Financially reviewed by Patrick Flood, CFA.

Sequence of return risk may very well ruin your financial retirement plans, and all from sheer bad luck. Here we’ll look at the nature and implications of sequence of return risk in retirement, and some proposed solutions to at least mitigate its potential negative impact.

Disclosure: Some of the links on this page are referral links. At no additional cost to you, if you choose to make a purchase or sign up for a service after clicking through those links, I may receive a small commission. This allows me to continue producing high-quality content on this site and pays for the occasional cup of coffee. I have first-hand experience with every product or service I recommend, and I recommend them because I genuinely believe they are useful, not because of the commission I may get. Read more here.

Contents

What Is Sequence of Return Risk?

Sequence of return refers to the variability of year-to-year market returns. The “risk” thereof specifically refers to how the timing of withdrawals during retirement can negatively impact the value and viability of the portfolio going forward.

At retirement, you are likely no longer making contributions and are instead withdrawing money each year. Since these withdrawals don’t get replenished by new contributions, the sequence of your returns matters. Withdrawals hurt the future portfolio value more in bear markets and less during bull markets, as you are withdrawing proportionally more during the former and proportionally less during the latter. The combination of withdrawing and poor portfolio performance may deplete it so much that you later exhaust the retirement savings that are left.

Markets are largely unpredictable. The expected average annualized return of your investment portfolio is not going to happen every single year. The long-term averaging out or “self correcting” of the stock market doesn’t help over a short period like 5 to 10 years, during which sequence of return risk may ruin the rest of your retirement. In short, if you get a “bad sequence” of returns at the beginning of your retirement, you may run out of money later, and your planned safe withdrawal rate is no longer safe.

Since all crystal balls are cloudy, the type of sequence you get is unfortunately simply a matter of luck. Maybe the best examples of getting the bad luck of a “bad sequence” would be someone entering retirement in 2000 at the height of the Dotcom Bubble or in 2008 at the start of the Global Financial Crisis.

The famous “4% rule” as a safe withdrawal rate estimate for retirement planning was born of this sequence risk.

The Potential Upside of Sequence Risk

It's not all bad news, though. On the flip side, starting retirement with a “good sequence” of returns means you’ll have more money – in fact, much more – than you expected later in retirement, allowing you to sail along unscathed and worry-free and providing the ability to spend more.

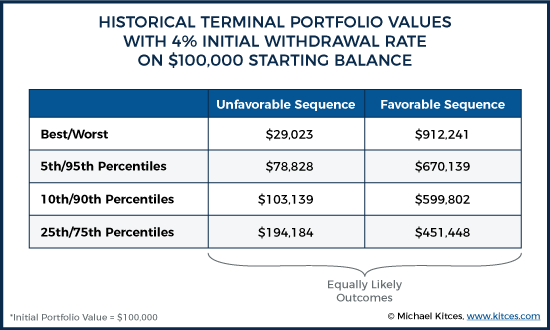

Interestingly, the potential impact is asymmetrical and favors the upside. That is, due to the power of compounding during bull markets, the magnitude of potential benefit from starting with a “good sequence” outweighs the magnitude of the potential detriment of starting with a “bad sequence.” In short, a good sequence provides more “good” than a bad sequence provides “bad.”

Michael Kitces, famous financial advisor and retirement researcher, notes how the extremely wide possibility of outcomes from different sequences dictates that investors still withdraw conservatively and smartly “just in case,” even though there exists the potential for massive upside. He explains:

…on average a 4% initial withdrawal rate results in the retiree finishing with nearly triple the original principal, on top of sustaining an initial withdrawal rate of 4% adjusted annually for inflation! In fact, in only 10% of the scenarios does the retiree even finish with less than 100% of their starting principal (and in only one of those scenarios does the final value run all the way down to having nothing at the end, which of course is what defines the 4% initial withdrawal as “safe” in the first place).

As usual, hope for the best but plan for the worst.

