Financially reviewed by Patrick Flood, CFA.

Asset allocation refers to the ratio among different asset types in one's investment portfolio. Here we'll look at how to set one's portfolio asset allocation by age and risk tolerance, from young beginners to retirees, including calculations and examples.

Disclosure: Some of the links on this page are referral links. At no additional cost to you, if you choose to make a purchase or sign up for a service after clicking through those links, I may receive a small commission. This allows me to continue producing high-quality content on this site and pays for the occasional cup of coffee. I have first-hand experience with every product or service I recommend, and I recommend them because I genuinely believe they are useful, not because of the commission I may get. Read more here.

In a hurry? Here are the highlights:

- Asset allocation refers to the ratio of different asset classes in an investment portfolio, and is determined by one's investing objectives, time horizon, and risk tolerance.

- Asset allocation is extremely important, more so than security selection, and explains most of a portfolio's returns and volatility.

- Stocks tend to be riskier than bonds. Holding two uncorrelated assets like stocks and bonds together reduces overall portfolio volatility and risk compared to holding either asset in isolation.

- There are a few simple formulas to calculate asset allocation by age, suitable for young beginners all the way to retirees, and appropriate for multiple risk tolerance levels.

- There is no “best” asset allocation. What is appropriate for you may not be appropriate for someone else. The optimal portfolio can only be known in hindsight.

- M1 Finance makes it extremely easy to set, maintain, and rebalance a target asset allocation.

Contents

Asset Allocation Video

Prefer video? Watch it here:

What Is Asset Allocation?

Asset allocation simply refers to the specific mix or distribution of different asset types in one's investment portfolio based on personal goals, risk tolerance, and time horizon. Goals refer to things you want to do or buy, such as a downpayment on a house and/or retiring at age 55. Risk tolerance refers to how much risk you can handle without deviating from your strategy; we'll talk about this more in a second. Time horizon just means the time period for which you will hold the investment to meet your goal. For example, this could be 10 years for that house downpayment and 30 years for retirement.

Most people I've talked to don't know the term “asset allocation” until after learning it. Words used by the uninitiated to refer to this same idea include mix, distribution, and split. In this context, these all refer to the same thing. We're simply talking about a ratio of different asset classes, e.g. 60/40 stocks/bonds:

The three main asset classes are stocks/equities, fixed income, and cash or cash equivalents. Outside of those, in the context of portfolio diversification, people usually consider gold/metals and REITs to be their own classes too. Don't worry if all this sounds confusing right now.

Let's look at why asset allocation is important.

Why Is Asset Allocation Important?

These different asset classes behave differently during different market environments. The relationship between two asset classes is called asset correlation. For example, stocks and bonds are held alongside one another because they are usually negatively correlated, meaning when stocks go down, bonds tend to go up, and vice versa. That uncorrelation between assets offers a diversification benefit that helps lower overall portfolio volatility and risk. This concept becomes increasingly important for those with a low tolerance for risk and/or for those nearing, at, or in retirement, and equity risk factor diversification may be just as important as asset class diversification.

It's widely accepted that choosing an asset allocation is more important over the long term than the specific selection of assets. That is, choosing what percentage of your portfolio should be in stocks and what percentage should be in bonds is more important – and more impactful – than choosing, for example, between an S&P 500 index fund and a total market index fund. Vanguard actually determined that roughly 88% of a portfolio's volatility and returns are explained by asset allocation.*

Think of asset allocation as the big-picture framework or foundation upon which your portfolio rests, before moving on to the minutiae of selecting specific securities to invest in. We know that we can't consistently time the market or pick individual stocks with success. Asset allocation is one thing you can control that has a significant impact on your portfolio's behavior, and should thus be your primary focus.

Moreover, trust that staying disciplined with this framework on your investing journey will allow you to more easily reach your financial objectives and will improve the reliability of the expected outcome (i.e. a decrease in the dispersion of possible outcomes at retirement). You will come out far ahead compared to those who constantly tinker and change their strategy, spinning their wheels jumping to new shiny objects based on whatever the talking heads on TV are saying that week.

It's hard to sell someone a newsletter subscription around the relatively simple, unsexy idea of figuring out a personalized asset allocation, buying index funds, rebalancing annually, and staying the course. The temptation to stray from your asset allocation will be great when you see headlines about market crashes and the past performance of stock picks and sectors, but recognize that this is just survivorship bias and recency bias rearing their ugly heads.

Different investing goals obviously necessitate different asset allocations. Given a particular level of risk, asset allocation is the most important factor in achieving an investing objective. An investor who wants to save for a down-payment on a house in 10 years will obviously have a far more conservative asset allocation than an investor who is saving for retirement 40 years into the future.

Asset allocation is usually colloquially written and stated as a ratio of stocks to fixed income, e.g. 60/40, meaning 60% stocks and 40% bonds. Continuing the example, since bonds tend to be less risky than stocks, the first investor with a short time horizon may have an asset allocation of 10/90 stocks/bonds while the second investor may have a much more aggressive allocation of 90/10. We can extend that description to other assets like gold, for example, written as 70/20/10 stocks/bonds/gold, meaning 70% stocks, 20% bonds, and 10% gold.

