The U.S. stock market isn't always king, and it doesn't really matter if it has been historically. Here I'll explain why that's the case and why it's probably a prudent idea for U.S. investors to also invest in international stocks.

Disclosure: Some of the links on this page are referral links. At no additional cost to you, if you choose to make a purchase or sign up for a service after clicking through those links, I may receive a small commission. This allows me to continue producing high-quality content on this site and pays for the occasional cup of coffee. I have first-hand experience with every product or service I recommend, and I recommend them because I genuinely believe they are useful, not because of the commission I may get. Read more here.

Contents

Video

Prefer video? Watch it here:

Introduction

Make no mistake that the U.S. stock market usually dominates the global market in terms of sheer size. At their market weights, U.S. stocks usually comprise a little over half of the global stock market. But that doesn't at all mean that we should ignore the other half.

International stocks don't move in perfect lockstep with U.S. stocks, offering a potential diversification benefit. If U.S. stocks are declining, international stocks may be doing well, and vice versa. This is particularly important for retirees.

If you're reading this, chances are you're in the U.S. You also probably overweight – or only have exposure to – U.S. stocks. Most Americans do. The data says most U.S. portfolios are about 80% U.S. stocks. This is called home country bias.

But remember that the U.S. is only one single country out of nearly 200 in the world. By solely investing in one country's stocks, the portfolio becomes dangerously exposed to the potential detrimental impact of that country's political and economic risks. If you are employed in the U.S., it's likely that your human capital is also highly correlated with the latter. Holding stocks globally diversifies these risks and thus mitigates their potential impact.

For U.S. investors, diversifying globally in stocks is also a way to diversify currency risk and to hedge against a weakening U.S. dollar, which has been gradually declining for decades. International stocks tend to outperform U.S. stocks during periods when the value of the U.S. dollar declines sharply, and U.S. stocks tend to outperform international stocks during periods when the value of the U.S. dollar rises. Just like with the stock market, it is impossible to predict which way a particular currency will move next.

“U.S. Companies Get Revenues From Abroad”

“But U.S. companies do business overseas,” people exclaim. I’ve always found this argument pretty silly, though I do recognize that it sounds reasonable on the surface.

First, the economy is not the stock market, and specifically, GDP and stock returns have had a slightly negative correlation historically. We care about how international stock markets behave relative to the U.S. stock market. That imperfect correlation is the entire point of diversification.

The fact that some U.S. firms get revenues from abroad means next to nothing. Coca-Cola is going to behave like a U.S. stock at the end of the day regardless of the fact that its sales are global in scope. Of course, this should be common sense. Stocks tend to respond to local economic and geopolitical events much more than events that occur outside their country of domicile.

By that logic, international companies do a lot of business with the U.S., so I guess we don't need U.S. stocks…

Excluding stocks outside the U.S. also means you’re missing out on leading companies that happen to be based elsewhere, which include some of the largest automotive and electronics companies in the world.

Besides, even if we concede that U.S. multinational firms aren't perfectly correlated with the U.S. market, we inarguably get a lower correlation by just buying international stocks. Many U.S. multinational firms also make efforts to hedge away currency fluctuations of their foreign operations. While this can help smooth revenue, foreign exchange itself can be a source of diversification for the portfolio.

Lastly, people seem to overlook the fact that concentrating in the U.S. presents more sector risk, because America doesn't produce everything. A US-only portfolio is severely lacking in revenue exposure to industries like semiconductors, technology hardware, household products, and materials.

As an added bonus, international stocks tend to be a better inflation hedge than U.S. stocks, for the simple reason that one country's inflation issues may not affect another.

So let's put this one to rest. Buying multinational companies ≠ international diversification.