Sequence of Return Risk Charts

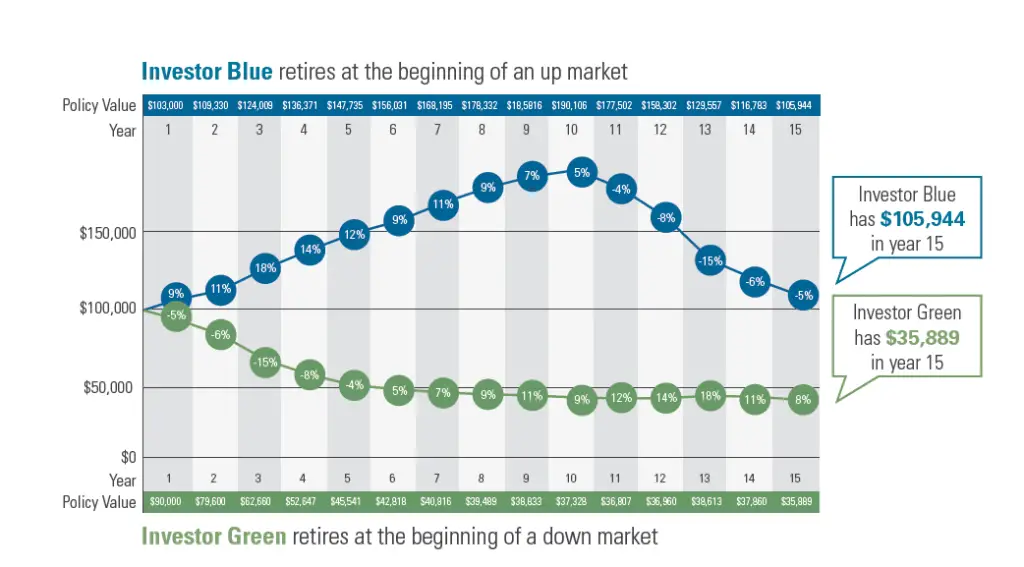

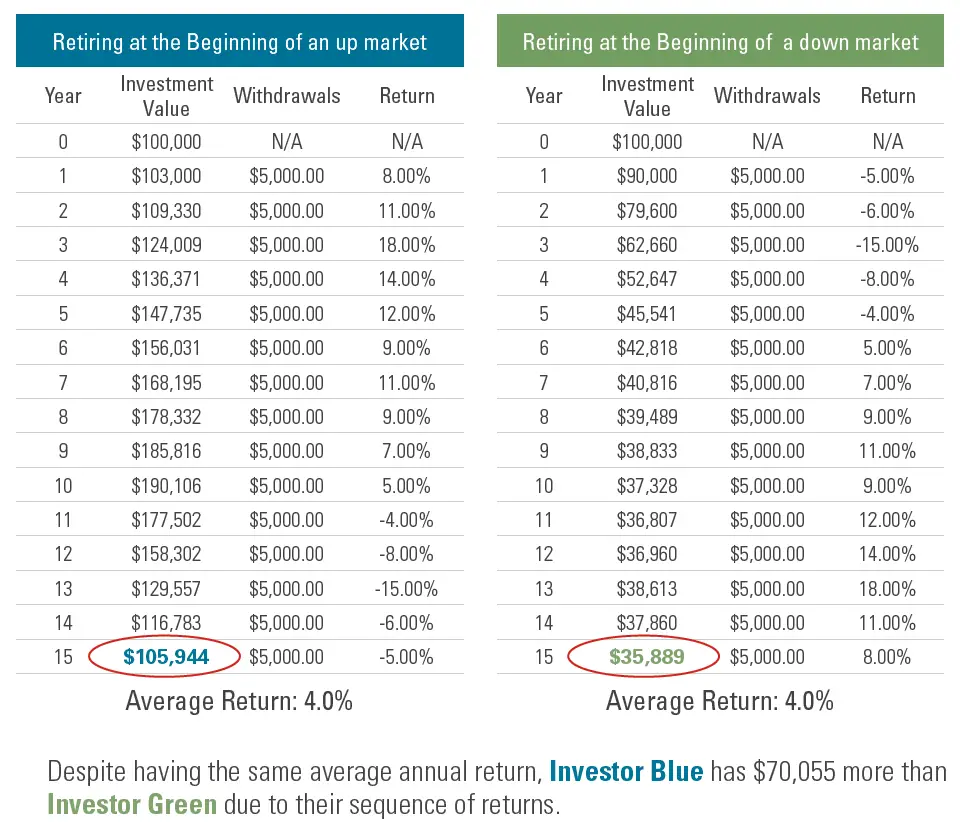

The graph below illustrates the above points – that even with the same average annual return, the investor entering retirement in a bull market is far better off later than the investor who enters retirement during a bear market – for a hypothetical scenario:

Here's a chart for the same data:

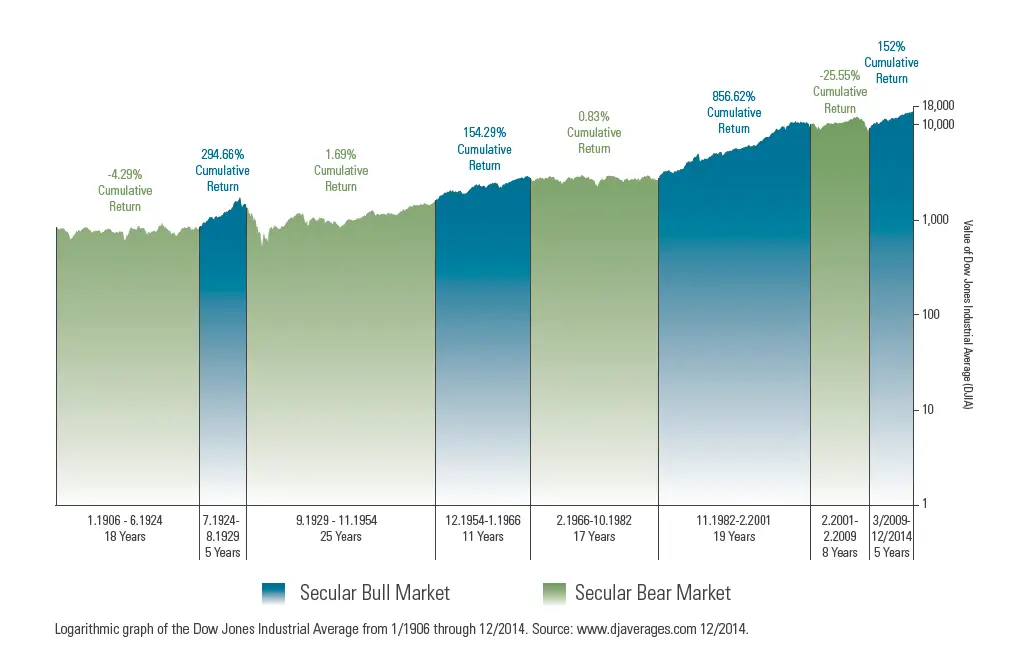

The graph below illustrates how the two sides of the luck coin have played out historically using the empirical data:

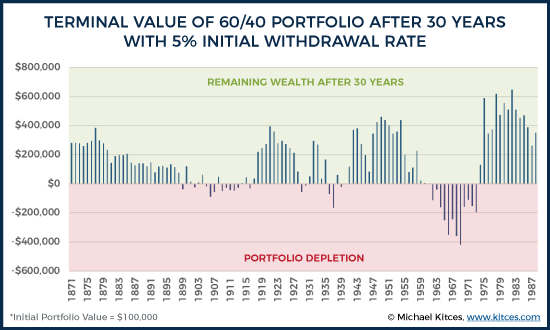

Kitces illustrates the dangerous implications of what's shown above – that even bumping up to just a 5% withdrawal rate (from 4%) fails 25% of the time in historical scenarios with a 60/40 portfolio:

Kitces also illustrates the wide variability of possible outcomes and potential upside of sequence risk:

Sequence of Return Risk and Asset Types

Naturally, assets like treasury bonds – especially those of shorter durations – have comparatively less sequence of return risk than things like stocks, gold, and real estate. That is, the year-to-year returns of bonds are more predictable and less volatile than the latter assets. On the extremes, the risk-free asset (1-month T Bills) has zero sequence risk and leveraged equities have the most sequence risk.

Bonds are typically increasingly added as time passes for precisely that reason, to decrease the portfolio’s overall volatility and risk. This is why diversification becomes even more important near retirement in favor of capital preservation over massive gains. A young investor with a 30-year time horizon can afford to be – and arguably should be – invested in 100% stocks precisely because they don’t need to worry about sequence risk early in the accumulation phase, during which they’re also likely not making any withdrawals.

That is, young investors can afford to have bad years – and even strings of consecutively bad years – from which their portfolio can later recover. A retiree doesn’t have that luxury; for them, consistency of returns is as important as – and arguably more important than – the size of those returns.

Mitigating Sequence of Return Risk – Possible Solutions

A seemingly obvious answer to reduce sequence risk is to try to change the portfolio in anticipation of market behavior, known colloquially as market timing. Unfortunately, the evidence tells us this doesn’t really work, and market timing is actually usually more harmful than helpful.

Another obvious solution is to simply work a few more a years to increase the starting value of the portfolio entering retirement, but that doesn’t sound fun.

So what about tackling spending and how that affects withdrawals?

The first idea is to simply cut expenses during bad market years to save money so that you can live normally when the market recovers.

A more involved, likely more optimal approach is to use specific decision criteria like Jonathan Guyton's “guardrails” to indicate when to pull back on withdrawals and spending. If your withdrawal percentage is creeping up naturally, i.e. your portfolio’s value is decreasing to where your necessary withdrawal amount to cover expenses is increasing as a percentage of portfolio value, then cut expenses.

For example, with a portfolio value of $1,000,000 and annual living expenses of $40,000, you have a 4% withdrawal rate, said to be a pretty safe estimator for retirement planning. If your portfolio value dips to $900,000, your $40,000 in expenses now comprise 4.4% of the portfolio’s value. The retiree may decide to cut expenses if their withdrawal rate reaches 5%, for example, and give themselves a raise if their withdrawal rate reaches 3%. This is likely a more sensible approach than simply letting market performance per se dictate spending.

Kitces maintains that what’s objectively even better than that is to make small, permanent cuts to expenses where you can. This invariably decreases the withdrawal percentage and permanently improves the portfolio value through compounding in future years when you still don’t have that particular expense. Due to the power of compounding, he suggests that these small cuts in expenses are ironically more impactful over the rest of the retirement horizon than the aforementioned larger but temporary cuts.

Recent research from Michael Kitces and Wade Pfau suggests that a tactical asset allocation strategy layered on top of this variable spending criteria idea can further mitigate sequence risk by doing the precise opposite of the traditional wisdom – getting more aggressive by allocating more to stocks as your retirement progresses.

Sounds crazy, right? The traditional wisdom that seems perfectly intuitive is a declining equity glidepath, which says to decrease risk by allocating more to bonds as time goes on. The idea to do the opposite is not as farfetched as it may seem at first glance. Given the “bad” scenario of a market downturn at the beginning of one’s retirement that recovers later, the research from Kitces suggests that on average, it is better to be more in stocks later to ride that recovery back up, rather than crashing with mostly stocks (which will hurt worse) and recovering with mostly bonds (which will recover less of the portfolio’s value).