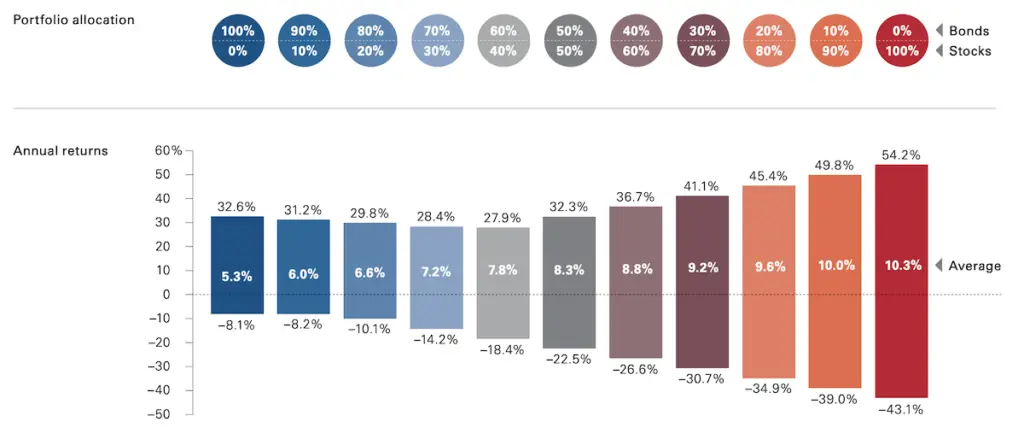

So what does all this look like in practice? The chart below shows the practical application, importance, and variability of returns of specific asset allocations comprised of two assets – stocks and bonds – from 1926 through 2019. Bars represent the best and worst 1-year returns.

As you can see, asset allocation affects not only risk and expected return, but also reliability of outcome. The chart also illustrates the expected performance of stocks and bonds. Stocks tend to exhibit higher returns, at the cost of greater volatility (variability of return) and risk. Bonds tend to exhibit the opposite – comparatively lower returns but with less risk. Once again, combining uncorrelated assets like these helps preserve returns while reducing overall portfolio volatility and risk. The subsequent percentage of each asset significantly influences the behavior and performance of the portfolio as a whole.

It's important to keep in mind in all this that past performance does not necessarily indicate future results. That is, there is no way for us to know the ideal asset allocation ahead of time. The optimal portfolio can only be known in hindsight. However, we can say with reasonable certainty that over the long term, investors are usually compensated more for taking on more systematic risk.

Does this mean you should take on the most risk possible for the greatest expected return? Probably not. Now that you see why asset allocation is important, let's look at how one's risk tolerance affects asset allocation.

Asset Allocation and Risk Tolerance

Investor behavior plays a big part in asset allocation in the form of risk tolerance. A successful asset allocation strategy requires that the investor is able to stick to it. Modern Portfolio Theory assumes all investors behave rationally and unemotionally. We know this isn't the case.

The investor is usually the cause of the failure of their investment plan, not the financial markets. As you might imagine, plans are typically abandoned during crashes or extreme bull markets. One of the mistakes most often made is the overestimation of one's tolerance for risk. Risk tolerance can be defined as the point at which price volatility (swinging movement) or drawdown (drops in value; loss of capital) causes you to change your behavior. Obviously, for a young investor with no experience, this point can be hard to assess.

For a hypothetical, simplistic, reductive example, suppose an investor determines that they cannot emotionally withstand seeing a loss greater than 20% or volatility, measured by standard deviation, greater than 10%. The chart above is using worst 1-year returns and not drawdowns specifically, but we might say this investor has a low tolerance for risk and estimate that this means they should be in nothing more aggressive than a 40/60 stocks/bonds portfolio, otherwise they may abandon their strategy at the worst possible time. This of course also assumes that the expected return of such an asset allocation would still allow them to meet their financial liability and achieve their goals. Note that the numbers I used here are made up, and the future may not look the same as the past.

Stocks are more risky than bonds. Buying stocks is a bet on the future earnings of companies. Bonds are a contractual obligation for a set payment to the bond holder. Because future corporate earnings – and what the company does with those earnings – are outside the control of the investor, stocks inherently possess greater risk – and thus greater potential reward – than bonds.

So why not just invest in bonds? Again, stocks tend to exhibit higher returns than bonds. Investing solely in bonds may not allow the investor to reach their financial goals based on their specific objective, and bonds have their own unique risks. Remember, risk and return are usually positively linked. Most investors have a need for risk simply because they require a rate of return greater than what 1-month Treasury Bills (the risk-free asset) alone can deliver. In most cases, by reducing the portfolio's risk, we must by definition also accept lower expected returns. In the interest of full disclosure, I say “most cases” because, as with everything, there are exceptions, such as the case with equity risk factors, especially when looking at short time periods,

Moreover, unexpected inflation, for example, can potentially be damaging to a bond-heavy portfolio. On the flip side, investing solely in stocks maximizes volatility and risk, creating the very real possibility of losing money over the short term. Holding bonds reduces the impact of the risks of holding stocks. Holding stocks reduces the impact of the risks of holding bonds. Such is the beauty of diversification: Depending on time horizon and market behavior, holding two (or more) uncorrelated assets can result in higher returns and lower risk than either asset held in isolation, with a smoother ride.

