This post largely originated after seeing all the misinformation surrounding dividends floating around Reddit and YouTube recently. Most users on the M1 Finance subreddit, for example, seem to be very pro-dividend, almost unwaveringly so and nearly cult-like, so I’m a little afraid to even open this can of worms for fear of being pitchforked. It’s scary how much cavalierness, misinformation, myths, and downright harmful advice in regard to dividends that I’ve seen thrown around on some of these forum posts and in YouTube videos promoting dividend investing. Moreover, most of these people seem to be doing this in taxable accounts, which makes me cringe even more. So I felt the need to illuminate some perhaps lesser known truths surrounding dividends and help people preserve their capital and returns.

Disclosure: Some of the links on this page are referral links. At no additional cost to you, if you choose to make a purchase or sign up for a service after clicking through those links, I may receive a small commission. This allows me to continue producing high-quality content on this site and pays for the occasional cup of coffee. I have first-hand experience with every product or service I recommend, and I recommend them because I genuinely believe they are useful, not because of the commission I may get. Read more here.

It makes sense, considering the nature of the M1 Finance platform renders it attractive to “dividend investors.” Also, “dividend investing” is usually the first camp that novice investors flock to when starting out, due to the countless blogs, YouTube channels, and newsletters perpetuating the strategy’s supposed benefits. This post is geared toward those novice investors who are interested in a dividend-yield-chasing strategy but perhaps don't know the information presented here.

To be clear, I am not a dividend investor. I would even say I’m anti-dividend. Yes, blasphemy, I know. Sorry to rain on the parade. Hear me out.

First, let’s define what we’re referring to here. There’s a strategy in which dividend growth – a company increasing their dividend payment over time – is used as an indicator to identify strong, stable, successful companies to invest in. There is nothing inherently wrong with this, and could even potentially allow you to beat the market (though historically dividend yield per se has actually been shown to be a suboptimal indicator of value, and is not an empirical factor that influences stock performance), as buying high-dividend-yield and dividend growth stocks incidentally gets you exposure to empirical equity factors like Value, Quality, Profitability, and lower volatility in likely-mature, conservative companies. This is actually a big part of how Warren Buffett picks stocks.

There are funds that aggregate these exact types of stocks, and they sometimes ironically have a lower dividend yield than a broad index fund. Vanguard’s VIG is the most popular one. However, recent research has shown this is still probably not the optimal approach. We’ll dive into these funds and that research more specifically later.

What I’m referring to, and what I see more often, is what are sometimes called dividend chasers – those seeking out individual high-dividend-yield stocks or funds for the sake of the dividend itself, which is usually what’s being referred to any time you see any of these words or phrases in relation to an investing strategy:

- “Income”

- “Passive income”

- “Income investing”

- “Dividend investing”

- “Living off the dividends”

- “$X per month”

For the sake of clarity, in this post I'm referring to chasing dividend yield as “dividend investing” or “dividend chasing,” and I'm referring to investing in companies that have a history of increasing their dividend over time as “dividend growth investing.” It's a subtle but important distinction, and the different terms are sometimes thrown around interchangeably, adding to the confusion.

I should also probably point out that some of the math and assessments below assume a zero-trading-fee brokerage like M1 Finance. At the time of writing, I think we're seeing the race to zero for these brokerages anyway, as others like Fidelity and Schwab are slashing fees and introducing fractional shares.

I get it. Dividend chasing as a strategy is easy to sell, and proponents are good at selling it, either sweeping the data and math under the rug, ignoring it altogether, or simply not knowing it in the first place. I can see the attraction at first glance – predictable cash payments into your account while keeping the same number of shares. Sounds great!

In fairness, I suspect most novice investors also simply don’t know some of the underlying mechanics that can make dividends per se drag down your net total return, which is what you should always be focused on. What saddens me is these same novice investors will likely read and watch most of the pro-dividend forum posts and videos and jump in without hesitation, screening for high dividend yield stocks and throwing them in their portfolios.

Here are the reasons why I don’t chase dividends, and why you shouldn’t either:

1. Dividends result in a larger tax burden.

Arguably the most important point here, but one that I think is often misunderstood and simply repeated platitudinously. If you’re holding dividend-paying assets in a taxable account, you are invariably paying more in taxes than if you were holding non-dividend-paying assets. If you are chasing dividends, you are consciously paying more in taxes than you have to.

Whether you call it a “dividend” or “withdrawal” or “income” doesn’t matter; it is a taxable event. Period. Even if your dividends are reinvested (in which case, what’s the point of chasing them?), they’re still taxed upon distribution. Thus they create a net loss in taxable accounts compared to the same securities if they didn’t pay a dividend.

Imagine selling shares of stock and immediately buying them back at the same price. You have accomplished nothing, but you’ve been taxed as a result. This is precisely how dividends work in a taxable account.

One of the pro-dividend points often raised in regard to taxation is that qualified dividends are taxed at a lower rate, which is true. Unfortunately, dividend chasers, in going after high yields, end up holding things like REITs in their taxable accounts, which distribute non-qualified dividends that are taxed at marginal income tax rates.

Moreover, even qualified dividends are taxed at capital gains rates, which is what you would pay anyway when you sell shares. Selling shares at the LTCG rate to realize only the withdrawal amount you actually need, when you need it, allows you to postpone that taxation. Also, if the amount of your withdrawal is lower than the forced periodic withdrawal of your dividends, you’ll pay less in taxes.

