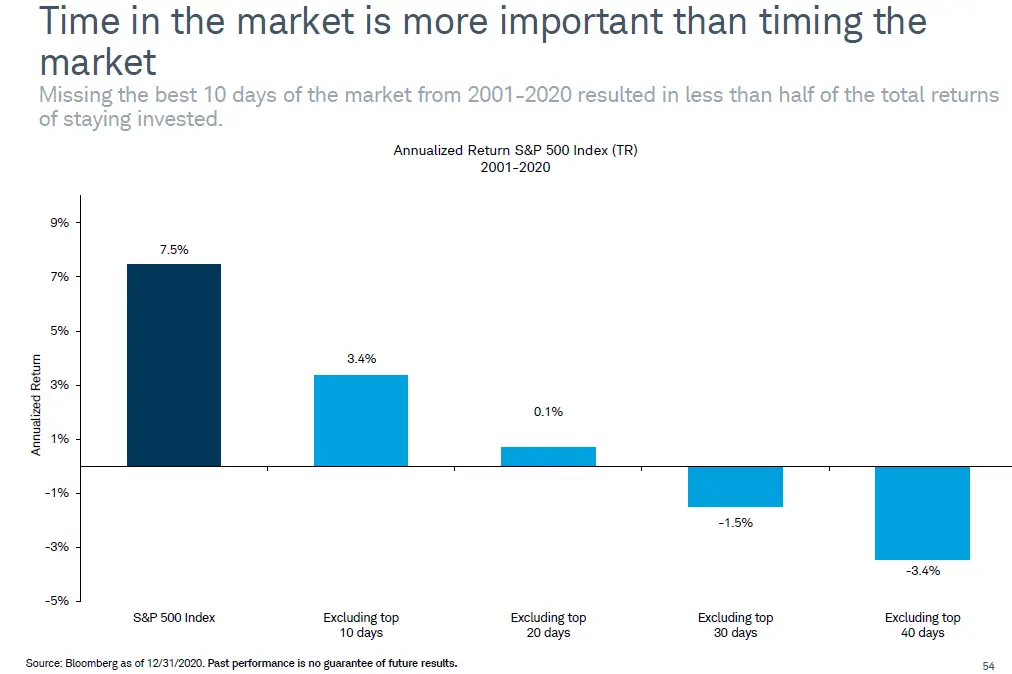

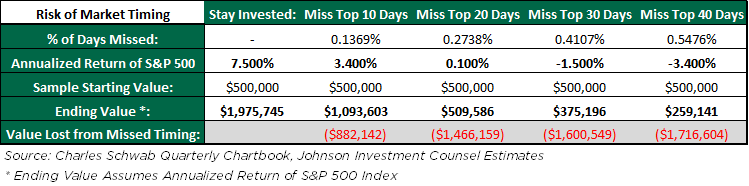

This is the most significant cost for a reason that many new investors don't realize – that the stock market's gains for any given year come from just a handful of days of stellar performance. The graph below from Schwab shows how missing out on just the 10 best days for the S&P 500 from 2001 to 2020 cut your total return in half, and the results go down from there:

Conclusion – Time In the Market Beats Timing the Market

In investigating the purported merits of market timing, we find yet another example illustrating how passive index investing beats active management on average, and of course that “time in the market beats timing the market” indeed. Trying to time the market is usually more harmful than helpful, and missing out on just a handful of days of market gains can have huge ramifications in the form of lower returns.

As always, pick an asset allocation based on your personal risk tolerance and time horizon, establish an emergency fund, invest early and often in index funds as soon as money becomes available (don't DCA), diversify broadly across asset classes and risk factors, rebalance regularly, stay the course, and ignore the short-term noise.

Interested in more Lazy Portfolios? See the full list here.

Disclaimer: While I love diving into investing-related data and playing around with backtests, this is not financial advice, investing advice, or tax advice. The information on this website is for informational, educational, and entertainment purposes only. Investment products discussed (ETFs, mutual funds, etc.) are for illustrative purposes only. It is not a research report. It is not a recommendation to buy, sell, or otherwise transact in any of the products mentioned. I always attempt to ensure the accuracy of information presented but that accuracy cannot be guaranteed. Do your own due diligence. I mention M1 Finance a lot around here. M1 does not provide investment advice, and this is not an offer or solicitation of an offer, or advice to buy or sell any security, and you are encouraged to consult your personal investment, legal, and tax advisors. Hypothetical examples used, such as historical backtests, do not reflect any specific investments, are for illustrative purposes only, and should not be considered an offer to buy or sell any products. All investing involves risk, including the risk of losing the money you invest. Past performance does not guarantee future results. Opinions are my own and do not represent those of other parties mentioned. Read my lengthier disclaimer here.