An entire post could be dedicated to behavioral finance and risk tolerance alone. It is highly personal and involves complex psychology from usually-irrational human behavior that we can't reliably predict ourselves. In investing, unfortunately, the stomach is usually more powerful than the mind. I've got a separate post on biases that investors often succumb to, usually unknowingly.

William Bernstein suggested that an investor can evaluate their risk tolerance based on how they reacted to the Global Financial Crisis of 2008:

- Sold: low risk tolerance

- Held steady: moderate risk tolerance

- Bought more: high risk tolerance

- Bought more and hoped for further declines: very high risk tolerance

Pick a risk level that lets you sleep at night. Again, most investors severely overestimate their tolerance for risk, only realizing their true risk tolerance during a market crash when their portfolio value tanks. It's also been theorized that investors may be embarrassed to admit to their advisor – or to themselves – that they have a low tolerance for risk. Don't be.

It is imperative to have realistic expectations of both the markets and of one's own behaviors. The behavioral aspect of investing is unfortunately very real and can have significant consequences. Emotional responses to one's environment – in this case a financial environment – are hardwired in the human brain. Are you going to panic sell if your portfolio value drops by 57% like it did for an S&P 500 index investor in 2008?

Also keep in mind that stocks tend to do worse when you are doing worse. That is, your human capital tends to suffer at the same times that your investment capital suffers, so be sure to have an emergency fund established to avoid being forced to sell low and lock in losses just because you need the income during an economic downturn. Lastly, acknowledge and account for cognitive biases such as loss aversion, the principle that humans are generally more sensitive to losses than to gains, suggesting we tend to do more to avoid losses than to acquire gains.

Vanguard has a useful page showing historical returns and risk metrics for different asset allocation models that may help your decision process. Once again, remember that same performance seen on that page may not occur in the future.

The best asset allocation is the one that allows you to stay invested through good times and bad. It's easy to say you'll stay invested through a major crash, but this is much easier said than done, and is something that must be experienced to be fully understood. It's also easy to show that a portfolio of 100% stocks has higher expected returns, but if you sell during a market crash due to the extreme volatility and seeing your portfolio plummet, you probably would have been better off with a more conservative 60/40 the entire time.

Note too that deviating from one's strategy does not have to come in the form of selling during a crash. This can also mean not investing new money due to being scared of the markets after a crash, or delaying investments because you think the market looks expensive. Over the long term, all these behaviors increase risk by decreasing total return and reliability of outcome.

Larry Swedroe notes: “The discipline to stay the course with an asset allocation is in all likelihood the greatest determinant of returns in the long run, more so than asset allocation itself.”

Trust that you will go through a period of market turmoil where your risk tolerance and subsequent adherence to your investment plan and asset allocation will be tested.

Asset Allocation Questionnaire

Vanguard has a neat asset allocation questionnaire tool that can be used as a starting point. The questionnaire incorporates time horizon and risk tolerance. You can check it out here. While it may be a useful exercise, it’s still only one piece of the puzzle and doesn’t factor in things like current mood, current market sentiment, external influence etc. Be mindful of these things and try to be as objective as possible. If you answer these questions during a prosperous bull market, for example, your attitude will almost certainly be overly optimistic and your answers will indicate a maximum risk tolerance higher than your true level. It doesn't make much sense to try to assess one's maximum risk tolerance during ideal market conditions. It is probably best to take these questionnaires after a market decline.

Asset Allocation by Age Calculation

There are several quick, oft-cited model calculations used for dynamic asset allocation of a portfolio of stocks and bonds by age, moving more into bonds as time passes because they're safer. For the sake of clarity and consistency of discussion, we're going to assume a retirement age of 60.