This is why I always try to stress that if you're aiming to maximize long-term total return, dividend-paying securities, especially high dividend payers like REITs, should not be held in a taxable account if you can avoid it. Specifically, put high dividend yield assets in a tax-advantaged retirement account where they can do no harm, turn on automatic reinvestment, and use growth stocks (growth stocks pay no or low dividends) in your taxable account.

I would also concede that a dividend income strategy is particularly attractive for many retirees who simply want to “live off the dividends” without selling shares. That's a perfectly valid approach, though allowing corporate dividend policy to dictate one's withdrawal and spending policy strikes me as odd. But again, if we're talking about a taxable account, the better strategy is to buy dividend stocks at that point at which you're ready to use the dividend payments as regular income. Until then, they're just a tax drag. The same argument would apply to the yield from bonds, which the retiree is likely also holding.

2. Dividends are not “free money.”

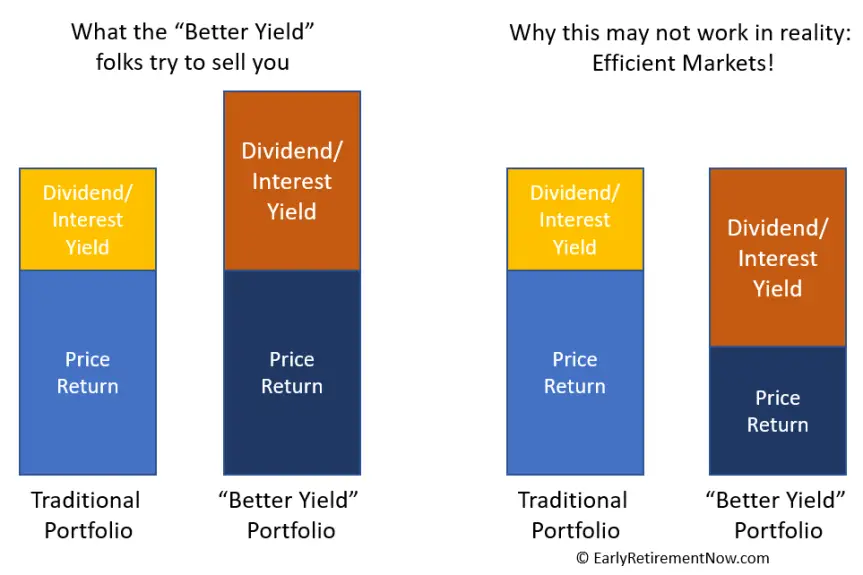

A company’s or fund’s dividend has already been intrinsically factored into its value and subsequently, its share price. That is, it has already been “priced in.” Markets are reasonably efficient. You are not gaining anything extra by receiving a dividend. $1 is $1 is $1; there is no free lunch in the market.

For a simplistic, hypothetical example, let’s say you own Company ABC and you transfer $1 from its company bank account to your personal bank account. Your net worth has not increased as a result; you own the company, so you owned that $1 the whole time. You’ve just subtracted it from somewhere – in this case the company’s value – and added it somewhere else – your pocket.

Similarly, your partial ownership of a different company (in the form of shares) may be worth $1 that the company holds. Upon transferring it to you in the form of a dividend, you are no wealthier as a result, as the company’s value has just decreased by the amount of its dividend payment. Specifically, with the dividend, you own more shares at a lower price. Without the dividend, you own fewer shares at a higher price. They are identical. Here’s a graphical summary of this concept:

Essentially, you are being paid with your own money. This concept is similar to how some people get excited about receiving a tax refund each year. It was your money all along.

Note that this is not saying that dividends are not important as a return of value to the shareholder. They comprise a significant portion of investor returns in some cases (more on this in a second). The important distinction is that a company's dividend policy is irrelevant to the valuation of shares after you account for its investment policy.

Here's an example to illustrate.

A firm with no debt wants to finance a project, but it also still wants to use their cash on hand to pay a dividend to shareholders. After paying the dividend, the company must then issue new shares to finance the project. So existing investors are compensated for their now-diluted shares. New shares are issued at the lower price equal to the previous share value minus the dividend payment. Now the firm has cash again to finance their project, and everyone's happy. But the company now has more shares outstanding at a lower average share price.

Had the company not wanted to issue new shares, they would have to finance the project from their liquid cash, so no dividend this time, but existing shareholders have the same claim on future profits as their share value is unchanged.

The only difference between these two cases is how the returns are distributed to the investor. In that sense, dividend policy is just a financing decision.

In short, a company has profitability and investment policy, which tells us the quality of the company and why we're investing in it in the first place (hint: factors). After we account for those things, the subsequent dividend policy is irrelevant to the valuation of shares.

3. Dividends limit total returns.

Because of the nature of #2 above, you are effectively withdrawing money from your account each time a dividend is distributed. If they are not reinvested, you have now taken out capital that could have been left in to appreciate more, ultimately actually lowering your total returns. That is, those dividends are missing out on the compounding. This is another hugely important distinction in considering whether or not to reinvest dividends.

For a simplistic, theoretical, ad hoc example, if you bought 1 share of Company A at $100 and it increases by 10% to $110, your unrealized return is 10%. Company A does not pay a dividend. Let’s suppose you also have 1 share of Company B, which also has a share price of $100, and that Company B just paid you a $1 dividend that you chose not to reinvest but take as income. Company B also grew by 10%. Company B’s share price is now $99, which has now grown by 10% to $108.90. Adding in your $1 dividend distribution you took equals $109.90, for a total return of 9.9%. Your initial investment capital is the same in both examples, yet your total return on Company B is lower than Company A.