Performance

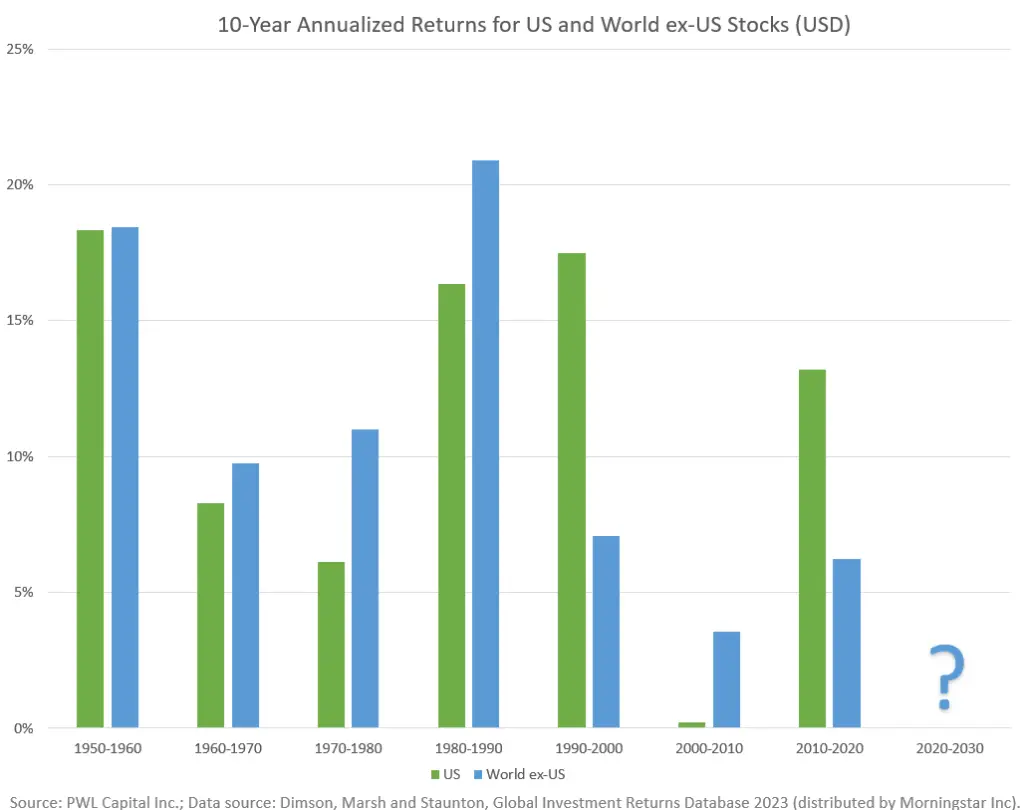

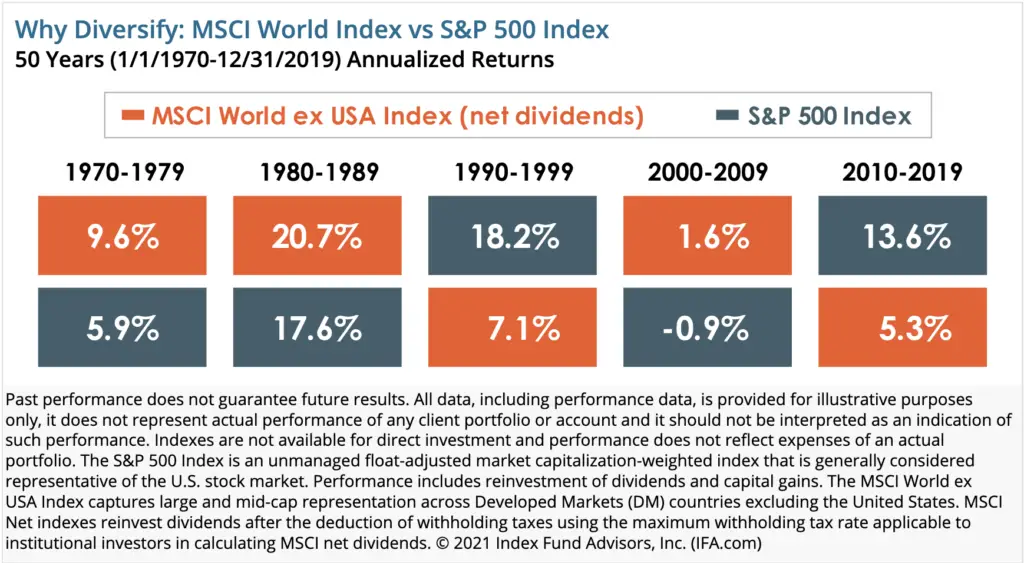

No single country's stock market consistently outperforms all the others in the world. If one did, that outperformance would also lead to relative overvaluation and a subsequent reversal, even if that reversal may be slow to happen. The legendary Meb Faber found that if you look at the past 70 years, the U.S. stock market has outperformed foreign stocks by 1% per year, but all of that outperformance has come after 2009.

Put another way, the U.S. stock market has lagged the international stock market in 5 of the last 7 decades:

There have also been periods where a global portfolio outperformed a U.S. portfolio. During the period 1970 to 2008, for example, a global portfolio of stocks had higher general and risk-adjusted returns than a U.S. stocks portfolio. That's the beauty of diversification using imperfectly correlated assets.

And this is just talking about performance. The volatility and risk reduction benefits are another conversation entirely, which is of huge significance for a retiree. Some will say geographic correlations tend to converge during crashes, and that's true, but it misses the point. We're not really concerned with short-term crashes, but rather with protracted bear markets, as the latter is more detrimental to our long-term goals. Cliff Asness et al echoed these exact sentiments in their 2010 paper titled International Diversification Works (Eventually).

Consider a retiree during the famous Lost Decade of 2000-2009. While U.S. stocks finished that time period down 10%, ex-US Developed Markets were up 11% and Emerging Markets were up a whopping 155%. The story was basically the same for the period 1968-1982, when the U.S. saw runaway inflation. In that sense, global diversification may make for a higher safe withdrawal rate in retirement by mitigating sequence risk.