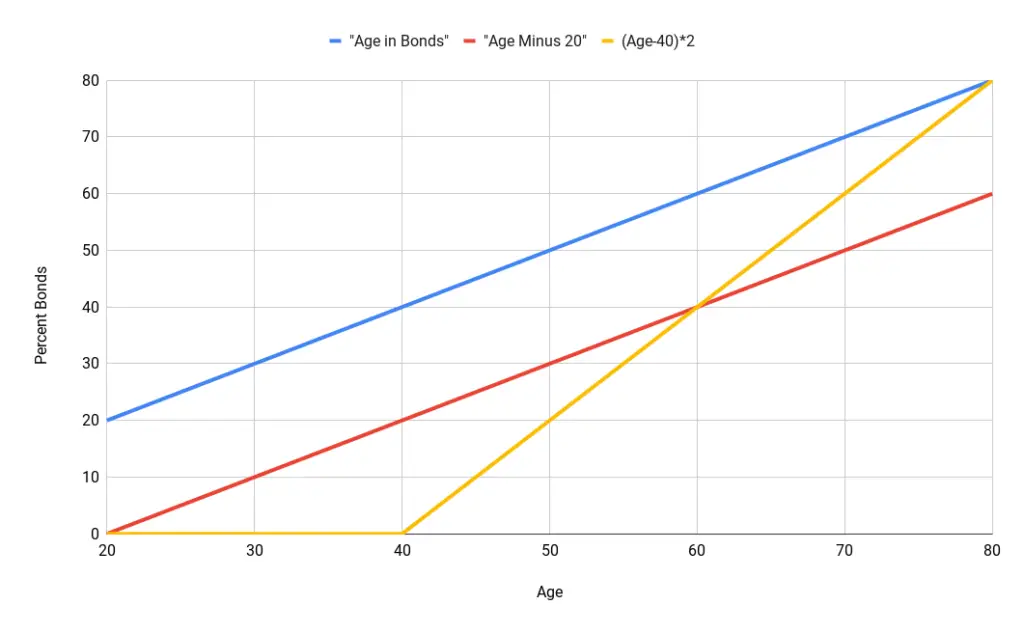

- The first and simplest adage is “age in bonds.” A 40-year-old would have 40% in bonds. This may indeed be fitting for an investor with a low tolerance for risk, but is too conservative in my opinion. In fact, this conventional wisdom that has been repeated ad nauseam goes against the recommended asset allocations of all the top target date fund managers. This calculation would mean a beginner investor at 20 years old would already have 20% bonds right out of the gate. This would very likely stifle early growth when accumulation is more important at the beginning of the investing horizon.

- Another general rule of thumb is a more aggressive [age minus 20] for bond allocation. This calculation is much more in line with expert recommendations. This means the 40-year-old has 20% in bonds and the young investor has a portfolio of 100% stocks and no bonds at age 20. This also yields the stalwart 60/40 portfolio for a retiree at age 60.

- A more optimal, albeit slightly more complex formula may be something like [(age-40)*2]. This means bonds don't show up in the portfolio until age 40, allowing for maximum growth while early accumulation is more important, then accelerating the shift to prioritizing capital preservation nearing retirement age. This calculation seems to most closely follow the glide paths of the top target date funds.

Generally speaking, it could be said that these 3 formulas coincide with low, moderate, and high risk tolerances, respectively.

I've illustrated these three calculations below in the next section.

Asset Allocation by Age Chart

I've illustrated the 3 formulas above in the chart below:

Asset Allocation Examples

Let's look at some examples of asset allocation models by age.

Using [age minus 20] for bond allocation, a starting age of 20, and a retirement age of 60, a one-size-fits-most allocation would be 80/20. This fits a young investor with a low risk tolerance and a middle-aged investor with a moderate risk tolerance.

Both the [age minus 20] formula and the [(age-40)*2] formula would result in a traditional 60/40 portfolio – considered a near-perfect balance of risk and expected return – for a retiree at age 60.

Several lazy portfolios exemplify notional asset allocation models:

- Warren Buffett Portfolio – 90/10

- No Brainer Portfolio – 75/25

- Larry Swedroe Portfolio – 30/70

Here are a couple fun facts. While two of the formulas above yield the famous 60/40 portfolio – considered a good balance of risk and expected return – at a retirement age of 60, Warren Buffett himself has instructed for his wife's inheritance to be invested in a 90/10 portfolio.

Historically, the highest risk-adjusted return (the greatest return per unit of risk) has been delivered by a 30/70 allocation of stocks to intermediate treasury bonds, which incidentally is the risk parity allocation for those two assets.

In any case, remember to rebalance regularly (annually or semi-annually is fine) so that your asset allocation stays on target. Rebalancing just means bringing the portfolio back to its target asset allocation, as it may shift over time. For example, if you have a portfolio of 50% stocks and 50% bonds and the stocks go up during the year by 10% and the bonds go down during the year by 10%, your asset allocation is now 55/45. Rebalancing sells stocks and buys bonds to bring it back to the intended 50/50.

You can rebalance anytime in a tax-advantaged account like an IRA or 401k without tax consequences, but if doing so in a taxable environment, you'd want to wait until after you've held the assets for 366 days to avoid short-term capital gains taxes, at least in the U.S.

Asset Allocation Mutual Funds and ETFs

In case you didn't know, a target date fund does all this asset allocation stuff for you behind the scenes. This is a type of mutual fund that you select based on your intended retirement year – the “target date” – and it shifts away from stocks into bonds as you age and near retirement, just like we've discussed.

You'll typically have a range of these to choose from in your 401k from your employer. Read the details on these mutual funds to make sure they match your risk tolerance. It may not immediately be clear when or how quickly the shift from stocks to bonds occurs.

In the interest of full disclosure, I usually find target date funds to be too conservative and suboptimal in their attempted one-size-fits-most approach. You also typically pay a bit extra in fees for their convenience. That said, target date funds are great for someone wanting to be completely hands-off; they're as simple as it gets.

Blackrock/iShares have also offered “asset allocation ETFs” for over a decade now as part of their “Core” series. But first, note these are not target date funds like I just described. These invest in a single asset allocation based on a particular risk tolerance, e.g. 40/60 stocks/bonds for their “Moderate Allocation ETF” for which the ticker is AOM, and that allocation does not change. Secondly, these are “fund-of-funds” products, meaning it's just a single fund that holds a small handful of plain vanilla index funds that you could buy yourself at lower fees. They also seem to favor corporate bonds, which is not ideal in my opinion. Other ETFs in their lineup include AOA (Aggressive; 80/20), AOR (Growth; 60/40), and AOK (Conservative; 30/70).