Disregarding taxation, we could even simplify that example and exclude the 10% growth aspect to show that $100 in Company A = $99 in Company B + $1 dividend, meaning the dividend puts you right back where you started. At scale, in the market as a whole, this is all usually happening somewhat invisibly behind the scenes, but rest assured it is happening1. Again, $1 is $1 is $1.

Had you put $10,000 in an S&P 500 index fund in 1985 and let it sit for 34 years through 2018 without adding anything and reinvested the dividends, you would have ended up with $314,933 for a total return of 3049%, an effective CAGR of 10.68%. Without reinvesting dividends, you would have ended up with capital appreciation of $118,556 and dividend payments of $37,394 for a total of $155,950 and a total return of 1460%, an effective CAGR of 8.41%. That’s less than half the return!

As another simplistic, somewhat extreme but very telling example, “A Single Share of Coca-Cola Bought for $40 in the 1919 IPO With Dividends Reinvested Is Now Worth $9,800,000 vs $341,545 Without Dividends Reinvested.”2

These examples still do not even factor in the tax on the dividends you took as income. Pre-tax returns of dividend-paying and non-dividend-paying stocks are indentical (which is why dividends are harmless in a retirement account if reinvested), but taxation invariably, unequivocally results in a lower total return for the dividend investor in a taxable account.

Compound these issues across many stocks with much more money over many years and you can see the huge problem this creates. We’ll illustrate this specific problem with some more realistic examples later.

4. Dividends are a forced withdrawal.

Extending #3 above, dividends are simply a withdrawal forced upon you by the very company you’re invested in. If you’re truly investing with a long time horizon, chances are you don’t need the dividend distribution as income monthly, quarterly, or even annually. Even if you did, you could simply withdraw what and when you wanted as discussed above.

Instead, dividend distributions force you to withdraw money at regular intervals regardless of whether or not you want to. This can be particularly problematic if you are purposely trying to keep your taxable income low in a specific year.

The market tends to go up more than it goes down. That's the whole reason we're investing in it in the first place. Because of this, selling shares as needed is mathematically preferable to using dividends as income, because it allows more money to stay invested longer. While the difference may be marginal, on average this will result in higher returns over the long term. This is the same principle that explains why dollar cost averaging is suboptimal, and is also why market timing tends to fail.

5. I don’t want dividends.

With a company’s earnings, they can choose to pay for things like R&D, future projects for growth, and mergers and acquisitions. If they are in a position in which they can do none of those things, they can return value to shareholders via dividends or stock buybacks. On average, all these things achieve the same net result for shareholders.

If I’m invested in Company A, the dividend is the last outcome I want out of the aforementioned options. After all, I’m invested in Company A because I think it will grow! Warren Buffett, arguably the most respected investor in history, feels the same way, which is why Berkshire Hathaway doesn’t pay a dividend3.

I would also argue that share repurchases are slightly better than dividends anyway, given that you’re essentially taxed twice on dividends since the company [hopefully] had to pay corporate income taxes on that cash.

6. Dividends only possess a psychological benefit.

This is the reason why I think dividend chasing intuitively seems attractive at first glance and why many people illusively buy into it as a strategy. It simply feels good to have cash show up in your account regularly and predictably. This part I understand somewhat.

Hersh Shefrin and Meir Statman actually looked into the phenomenon of dividend preference in 1984. They found 2 main reasons why some investors chase dividend yield: 1) those investors recognize they are unable to delay gratification and adopt a “cash flow” approach to pay for regular expenses, and 2) the psychological principle of loss aversion causes investors to prefer the feeling of receiving a dividend over “losing” shares in order to realize capital gains of an equal amount4.

I try to stay pragmatic and scientific with my investing and leave emotions out as much as I can. If for some reason the mental accounting fallacy of dividend chasing keeps an investor more disciplined or lets them sleep better at night than selling shares in a buy-and-hold strategy would, then I guess I’d have to support it. I would rather see someone chase dividend stocks than penny stocks.

7. Dividend chasing decreases diversification.

By solely chasing dividend stocks, you’re missing out on roughly 60% of the US market, thereby posing a concentration risk and resulting in a lack of diversification. This also means you’re missing out on the potential outperformance of that 60%, which is of some significance considering Growth has crushed Value over the past decade. Apple, Amazon, Facebook, and Visa are just a few well-performing Growth stocks that you would have missed out on. Moreover, most dividend income investors are doing so with large-cap dividend stocks, which means they're also missing out on small- and mid-caps, which have outperformed large-caps historically.

Second, there is no sound evidence that dividend-paying stocks are any better – in terms of total return – than non-dividend-paying stocks. Remember, the dividend itself does not account for a stock’s performance.

Lastly, we know that picking individual stocks is extremely unlikely to outperform a broad market index over a time horizon of 30+ years anyway.

8. Dividends are not guaranteed.

Dividend investors usually like to claim that their predictable dividend payments will still be there during market turmoil. This is not necessarily true. Companies can decrease or eliminate their dividend payment at will5.

Even worse, companies will sometimes borrow in order to pay their dividends so as to not spook shareholders by decreasing or eliminating the dividend, in which case you effectively just borrowed with interest to pay yourself your own money.

Of course, Merton Miller and Franco Modigliani figured all this out in 1961, so it’s frustrating to see the myths of dividend chasing and “income investing” persist1,6. Again, I suppose since it’s an active strategy, it’s easier for people to create blogs and YouTube videos and newsletters around it and make money providing information to people who are new to investing or who may not know any better. It’s also a lot more exciting than saying “Buy VTI and don’t touch it for 30 years.”