This is perhaps a difficult concept to accept and put into practice, but Kitces suggests you can easily do this by simply being more conservative than you already would be when going into retirement, and then titrate up in equities to be slightly less conservative as time goes on. He’s not at all advocating that retirees should be shifting to 100% equities.

A realistic example would be going into retirement with something ultra-conservative like 30/70 stocks/bonds and then gradually moving to 50/50 or whatever your “normal” risk tolerance would allow. As he puts it, “shelter in the bond tent” for the first 10 years, spend it down, and then “get back to normal” with the portfolio you would have had in the first place as you emerge.

Using a Withdrawal Policy Statement

The aforementioned criteria and tactics could be put into a Withdrawal Policy Statement (WPS) that establishes strict parameters for how portfolio withdrawals will be handled, similar to how an Investment Policy Statement (IPS) establishes guidelines for how the portfolio’s investments will be handled on an ongoing basis.

These Statements help eliminate any emotional, knee-jerk reactions to market fluctuations that will likely be more harmful than helpful. They also eliminate needless stress over uncontrollable, unpredictable market volatility, as well as the subsequent worry about whether or not you’re doing the right thing with the portfolio based on that volatility. Without adherence to these parameters and clear thresholds, you are likely to make more short-term adjustments to the portfolio and may miss the forest for the trees. Setting parameters means market fluctuations are only actionable if they exceed the bounds you’ve set for the portfolio’s value, withdrawal percentage, etc. Simply having the plan makes it easier to follow the plan.

Conclusion

Sequence of return risk is often overlooked and can potentially be massively detrimental to your financial retirement plans. Understand the risks of a “bad sequence” when entering retirement and establish a strategy to mitigate it, all while hoping for some good luck and a “good” sequence.

Do you employ tactics to reduce sequence risk? Let me know in the comments.

Are you nearing or in retirement? Use my link here to get a free holistic financial plan and to take advantage of 25% exclusive savings on financial planning and wealth management services from fiduciary advisors at Retirable to manage your savings, spend smarter, and navigate key decisions.

Disclaimer: While I love diving into investing-related data and playing around with backtests, this is not financial advice, investing advice, or tax advice. The information on this website is for informational, educational, and entertainment purposes only. Investment products discussed (ETFs, mutual funds, etc.) are for illustrative purposes only. It is not a research report. It is not a recommendation to buy, sell, or otherwise transact in any of the products mentioned. I always attempt to ensure the accuracy of information presented but that accuracy cannot be guaranteed. Do your own due diligence. I mention M1 Finance a lot around here. M1 does not provide investment advice, and this is not an offer or solicitation of an offer, or advice to buy or sell any security, and you are encouraged to consult your personal investment, legal, and tax advisors. Hypothetical examples used, such as historical backtests, do not reflect any specific investments, are for illustrative purposes only, and should not be considered an offer to buy or sell any products. All investing involves risk, including the risk of losing the money you invest. Past performance does not guarantee future results. Opinions are my own and do not represent those of other parties mentioned. Read my lengthier disclaimer here.

Are you nearing or in retirement? Use my link here to get a free holistic financial plan and to take advantage of 25% exclusive savings on financial planning and wealth management services from fiduciary advisors at Retirable to manage your savings, spend smarter, and navigate key decisions.

Hi John, thanks again for another insightful article. This one combined with the 4% rule article has me thinking about the best way to withdraw in retirement. Let’s take a simple portfolio like 40% US stocks, 20% international stocks and 40% US bonds in a tax deferred account. Historically is it best to make the withdrawal and rebalance quarterly (or annually if you have limitations on the number of withdrawals such as the rule of 55)? Are there better strategies? Note I’m not referring to how much to withdraw but rather what assets to sell when withdrawing. I read in this article on the Buffett 90/10 portfolio that Tweak 1 performs better. Tweak 1 says that when stocks are up over the past year sell stocks and rebalance but if stocks are down sell bonds and don’t rebalance. I wonder if this only works for the 90/10 portfolio and annual rebalancing. This might be an interesting article for you to write.