Then there are some slightly more advanced, exotic products that use leverage to provide enhanced exposure to a diversified mix of assets. Their details are beyond the scope of this article, but I'll mention them briefly. NTSX is 90/60 (1.5x leverage on traditional 60/40) and SWAN is 70/90.

Asset Allocation in Retirement

Growth becomes less important near, at, and in retirement in favor of capital preservation. This means minimizing portfolio volatility and risk, such as with the All Weather Portfolio. This is why diversifiers like bonds become more necessary at the end of one's investing horizon, providing stability and downside protection. Retirees also shouldn't shy away from risk factor diversification. Creating a balanced mix of different assets is the best method of de-risking the portfolio.

The shorter one's time horizon is, the more important diversification becomes. This has just as much to do with preserving your wealth as it does with a type of risk called sequence risk. Sequence risk refers to the risk of the timing of withdrawals hurting a portfolio's returns, which is why decreasing the portfolio's potential variability of annual returns is important in retirement. The greater the volatility of the investment, the greater the sequence risk for the portfolio.

The expected average annualized return of your investment portfolio is not going to happen every single year. The order of annualized returns doesn’t matter during the accumulation phase, so sequence risk isn't really an issue for young investors, as they have decades to accumulate wealth and they're typically not making any withdrawals during that phase. That is, young investors can afford to have bad years – and even strings of consecutively bad years – from which their portfolio can later recover.

Retirees don't have this luxury of waiting, as expenses are constantly happening every month of every year in retirement. During retirement, you can’t recover money you have spent, so a bear market for a retiree in 100% stocks, for example, could be disastrous for the rest of their retirement, as they'll still need to make those withdrawals to cover expenses during the market downturn that won't be replenished by any new deposits.

Sequence risk is why many people initially planning to retire during the Global Financial Crisis of 2008 had to continue working for a few more years. This sort of timing is out of the control of the investor, but a good retirement plan and subsequent asset allocation will reduce the potential negative impact of this sequence risk. Investors can also mitigate the effects of sequence risk by saving more than they think they need for retirement, and then trying to withdraw comparatively less money during poor performance years.

I delved into the details of sequence risk more here.

Similarly, risk tolerance also remains important for retirees. After you've reached your financial objective by meeting your liability-matching portfolio (LMP), you no longer need to be heavily invested in risky assets like stocks. This is called risk avoidance. Once you've won the game, stop playing.

Someone with a high net worth will likely have a pretty conservative asset allocation, or at least probably should. They have the capacity – and perhaps the tolerance – for risk, but they no longer have the need for risk. Remember loss aversion; you will regret much more losing, say, half of your portfolio value by staying mostly in stocks than theoretically missing out on the greater gains from having a riskier, more aggressive portfolio. Do the math on your burn rate of capital outflows for liabilities in retirement and make sure your asset allocation is dialed in to match.

Retirees may also desire to simply use stock dividends and/or bond interest as income, which will influence asset allocation.

Again, my preferred formula above (number 3) accelerates the shift to bonds after age 40. For a 70-year-old retiree, for example, it yields an asset allocation of 40/60 stocks/bonds.

Are you nearing or in retirement? Use my link here to get a free holistic financial plan and to take advantage of 25% exclusive savings on financial planning and wealth management services from fiduciary advisors at Retirable to manage your savings, spend smarter, and navigate key decisions.

Asset Allocation Models By Age – A Table

To illustrate this idea of asset allocation shifting as time passes, below is a table showing various hypothetical asset allocations models by age for three hypothetical risk tolerances. This will give you an idea of what yours might look like and how it will change as you get older. As a simplistic example, I'll use:

Low risk tolerance = “age in bonds”

Medium risk tolerance = “age minus 10”

High risk tolerance = “age minus 20”

Remember, asset allocation is written as a ratio of stocks to bonds, such as 80/20, which means 80% stocks and 20% bonds.

| Age | Low Risk Tolerance | Medium Risk Tolerance | High Risk Tolerance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 20 | 80/20 | 90/10 | 100/0 |

| 30 | 70/30 | 80/20 | 90/10 |

| 40 | 60/40 | 70/30 | 80/20 |

| 50 | 50/50 | 60/40 | 70/30 |

| 60 | 40/60 | 50/50 | 60/40 |

| 70 | 30/70 | 40/60 | 50/50 |

| 80 | 20/80 | 30/70 | 40/60 |

| 90 | 10/90 | 20/80 | 30/70 |

| 100 | 0/100 | 10/90 | 20/80 |

Vanguard has a useful page showing historical returns and risk metrics for different asset allocation models that may help your decision process. Once again, use this as an informational tool in your arsenal, but also remember that same performance seen on that page may not occur in the future.

When To Change Asset Allocation

Your asset allocation doesn't have to be set in stone forever. It can change based on life events or new information.