So now let’s circle back to our first “type” – “dividend growth” investing – and look at some specific funds. Again, note that I am in no way against this strategy of investing in stocks with a history of increasing their dividend over time (“dividend growth“). It may allow you to beat the market in the long run.

VIG is probably the most popular of this type, and rightfully so. It “seeks to track the performance of the NASDAQ US Dividend Achievers Select Index (formerly known as the Dividend Achievers Select Index).” So it focuses on large-cap blend stocks with a history of dividend growth (increasing their dividend payment over time). There’s also an international version, VIGI.

Dividend chasers seem to like VYM due to its yield. It “seeks to track the performance of the FTSE® High Dividend Yield Index, which measures the investment return of common stocks of companies characterized by high dividend yields.” So here we’re looking at large-cap value stocks that happen to have a high dividend yield, not necessarily an increasing dividend over time. I think because of that fact, because Growth has outperformed Value in recent years, and because tech has performed well in recent years, VIG has crushed VYM recently. Granted, because VIG is looking at dividend growth and VYM is looking at the dividend yield per se, these funds aren’t really the same thing. I wrote a detailed comparison of these 2 funds here.

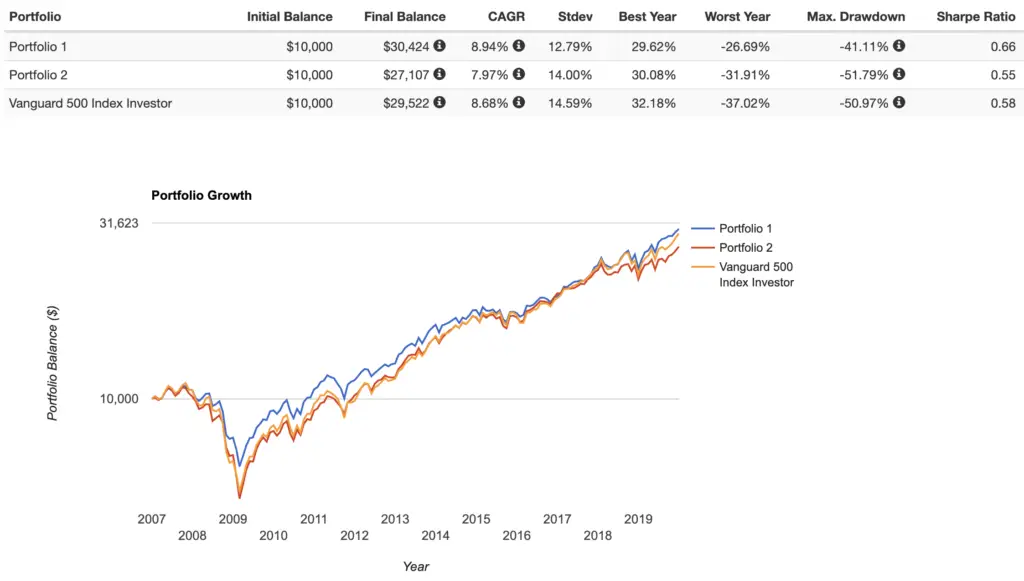

Even with dividends reinvested, through 2019, VIG would have given you an extra CAGR of 1.33% compared to VYM since VYM’s inception in late 2006 (illustrated below; VIG is the blue line, VYM is the red line). VYM also lagged the S&P, while VIG beat it and had a higher Sharpe ratio, better max drawdown and Worst Year figures, and less volatility. Interestingly too, VIG fared much better than both VYM and the S&P through the 2008 crisis and the recent Q4 2018 correction.

Despite offering these funds, Vanguard themselves investigated the strategies contained in VYM and VIG and concluded, as I pointed out earlier, that the stocks’ performance was fully explained by exposure to equity factors like Value, Quality, and lower volatility. Specifically, the returns of high-dividend-yield equities are explained by the factors of Value and low volatility, and the returns of dividend growth equities are explained by Quality and low volatility7. This is not a bad thing, just something to note – that the dividend payment itself is not responsible for the [out]performance of VIG compared to the S&P 500. Again, VIG may allow you to beat the market in the long run.

SCHD is another popular fund like VYM. Both have lagged the S&P since SCHD’s inception in 2011. This makes some sense when we look at the valuation metrics of these types of funds. Since the 2008 crisis, many investors have flocked to low-volatility funds to the point where the strategy has been “cursed by popularity.” The valuation metrics (source) for these are now higher than their “normal” Value ETF counterparts and the S&P 500 index, indicating lower expected future returns for these low-volatility funds.

DGRO from iShares should perform similarly to VIG, with slightly more volatility since it’s more inclusive with its 5-year-growth requirement instead of VIG’s 10-year. As a result, DGRO should have more exposure to comparatively smaller companies than those in VIG. Maybe slightly more reward for slightly more risk. It will be interesting to see going forward. Here’s a comparison of those. Nearly identical, with a tiny bit more volatility, though interestingly VIG had a worse max drawdown during the Q4 2018 correction. Unfortunately DGRO has only been around since 2014.

NOBL from ProShares claimes to be the “only ETF focusing exclusively on the S&P 500 Dividend Aristocrats—high-quality companies that have not just paid dividends but grown them for at least 25 consecutive years, with most doing so for 40 years or more.” Its ER of 0.35% is much higher than VIG’s 0.06%. Like DGRO, NOBL may slightly outperform VIG over the long run, albeit with more volatility. Here’s a backtest comparing NOBL and VIG since NOBL’s inception in late 2013, using the S&P 500 as a benchmark. The S&P has actually slightly outperformed NOBL since then, though again the dividend appreciation ETF’s fared better through the Q4 2018 correction with smaller drawdowns.