Are you nearing or in retirement? Use my link here to get a free holistic financial plan and to take advantage of 25% exclusive savings on financial planning and wealth management services from fiduciary advisors at Retirable to manage your savings, spend smarter, and navigate key decisions.

One of the issues I have with market timing: It is really easy to sell, but not so easy to know when to get back in. How much of a pullback should you wait for? 20%, 30%, 40%?

On the other hand, there are well respected analysts that use a form of market timing. Momentum is often referred to as a “factor” and moving average based systems are a little more automatic if you can stick to them, but they can underperform for years, if not decades and whipsaw you in and out of the market.

For example, Meb Faber implements a momentum market timing system based on moving averages that he claims has a backtested return of something like 18% annually. He has an ETF (GMOM) that uses the strategy, but it has a pretty high expense ratio. There are a lot of other momentum ETFs out there as well. Even Paul Merriman says he uses market timing as a way to protect against loss, but he rarely talks about it and doesn’t recommend it to his readers or listeners from what I can tell.

Indeed, gotta be right twice. Meb/Cambria had a TAA fund that did so bad, he closed it, relaunched it under a new name, and ignored the past performance. I like a lot of his writing and research, though.

John have you looked at the 12 percent solution by David Alan Carter. Basically momentum investing with etfs and bonds in a 60/40 mix or stock picking lite as you call it. Is this investing philosophy a complete waste of time and money? Backtests show much lower drawdowns and higher returns overall compared to s and p 500

Thanks

Yes, it’s a waste of time. Timing strategies are always shown to be worthless when applied out of sample in the real world. The perfect illustration of the tenet that past performance does not indicate future performance.

John,

You have put together a wonderful website. Great information and wisdom. I wish I had this info decades ago. I suffer from the same psychological issues as many…waiting for that pullback that never comes. I have listened too often to the perma-bears out there. Right now the oldest nd wisest financial gurus are saying the worst sell-off in their lifetimes is right around the corner. Poor valuations, debt, infaltion risks etc. It seems the market is always ripe for a huge sell-off, and I am to close to retirement (6-7 years) to get caught in a 50% correction. I know you are against market timing…but I feel that using a long term trending strategy would mitigate risk of a significant downturn. Using Portfolio Visualizer…a monthly 9 MA on SPY shows decent risk adjusted results. For those of us with shorter time horizons this seems reasonable. Your thoughts would be appreciated?

Portfolio Initial Balance Final Balance CAGR Stdev Best Year Worst Year Max. Drawdown Sharpe Ratio Sortino Ratio US Mkt Correlation

Moving Average Model $10,000 $184,197 11.07% 10.75% 38.05% -8.19% -15.92% 0.82 1.31 0.69

Buy & Hold Portfolio $10,000 $153,581 10.34% 14.77% 38.05% -36.81% -50.80% 0.59 0.87 0.99

Logarithmic scale Inflation adjusted

Brian

Thanks for the kind words, Brian! Technical analysis usually doesn’t really tell us anything. Without knowing your portfolio, it sounds like you just need more bonds to fit your true risk tolerance.

First – just want to say how happy I am to have found this site. I really enjoy your commentary and ideas. I was an index investor for a decade and then went active stock picking in January and it’s not gone well. I’m looking to get back to my comfort zone.

I’m currently struggling with the idea of trying to time the market. I totally appreciate what the numbers say, but it really seems different this time (…I know, I know.) All the indexes are at ATH after an almost unbroken 15 month bull run. Meanwhile, the news coming out of the US – I’m in Canada – about the delta variant and low vaccine uptake is not promising. The prospect of a 20-30% drawdown shortly after going back to index investing has me feeling quite cautious. Do you have thoughts on that? Thanks again.

Thanks for the kind words, Stephen!

I don’t worry about the short term noise. If you feel cautious, I’d say your strategy and holdings probably don’t match your true risk tolerance. You could always DCA in over a short period like 3-6 months.