Life events could be things like having children or getting married or divorced. These things change your future needs, and your asset allocation should be updated to match those revised financial liabilities.

What I mean by new information is things like:

- Having more money than you need for retirement.

- Being close to the amount of money you need for retirement.

- Realizing you initially overestimated your risk tolerance. This one is very likely to happen.

If you end up with more money than you need to cover your expenses and lifestyle in retirement, that's a great problem to have. This might mean you choose to leave some portion to heirs. In this case, the asset allocation for that portion should likely be more aggressive than yours, as the younger heirs may have a longer time horizon. Suppose you realize you only need half of your retirement savings and you want to bequeath the other half. Also suppose your conservative asset allocation in retirement is 20/80 but you determine an appropriate allocation for the half to be left is 80/20. This results in an overall asset allocation of 50/50 for the total amount.

If the market has been kind and you're close to hitting your retirement savings number sooner than expected, there's no reason to continue taking on unnecessary risk, as you no longer require the rate of return that initially dictated your aggressive allocation. Now you can lower the risk of the portfolio by decreasing the equities position and still comfortably meet your financial goals.

The most likely scenario that happens for many people, as I stated earlier, is overestimating one's tolerance for risk. This is almost always realized during and directly following a major market crash. View this as a learning experience, allowing you to reassess your true risk tolerance that will prevent you from making emotion-based investment decisions in the future.

The Best Books on Asset Allocation

Interested in reading some books on asset allocation? Some of the best names in the business – Roger Gibson, William Bernstein, Meb Faber, and Rick Ferri – have written some:

- All About Asset Allocation by Rick Ferri

- The Intelligent Asset Allocator by William Bernstein

- Asset Allocation: Balancing Financial Risk by Roger Gibson

- Global Asset Allocation: A Survey of the World's Top Asset Allocation Strategies by Meb Faber

- Rational Expectations: Asset Allocation for Investing Adults by William Bernstein (probably only for advanced investors who want some dense math; beginners should probably skip this one)

Conclusion

Asset allocation is an extremely important foundation for one's investment portfolio. It is dependent on the investor's time horizon, goals, and risk tolerance. There are several simple formulas that can be used in helping determine asset allocation by age. Take the time to assess all these factors for yourself. For a hands-off approach, you may be interested in a lazy portfolio or a target date fund. The latter should be available in your 401k through your employer.

M1 Finance makes it easier than any other online broker to execute on your intended asset allocation, because your portfolio is visualized in a simple “pie” format, you're able to input and maintain a specific asset allocation without doing any calculations, and M1 automatically directs new deposits to maintain your target allocations. M1 is perfect for implementing a lazy portfolio, they offer free expert portfolios and target date funds, and they also have zero fees and commissions.

Asset Allocation FAQ's

Lastly, here are some frequently asked questions about asset allocation.

Why is asset allocation important?

Asset allocation is important because it determines the investor's portfolio's risk/return profile much more than the specific assets themselves, and should thus be adjusted based on the investor's goal(s), time horizon, and risk tolerance.

What is the purpose of asset allocation?

Asset allocation determines an investment portfolio's risk/return profile much more than the specific assets themselves, and should thus be adjusted based on the investor's goal(s), time horizon, and risk tolerance.

Does asset allocation matter?

Asset allocation matters more than you probably realize. It massively influences a portfolio's risk/return profile much more than the specific assets themselves, and thus must align with the investor's goal(s), time horizon, and risk tolerance.

What asset allocation should I have?

This question has no simple answer and obviously depends on your personal goal(s), time horizon, and risk tolerance. That's sort of the point of this entire blog post.

How does asset allocation work?

Since asset allocation significantly affects a portfolio's risk and return characteristics, it should obviously align with the investor's personal goal(s), time horizon, and risk tolerance, and thus shifts over time and as major life events happen.

What is an example of asset allocation?

An example of asset allocation is 60% stocks and 40% bonds, written as 60/40.

What is a good asset allocation?

A “good” asset allocation is highly personal and is going to depend on the investor's goal(s), time horizon, and risk tolerance. 60% stocks and 40% bonds – written as 60/40 – is considered a good balance of risk and expected return.

What is a 70/30 asset allocation?

A 70/30 asset allocation means 70% stocks and 30% bonds. The first number refers to the stocks allocation and the second number refers to the fixed income allocation.

What is the best asset allocation?

There is no single “best” asset allocation, as this is going to depend on the investor's personal goal(s), time horizon, and risk tolerance. 60% stocks and 40% bonds – written as 60/40 – is considered a good balance of risk and expected return.

References

* Vanguard, The Global Case for Strategic Asset Allocation (Wallick et al., 2012).

Disclaimer: While I love diving into investing-related data and playing around with backtests, this is not financial advice, investing advice, or tax advice. The information on this website is for informational, educational, and entertainment purposes only. Investment products discussed (ETFs, mutual funds, etc.) are for illustrative purposes only. It is not a research report. It is not a recommendation to buy, sell, or otherwise transact in any of the products mentioned. I always attempt to ensure the accuracy of information presented but that accuracy cannot be guaranteed. Do your own due diligence. I mention M1 Finance a lot around here. M1 does not provide investment advice, and this is not an offer or solicitation of an offer, or advice to buy or sell any security, and you are encouraged to consult your personal investment, legal, and tax advisors. Hypothetical examples used, such as historical backtests, do not reflect any specific investments, are for illustrative purposes only, and should not be considered an offer to buy or sell any products. All investing involves risk, including the risk of losing the money you invest. Past performance does not guarantee future results. Opinions are my own and do not represent those of other parties mentioned. Read my lengthier disclaimer here.