I did run some of the other popular players in this space – SDY, SPLV, SPHD, DVY, etc. – but they were all very similar and I think VIG beat them on all performance metrics and has the highest AUM by far, so I’m sort of holding VIG as the gold standard in that category of dividend-oriented ETF’s. Though note that these others should have lower valuation metrics than VIG precisely because people are flocking to VIG.

A lot of people have also been raving about QYLD, a covered call fund with a huge dividend. I'm not a fan.

For me, a dividend-oriented portfolio, made with a pie for M1 Finance, might look something like this.

But since we now know that dividend investing is essentially just a Value tilt and since the high-dividend low-volatility strategy is being “cursed by popularity,” you may be better off just investing in large-cap Value8. I compared some large cap value funds here. Moreover, we know that dividends per se are not responsible for a stock's performance, and that they are a suboptimal proxy for accessing known equity factors like Value and Profitability. The Dividend Aristocrats (NOBL), for example, have outperformed the market historically not because of their dividend payments, but because of their possessing excess exposure to these factors that tend to pay a premium.

Thankfully – and somewhat ironically – dividend growth investing (NOBL, VIG, DGRO, etc.) sort of “accidentally” gets you some exposure to those factors, but I would argue buying dividend stocks is still a suboptimal way to access those factor premia. This somewhat “accidental,” partial exposure to the factors comes at the cost of less diversification.

The problem with focusing on dividend stocks is that not all dividend stocks have exposure to the equity factors, and not all stocks with exposure to the factors pay dividends. Until recently, dividend growth investing was admittedly perhaps the best way for retail investors to access that exposure (at least for Value and Quality) historically, but now we're seeing products that directly target those factors, e.g. VLUE, QVAL, QUAL, AVUV, etc. I explored the best Value funds across various geographies and cap sizes in a separate post here.

Interestingly, Fama and French actually used Miller's and Modigliani's mathematical illustrations of dividend policy irrelevance to the valuation of shares (from their 1961 paper) in their construction of the 5 Factor Model. We know this “worked” because we don't observe unexplained alphas when applying the 5 Factor Model to dividend portfolios.

After spending much time researching the subject, Meb Faber succinctly summarizes some of these points as follows here:

- Dividend yield investing is rooted in value investing.

- Historically, focusing on dividend yields rather than value, has been a suboptimal way to express Value.

- If you have to focus on dividends, you MUST include a valuation screen or process to avoid high yielding but expensive, junky stocks.

- The hunt for yield has caused dividend stocks to reach valuations levels never seen before relative to the overall market.

- Since dividend stocks are currently expensive, we prefer a shareholder yield approach combined with a value composite screen.

- Once you have a preferred value methodology, AVOIDING dividend stocks in the strategy could result in additional post tax alpha of approximately 0.3% to 4.5% for taxable investors.

He shows in following table (source) that investing in Value and avoiding high dividend payers (far right column) came out ahead in all taxable environments. EW stands for “equal weight.”

If anyone knows of any large-cap value ETF’s or mutual funds that consciously avoid high dividend payers, let me know.

TL;DR: If you’re set on dividend orientation, I would say feel free to utilize dividend growth/appreciation stocks and ETF’s like these as a small tilt, but please stop chasing dividends for the sake of the dividend itself, especially in a taxable account.

Specifically, hold anything with regular distributions – dividend stocks, REITs, bonds, etc. – in a tax-advantaged retirement account and reinvest the dividends. Hold Growth stocks that do not pay a dividend in taxable accounts and sell shares as needed for any “income.”

Here’s some additional reading material on the subject if you’re interested:

- Swedroe: Dividend Growth Demystified

- Buffett: You Want a Dividend? Go Make Your Own

- The Yield Illusion: How Can a High-Dividend Portfolio Exacerbate Sequence Risk?

- Swedroe: Vanguard Debunks Dividend Myth

- Investing Lesson 11: The Road to Riches Isn't Paved with Dividends

- Dividend Investing: A Value Tilt in Disguise?

- The Mystery Behind Dividend Yield Investing

- Using Factor Analysis to Explain the Performance of Dividend Strategies

- Swedroe: Why Chasing Yield Fails

- Why Chasing Dividends is a Mistake

- Swedroe: Mutual Funds Lace Portfolios With Dividend ‘Juice’

- Don’t buy into the dividend ‘fallacy,’ new academic paper warns

- Swedroe: Irrelevance Of Dividends

- The Dividend Disconnect

- The Dividend Puzzle

- Dividend Stocks are the Worst

- How Much Are Those Dividends Costing You?

- What You Don’t Want to Hear About Dividend Stocks

- Slaughtering the High-Dividend Sacred Cow

Are you nearing or in retirement? Use my link here to get a free holistic financial plan and to take advantage of 25% exclusive savings on financial planning and wealth management services from fiduciary advisors at Retirable to manage your savings, spend smarter, and navigate key decisions.

References

- 1.Miller MH, Modigliani F. Dividend Policy, Growth, and the Valuation of Shares. J BUS. January 1961:411. doi:10.1086/294442

- 2.Kennon J. Reinvesting Dividends vs. Not Reinvesting Dividends: A 50-Year Case Study of Coca-Cola Stock. Joshua Kennon’s Personal Blog. https://www.joshuakennon.com/reinvesting-dividends-versus-not-reinvesting-dividends-coca-cola/.