Thanks, Simon. I do plan to do a piece on withdrawal strategy at some point. Can’t know what’s optimal ahead of time but yes I’d likely sell more of the asset that is “up.”

Thanks – I look forward to the article.

As an FYI I’ve ticked the option to subscribe when posting and I’ve subscribed on the main page for new articles but I’ve never received an email notification from the website. I did check my spam box as well just in case.

Hi John, thanks again for the blog and associated information. Very helpful.

Question: What do you think of the “bucket” strategy as a way to mitigate sequence of return risk? Ever think of writing a post about it? I’m nearing retirement. I plan to draw on my portfolio in about 10 years and looking for the best way to get it into a lower volatility allocation and from there a strategy to mitigate sequence of return risk.

thanks! Danny

Hey Danny. I actually just replied to someone on Reddit about this the other day. Like dividends, “bucket” and “bond tent” and the like are just mental accounting, and typically are a friendlier description of what is effectively a rising equities glidepath, which doesn’t have quite the same ring to it. Sounds nice intuitively and arguably has psychological benefits, but it improves neither portfolio efficiency nor the probability of a successful retirement withdrawal outcome (SWR). Of course, under any dedicated scrutiny, this should be obvious, as target date funds do the precise opposite of a “bond tent.”

Moreover, a rising equities glidepath exposes the investor to no less sequence risk than a constant asset allocation of the same average equities exposure over the period, with the latter also being simpler to implement.

I am indeed planning to do a blog post on this mental accounting device at some point.

As I prepare for an early FatFIRE retirement, I’m worried about sequence of return risk. But, since I could go back to work anytime and have an overall high risk tolerance as a former entrepreneur, I’d love an article exploring a conservative level of margin debt used strategically in a rules-based way, as a potential solution to the Sequence of Return Risk problem.

I.e. if the market drops and this year’s “safe withdrawal” would be more than 4% of current portfolio value, instead of selling securities use a margin loan for anything over the 4% of current portfolio value. Then, when the portfolio recovers X years later, implement a rules-based approach to paying down the margin debt by selling securities only once the market has recovered.

I bet you could implement a rule where the leverage stays pretty low but helps meaningfully with Sequence of Return risk. Plus, when the markets are down short-term interest rates are usually lower as well (the fed put). Furthermore, using a brokerage with low margin rates and high allowed leverage ratios (i.e. Interactive Brokers with a Portfolio Margin setting) should provide a lot more headroom and lower risk vs a typical brokerage setup.

Let me know if you know of any research or articles on this topic, I’m super curious.

Thank you for bringing this sequencing info to light!

I am 61 and about to retire and am trying to put together the best portfolio to begin my retirement.

I utilized the Monte Carlo Simulations in Portfolio Visualizer with a setting of the first 10 years of 30 years being the worst…and WOW…does that make a difference!

After many different runs and portfolios I found the following mix to be successful in what I am looking for. I’d be interested in your thoughts.

10% SSO

10% TBT

30% TLT

40% QQQ

10% VTI

Thanks again for this info on sequencing and for all of your other blog posts.

Thanks, Ron. I can’t provide personalized advice, but I wouldn’t be using leverage at all in retirement. Sounds like you might be data mining relying too much on backtests. The portfolio you listed is heavily concentrated in tech and has no international exposure. And note TBT is shorting bonds. Wouldn’t make sense to hold that alongside TLT; they’re basically cancelling each other out.

Thank you for producing such a valuable site. I have just about read all of your posts and related comments and have really learned quite a bit.

I am 61 and about to retire and I happen to just read this Sequence post and it is giving me some pause. I thought the old 4% Withdrawal Rate was outdated, but given that I might be starting my retirement at the beginning of down market I might need to seriously revisit that topic.

Thanks again.