Are you nearing or in retirement? Use my link here to get a free holistic financial plan and to take advantage of 25% exclusive savings on financial planning and wealth management services from fiduciary advisors at Retirable to manage your savings, spend smarter, and navigate key decisions.

To implement bond percentage, how should we overlay bond duration within our retirement assets? For example, in Vanguard target date funds, people seeking to retire in 2050 are given the mutual fund equivalent of BND for their domestic bonds, but the weighted average duration on BND is only about 7 years, and although Fidelity describes the composition as 40/20/40 short-term, intermediate, and long-term respectively. Finally, we know you’ve said treasuries are superior to corporate bonds, which is another problem with BND.

In summary, as we look at glide paths, can you advise not only on what the weighted average duration in years we should seek along the way, but also if we need a ST/IT/LT distribution? What percentage should be TIPS vs standard? Thanks John! Amazing content on this site.

Thanks, Jordan! All else equal, I’m a fan of simply aiming to match bond duration to the investing horizon, which can be done by rebalancing between 2 bond funds once a year or so.

You keep saying this. Could you clarify or make a post about this concept of matching duration? For example, your Ginger Ale Portfolio starts as 10% EDV, but as you age the Portfolio becomes a mix of 2 other bond funds. Where does EDV go? How did you arrive at those other two funds? I would be interested in a hypothetical glide path for bonds. Thanks

Thanks for the suggestion, Jon. I should do a post on it. Basic idea is for the portfolio’s bond duration to equal the investing horizon, particularly for a bond-heavy portfolio, as a bond’s duration is the point at which price risk and reinvestment risk “cancel,” so that investor can be indifferent to interest rate changes. That can be done by rebalancing between a long term and short term bond fund as the years pass. And of course this works best for a known liability with a set due date, and retirement date is a little more murky. The concept is called immunization if you want to Google and read more in the meantime.

Hi John,

Thanks so much for putting together, analyzing and sharing all this information. Its well written, well organized and easy to understand. I sent it to my son (who is involved somehow in Robinhood stuff) to try to balance his perspective. We’ll see. I’m afraid that generation is in for some rude awakenings.

So I am 69 and convinced from all my analysis that I have more than enough money for me to live comfortably. And as you recommend, I should probably reduce risk and leave the gaming table. Some part of me doesnt want to leave money on the table if there is a long time horizon that effectively reduces risk. In some way, it becomes my heirs money so my performance dictates how much I leave to them. So I like your idea of maybe creating two pots of money, one for my retirement and a second separate account of money that I do not touch and invest it aggressively for my childrens future use. There must be people doing this kind of thing, correct? Is there some formal way? Or is it better just to have a single asset allocation averaging both these things?

thanks so much – I will keep reading

Steve

Thanks for the kind words, Steve! Indeed, people are doing that kind of thing. The place to start would probably be deciding on a goal figure for that legacy money to leave and then backing into an asset allocation based on that goal, time horizon, and expected returns. A financial professional should be able to help you do that at an hourly rate. Of course this is largely just a mental bucketing and the total pot would still be the average of the two. But you can also put that separate bucket in something like a 529 account or a trust.

Would it be reasonable to just pick an allocation (say, 80/20) and stick with it for the rest of your life (with appropriate rebalancing). Or is an age-based formula almost certainly smarter, and it’s just a question of which one to adopt?

Great question, Josh. Age-based is probably best for most people due to sequence risk. But if you’ve already got millions and can survive drawdowns, keeping an aggressive allocation in retirement is probably fine.

Thanks Mr Williamson for this insightful article!

I’ve always been hearing about the importance of AA but never got to know more about it until after reading this article.

This article is comprehensive yet easy enough for the layman!

Just a side comment: You may want to relook into the link for Vanguard’s study on returns for the various AA. I kept encountering the “Page Not Found” error.

Thanks!

Thanks!

Hi John,

I just wanted to tell you how much I appreciate your articles. There is tons of information out there, but a lot of it is loaded with jargon and insider terms, or is otherwise pretty obtuse stuff. Your writing is really comprehensive and very informative and clear as it doesn’t succumb to those traps. A very sincere thanks.

Wow thanks so much for the kind words, Erica! Really means a lot. That’s definitely my goal.

I can’t thank you enough for putting this information together and for making it so easy to understand. It’s been so helpful! My mother is 85, suffers from dementia and other health problems and her care expenses are skyrocketing at a time when market risks are growing by the day. I reviewed her portfolio two weeks ago and discovered to my horror that it was set up with an 85/15 AA. After reading this article I repositioned her account with a 30/70 AA similar to Ray Dalio’s All Weather Portfolio. It provides the income Mom needs to help meet her care expenses and protects against big losses while still offering good growth potential. It’s nice getting a good night’s sleep again!