- 3.Investopedia. Why Doesn’t Berkshire Hathaway Pay a Dividend? Investopedia. https://www.investopedia.com/ask/answers/021615/why-doesnt-berkshire-hathaway-pay-dividend.asp.

- 4.Shefrin HM, Statman M. Explaining investor preference for cash dividends. Journal of Financial Economics. June 1984:253-282. doi:10.1016/0304-405x(84)90025-4

- 5.O’Brien S. The Biggest Dividend Stock Collapses of All Time. Dividend.com. https://www.dividend.com/dividend-education/the-biggest-dividend-stock-disasters-of-all-time/. Published December 11, 2014.

- 6.HARTZMARK SM, SOLOMON DH. The Dividend Disconnect. The Journal of Finance. June 2019:2153-2199. doi:10.1111/jofi.12785

- 7.Schlanger T, Kesidis S. An analysis of dividend-oriented equity strategies. Vanguard. https://www.vanguardinvestments.dk/documents/dividend-oriented-equity-strategies-uk-eu.pdf. Published May 2017.

- 8.Faber M. How Much Are Those Dividends Costing You? Meb Faber Research. https://mebfaber.com/2016/05/02/much-dividends-costing/. Published May 2, 2016.

Disclaimer: While I love diving into investing-related data and playing around with backtests, this is not financial advice, investing advice, or tax advice. The information on this website is for informational, educational, and entertainment purposes only. Investment products discussed (ETFs, mutual funds, etc.) are for illustrative purposes only. It is not a research report. It is not a recommendation to buy, sell, or otherwise transact in any of the products mentioned. I always attempt to ensure the accuracy of information presented but that accuracy cannot be guaranteed. Do your own due diligence. I mention M1 Finance a lot around here. M1 does not provide investment advice, and this is not an offer or solicitation of an offer, or advice to buy or sell any security, and you are encouraged to consult your personal investment, legal, and tax advisors. Hypothetical examples used, such as historical backtests, do not reflect any specific investments, are for illustrative purposes only, and should not be considered an offer to buy or sell any products. All investing involves risk, including the risk of losing the money you invest. Past performance does not guarantee future results. Opinions are my own and do not represent those of other parties mentioned. Read my lengthier disclaimer here.

Are you nearing or in retirement? Use my link here to get a free holistic financial plan and to take advantage of 25% exclusive savings on financial planning and wealth management services from fiduciary advisors at Retirable to manage your savings, spend smarter, and navigate key decisions.

I appreciate the points but for me its about cash flow. I want to generate a minimum passive income for FIRE and deliberately hold stocks that pay a good sustainable dividend. I don’t want to rely on PE expansion that is currently a product of the SPX.

I don’t chase the highest yielding stocks that are all but guaranteed to decrease in value before cutting the divs.

Great Article! I am looking for some mid and small cap low or non-dividend companies.

What would be the easiest way to find them?

Best bet would just be Growth funds for whatever cap sizes you’re targeting.

Ah, the age old question, to dividend or not to dividend. I have very much enjoyed reading through your articles and portfolio designs. I just found this site last week. You have a very analytical way of looking at things and seem fairly unbiased and recognize bias which is excellent. I especially like the write up on the Hegfundie portfolio. It’s fascinating!

I don’t think dividends are black and white, good or bad. Depends on the individual, the company, the fund, and especially the individual’s mental temperament. If your goal is total return, then yield chasing is statistically unwise. Holding BDCs, MLPs and REITs in a taxable account makes no sense unless you are getting these businesses at such a huge discounted value to offset the risk and tax bill. I don’t know how smart people are in general but I’d say 1% of 1% of people understand these business structures well enough to play in that arena. Funds like QYLD feel like a Ponzi scheme or like getting on heroine. Great in the moment unhealthy in the long run.

I am not terrified of dividends, and appreciate them as an owner of a company if share prices are too high for repurchase and capital cannot be reinvested with good enough returns. And, as long as the payout ratio is healthy. Taking on debt to maintain a fat dividend is just bad business.

The current FIRE movement fad is concerning. Yield chasing is like choosing a really sick and diseased chicken that sometimes lays big eggs over a chicken that is very healthy and regularly lays smaller eggs. …it’s the only analogie I could think of. Why wouldn’t you want a business that can reinvest capital at high rates of return at a discounted price tag?

At the end of the day, the things I know to be true for me are: The future is unknowable, spend less than you make, know what you’re buying, have a clear and definitive goal to work towards, acknowledge what you don’t know, always keep learning and just be kind to people.

Thanks again! Love and appreciate the articles and will continue to read.

Thanks for the thoughtful comment and for the kind words!

I do not understand why in so many articles it is mentioned about Warren Buffet and his company that does not pay out dividends. We are not Warren Buffets and neither is the writer. Moreover, Buffet’s company may not pay out dividends, his company is very eager to EARN dividends. Have you seen lately how many dividend companies are in his portfolio? Don’t tell me that MR Buffet doesn’t like dividends, please!

Us not being Warren Buffett has nothing to do with the irrelevance of dividends per se or him not liking them, which, once again, he has said repeatedly. Go ask him. He does like profitable companies – mostly Value stocks – that are able to pay them; he was a factor investor before factors were a thing.

John, I keep returning to this post for insights, great job!

I think the value of dividends could be in the stability of their rate over time v market performance and price which vary significantly. In terms of a large cap ETF that leans toward quality, SCHD might bear a look.

Thanks, Greg!

Wouldn’t a dividend strategy beat a growth strategy if one reinvested accumulated dividends by “buying on dips” (at below avg cost) and thereby accumulating shares at a lower avg cost?

But yes, you’re right tax drag would negate any minor gains.

No

Good article!

Other quotes you often see:

– “I don’t care if my stock goes down in price. Actually, I like when the price goes down because then my yield goes up!”

– “Unrealized gains and losses don’t matter because I’m not selling anything.”

– “If I have to sell shares then that reduces my ability to make money in the future, but if I get dividends, then I get to keep all of my shares.”

The most insidious part of the dividend fallacy is the presumption that dividend yield is the minimum return someone will make on their investment. Dividend cultists see that 5% yield on a stock and jump on it thinking they can’t lose.

It’s overwhelming how quickly this passive income/dividend cult theory has spread.

Wanted to ask if you have an article on the difference between Spider, Global X, Fidelity, Vanguard etc.

It seems like most recommendations are Vanguard only

I don’t. Vanguard funds usually have the lowest fees and greatest liquidity. Fidelity does have cheaper sector ETFs currently. I did a post on them.

Great stuff and thank you for it! Can you comment on the argument that a strategy of selling stocks to generate income needed after retirement may force you to sell your stocks are down? Stocks are volatile and timing of sale to pay the bills may be suboptimal. . Whereas the dividend cash flow is likely to be less volatile and less subject to suboptimal timing.

Thanks, Steve. Same outcome in terms of share value (and subsequent portfolio value). Just mental accounting. A constant withdrawal rate in retirement doesn’t make much sense anyway, as I touched on here.

Nice article and makes sense for younger investors; unless you are retired and depend on income. Assuming holding investments in an IRA account so taxes are moot.

The SP500 capital appreciation has been good for retirees providing a substantial income (by selling shares) and still have growth. This is all fine until a prolong correction takes place; why a dividend income etf maybe more desirable. Trick is looking for a dividend income etf that has capital appreciation as well as providing income. Jepi and Schd come to mind with a sprinkle of Qyld to boost yields. I would still hold cash so when a substantial correction takes place, invest back into something like Fzrox. So still maintain multiple fund portfolio like fzrox, fzilx, and dividend etf (in lieu of bond etf).

Wish more readings are available for retirees that are straight forward and meaninful. I like your approach that points out the good and bad without trying to sell something or make money off of you. Thanks again.

Thanks for the comment, Ross. The message doesn’t change for retirees. As I noted, thinking that using dividends for income is superior to selling shares of an equal amount is just a mental accounting fallacy. Granted, it’s one that usually makes the investor feel better emotionally, which can certainly be of value – no pun intended – if it helps the retiree stay the course. But your examples ignore the very real possibility of dividends being cut or suspended during downturns or bear markets. Moreover, there have been periods of market turmoil when Value stocks fell further than Growth stocks. Regarding QYLD, I explained in detail here why I think it’s pretty awful. I just did a post on ETFs for retirement here.

While it’s true that dividends may be cut during some down markets, doesn’t it depend on what’s driving that down market?

For example, if a 15% correction happens in Q1 2022 and it is driven mostly by higher interest rates (negatively impacting DCF valuations) and higher bond yields (moving capital away from stocks toward bonds), and not by lower earnings, wouldn’t dividends be mostly safe from cuts?

Sometimes. Largely just comes down to the impact on corporate earnings and cash flow.

I know this is old, but Wade Pfau made the same comment: “…thinking that using dividends for income is superior to selling shares of an equal amount is just a mental accounting fallacy.”

The issue I have with this idea is not considering the TIME element and company growth: If you SELL shares to make “X dollars”, you have fewer of those shares to sell later, and eventually your portfolio of shares goes to 0. Whereas with a dividend payout, you keep your entire portfolio of shares.

I’m guessing that the portfolio of decreasing shares has increasing value even as you decrease the holdings, where the portfolio that maintains its shares has … pretty much the same value (or better?) because the company **should be able to maintain growth**?

Taking a snapshot in time for the “accounting” trick vs including the time element seems to be missing something. What am I missing?

Still just mental accounting, Jim. Number of shares per se is irrelevant; we’re concerned with the value thereof.

You seem to be extremely knowledgeable about M1 Finance. I’ve been considering an account but have had a hard time getting information without actually opening an account which I don’t want to do. I’ve tried calling but all I’ve achieved with that is endless hold music. I have never gotten anyone on the end of the line.

So let me ask you a question relevant to this article (which, by the way, I really enjoyed and appreciated). If I want to set up an M1 portfolio for income purposes, can it be set up to return an automatic monthly pay out, either a percentage of the capital value or a fixed amount? What I’m thinking of is setting a withdrawal amount, if there’s sufficient cash (from distributions), the income is paid out of that and the remaining income added to the rebalanced portfolio. If there isn’t sufficient cash enough is added to the cash at rebalance to provide the target income.

Seems straightforward, but is there a natural way for the system to handle this?

Appreciate anything you can add to help.

Yep! You can set up automatic recurring transfers of a specific amount on a calendar, or if you have a premium account option you can set up some more complicated algorithmic “Smart Transfers” based on dollar thresholds.

As an aside, you can also ask questions on the M1 Finance subreddit here and usually get answers very quickly. They also have some pretty good Support pages here.

Hi I was wondering if investing in small cap dividend payers would be more profitable than the blue chip stocks, especially since there’s a higher dividend yield?

Stocks like:

Frontline Ltd. (FRO) 2.00 USD (A) Div. Yield: 23.041

Annaly Capital Management Inc. (NLY) 0.22 USD (Q) Div. Yield: 9.534

Kimbell Royalty Partners Representing Limited Partner Interests (KRP) 0.27 USD (Q) Div. Yield: 8.213

With small cap dividend payers I thought that they had a good opportunity for growth as well as being able to make some money on the side.