Thanks, Jeff! Glad to hear it was helpful!

This is an excellent source of info. Thank you so much. My question is what is the limit with bond% in your opinion, given our potential lengthier lives in the future? If we go by option 3, (age-40)2, does it just continue on forever? Or, is there a bond limit that we would hit and stay? 60/40 seems optimal in your opinion, so when we hit that at 60, do we just stay or continue to allocate towards bonds until we hit mostly all bonds years after retirement? I worry about very little gains if we’re nearly all bonds. Opinion?

Thank you!

Thanks, Rich! Excellent question. I’ve actually been thinking about how I want to add some verbiage to this post to cover this concept.

When you enter the decumulation phase at retirement, the horizon basically becomes life expectancy, which, as you noted, has been increasing. Asset allocation (and specifically, risk tolerance) is dynamic and becomes highly personal; it can shift based on life events (e.g. having children, incurring large medical bills, etc.) and should be reassessed as these things happen.

I’m of the mind that if you win the game, i.e. accumulating enough to comfortably cover expenses in retirement, stop playing. This could mean going 100% short term treasury bonds. For other people who need to try to keep generating returns in retirement, they’d likely want at least some allocation to stocks, which would be based on the expected return necessary to cover expenses for the horizon of life expectancy.

Inflation risk also enters the conversation, so the retiree would want a shorter bond duration and/or TIPS. Annuities can also be an attractive option for part of the portfolio.

So to answer your question, I don’t think there’s an upper limit, but if the investor wants/needs to do 100% bonds (based on them being risk-averse by necessity or by desire), it doesn’t make much sense for them to not be 100% short treasury bonds, which are considered “risk-free.” Otherwise, I think some small allocation to stocks still makes sense. For example, something like 10/90 stocks to short bonds would be less risky and less volatile than 100% intermediate bonds. Historically, the highest risk-adjusted return has come from an AA around 30/70, but volatility and risk should reliably decrease as the stocks allocation decreases. Looking at it from the other direction, volatility and risk don’t increase much as you slide from 0% stocks (100% short bonds) to 5% or 10% stocks, but expected returns do, as you noted. This idea is illustrated on the Vanguard page of historical performance of different portfolio allocations.

So as usual, it just comes down the investor’s specific needs. A good advisor will perform a comprehensive needs analysis and provide a plan for decumulation that is suitable for the investor based on financial liabilities, values, and risk tolerance. This will usually include simulations (via Monte Carlo) to statistically estimate a range of possible outcomes, from which the most sensible retirement portfolio would be constructed.

Hope that all makes sense and helps answer your question!

Hi John,

Thank you for taking the time to put all of these articles together. For an investing novice with children I find a ton of value in your articles.

A couple of questions for you. I have a 6 & 4 year old with one on the way. I have been putting a few hundred dollars a month in a certificate for the past 3 years but the returns are laughable. I would like to take that money out and start a custodial account with M1. What portfolio would you recommend? Have you built one for this situation? My second question is should I start a portfolio for each child or would I get a better return if I put it all the money into one account? I’m working to “back pay” my 6 year olds account since I started the certificate a few years ago. My goal is to put $100 for each child per month into a portfolio. If I put it all in one account I h e no idea how I would divide it up when they are older.

Thank you in advance for your input!

Ned, that’s awesome! Really glad you’re getting some value out of this stuff!

Depends entirely on time horizon, e.g. are these intended to be used for college at age 18 or for their retirement at age 60? If the latter, I’d do 100% VT and call it a day. If the former, maybe something that minimizes volatility and risk but still gets decent returns like the Golden Butterfly Portfolio.

Returns would be identical whether it’s one account or two, so that just comes down to the time/effort you want to put into setting the accounts up now and then transferring them later. You’re right, might be easier to just do two accounts so you don’t have to sell shares and split one later.

Hope this helps!

Hi John,

Thank you for your response. Yes, my intent is to fund retirement accounts for them. Please excuse my ignorance, but when you say VT are talking about the Vanguard Total World Stock Index Fund ETF? I just googled VT and that is what came up.

Thank you for your recommendation on either doing one account or separate accounts. That clears it up for me. Separate is the way to go for me.

Lastly, John, I want to give a great big thank you! You are doing an incredible work, John. I want you to know that my children and children’s children will be financially better off because of the work you are doing. I share that with you because I hope that in times of reflection, you can have a big smile on your face and great warmth in your heart knowing that people will be financially better off because of what you are doing. You are greatly appreciated. I sincerely thank you!

Ned

Awesome, yep, sorry I should have clarified; yes, Vanguard’s Total World Stock Market fund. It’s about as simple, efficient, and effective as it gets for a young investor with a long time horizon. Globally diversified across stocks and they can say they own over 8,500 stocks in their portfolio.

Wow, Ned, thanks so much for the kind words! They mean more than you know. It’s comments like yours that keep me motivated to do this stuff and remind me why I’m doing it.

I agree with Ned. Thank you for all the explanations. Even though I’m from Mexico, the information is sooo useful. Thank you!

Thanks, Gab!