I’m planning to go into the navy and I figured since I couldn’t day trade like I used to I would invest and diversify dividend stocks in my portfolio because I didn’t want to actively manage them. Also would it be a good idea to buy dividend stocks in a RRSP? in the case of Frontline Ltd. (FRO), you’d be making your money back on dividends in around 5 years, and with me being so young I figured that was a great investment.

Sounds like you may have missed the entire message of this article – that dividends aren’t free money and that stocks should not be preferable based on their dividend payment. If you mean small cap value stocks as a whole, yes I’m a fan.

None ETFs like Vanguard charge fees, ETFs charge tax, I see nothing wrong with reinvesting dividends when you plan on doing so long-term. In my opinion it’s like compound interest and can outweigh taxation in the end. But that’s just me and my own personal experience in the market.

But that’s the entire point – that “compound interest” is not free money and is still subject to taxation regardless of whether or not it is reinvested, and is thus not ideal for a taxable environment. Granted, it’s usually impossible to avoid a dividend; index funds like VOO still pay one.

I love this. Which book?

Not sure what you’re asking.

I never comment but this was a really good article and must have taken a LONG time to put together so thank you.

The HEDGEFUNDIE article is also super interesting. Its amazing how many millions of article there are about portfolio allocation when in the end from what I have learned the best approach is just buy VTI, VUXS and BND in an allocation that works for your risk profile and just stick with it over time. It will beat out the vast majority of everything else.

Thanks for the kind words! Glad you liked it.

Indeed! I still like to tinker a bit by adding a modest amount of leverage based on the idea of Lifecycle Investing – investing while young and deleveraging as I get older to diversify across time – as well as utilizing minor factor tilts based on the research for greater expected returns and more importantly, lower risk and narrower distribution of outcomes. But it’s all still rooted in broad index investing.

John:

I read your advise all the time. I like your thinking. You have helped us with our investing more than any other source. This dividend article is a great example of common sense. Thanks for pointing out the obvious!

I am a Bogle follower also and believe in Vanguard funds/etf.

Jeff

Jeff, wow, thanks for the kind words! Really glad you’ve found the content useful!

Thank you for an illuminating article.I am 73 yrs old and don’t need monthly income or withdrawal.I am paying too much in taxes from Dividends and Capital gains in Taxable accounts.How to get out of these into index ETF’s without incurring huge tax bill?Also Vanguard allows to swap index funds to ETF’s but is there any advantage doing that?

Hi Aruna, I’d say talk to a CPA and/or CFP about the tax implications. There are nuances in retirement so it would depend largely on the account type and your tax bracket. ETF’s are index funds. You might mean swapping mutual funds to ETF’s. They’re very similar, so probably no reason to switch.

Great article, I am a new investor and trying to learn as much as possible. I I was going to start my M1 portfolio with VIG, but now I am having seconds thoughts since it will be held in a taxable account.. Would VOO be a better choice, if not what would you recommend for my first ETF investment?

Thanks Jimmy. I think VOO and VTI are both great choices for a broad market index fund. VTI gets you some exposure to small- and mid-caps, which have outperformed large caps historically, whereas VOO is all large caps via the S&P 500 index. I also like VWO for some international exposure to Emerging Markets.

What about holding Master Limited Partnerships in your Taxable account?

Hey Michael. Distributions from MLP’s do get preferential tax treatment; they deduct from your cost basis. The tradeoff is that MLP’s generate the dreaded K-1 form which is a headache at tax time.

Thank brother! Do you have a recommended MLP? I would like to own one. I wouldn’t want to deal with multiple K1s. One is enough for me!

I don’t; I don’t do any stock picking anymore. I’d probably just buy an energy ETF like VDE and call it a day.

Thanks for the advice! I’m not into the stock picking. I’m long term, buy and hold forever. I’ll check those out. ✌????

Is it possible to sell shares in a taxable account and transfer it to a retirement account on M1? If so, how long does it take?

I think you’d have to withdraw to cash first and then deposit into the retirement account. Email M1 Support.

so on a taxable account (so there is liquidity to buy a home or whatever) its better to get like a total stock market fund so that it has little to no dividends and is only appreciating. then i just sell shares when i need money. Is this correct?

I don’t get the point of a dividend then. It’s like a smokescreen because it doesn’t make you more money but it does increase your tax bill

Hi Joe,

Yes, selling shares should be preferable if you’re not using that money every month. The most tax-efficient approach would be to hold Value stocks in tax-advantaged space and Growth stocks in taxable. Obviously a total market index is less cumbersome.

A dividend is just a periodic, forced return of value to shareholders from companies who can’t or choose not to invest that money back in the company for growth.

I know this is kinda an old thread. Usually dividend etfs have lower volatility. What if I need the money immediately?

Wouldn’t I be forced to sell at a loss if the market is down?

Value stocks have been more volatile than Growth stocks historically. Again, a dividend is effectively just a tiny “forced to sell.”

But what if you want to live off dividends?

Totally fine! But selling shares should be preferable if you don’t absolutely need that money every month. As I noted, it also doesn’t really make much sense to consciously incur the tax drag in a taxable account if you’re in an accumulation/growth phase before retirement.

>But selling shares would be preferable

Unless the market crashed by 80% and stayed down for a decade, and you’re forced to sell at a loss to produce income.

Still the same thing as receiving dividends during that time, plus you get to harvest losses.