Notice how U.S. or international outperformance tends to be cyclical:

If I were writing this in 2010 (or 1990, or 1980), we'd be talking about how a global portfolio beat a U.S. portfolio the previous decade. The important takeaway is that it's impossible to know when the performance pendulum will swing and for how long, much less how those time periods would match up with your personal time horizon and retirement date.

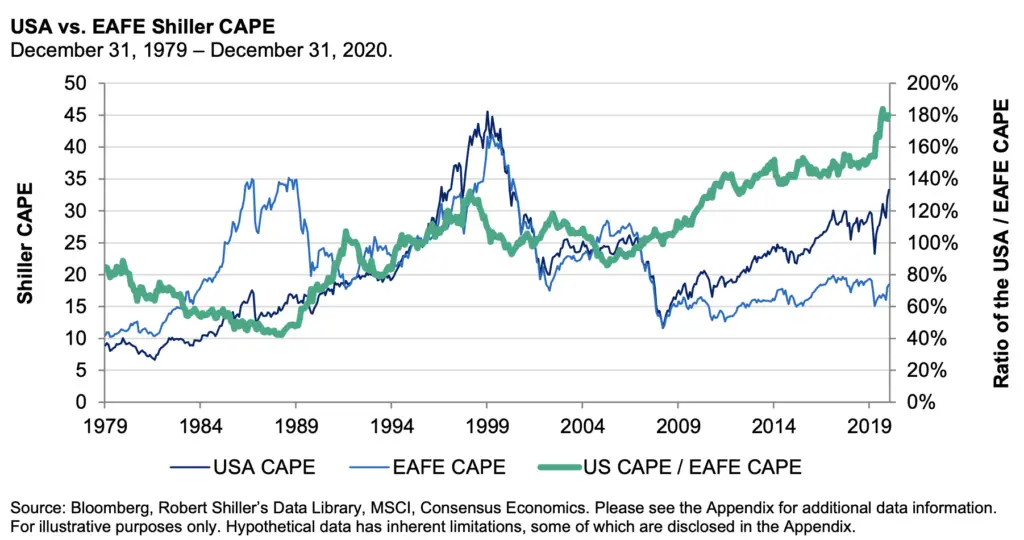

Moreover, U.S. stocks' outperformance on average over the past half-century or so has simply been due to increasing price multiples, not an improvement in business fundamentals. That is, U.S. companies did not generate more profit than international companies; their stocks just got more expensive. And remember what we know about expensiveness: cheap stocks have greater expected returns and expensive stocks have lower expected returns.

In the interest of full disclosure, at this point I would be remiss not to also mention that current valuations would predict international markets beating the U.S. market in the coming years, as the U.S. market is looking relatively expensive and international markets are looking relatively cheap. And despite what folks who don't understand how markets work seem to think, the U.S. market can't just get comparatively more expensive forever, as we're still paying for a discounted sum of future cash flows at the end of the day. This inevitability is made more apparent by the fact that most U.S. investors massively overweight U.S. stocks in their portfolios.

To add insult to injury on this tangent, these same people often exhibit a lot of narrative bias by having some explanation for why things happened in the past and why they will continue that way in the future, such as citing the U.S. having the most favorable environment for business. But again, these people seem to forget the simple fact that more buying drives up prices, and higher prices necessarily mean lower expected returns.

But one of the primary points of this post is that we don't try to time things around here and we don't try to predict the future, and I don't want current valuations that favor international stocks to seem like a crutch for any part of my argument, so now that you've heard it, please immediately disregard it. If you do have a working crystal ball, I'd love to borrow it.

As long-term buy-and-hold investors (you are one, right?), as a rule, we don't try to time the market. This includes trying to time U.S. versus international. Remember that all known information is immediately reflected in a stock's price, and the movement thereof is mostly a random walk, meaning the market's performance yesterday, last week, last month, or last year tells us nothing about what it will do tomorrow, next week, next month, or next year.

Because of this, recognize that while it may be tough and will likely cause some cognitive dissonance, we must acknowledge that the U.S. market's long term outperformance in recent years has nothing to do with today's decision to diversify globally going forward. I can't stress this enough, and this is arguably the most important piece of this entire post.

Here's a quick thought experiment to illustrate this point further. Suppose we knew nothing of the past performance of these markets relative to each other before today (or of any individual stock's performance as well for that matter). How should we invest? The most agnostic approach would be to simply buy all stocks in the investable universe and let the markets sort out their weights, which is what a market cap weighting scheme is. Market cap weighting isn't required, but it provides a starting point from which to titrate up or down for an allocation you're comfortable with.

I noted at the top that the U.S. market makes up a little over half of the global stock market right now. But that hasn't always been the case. It dropped to about 30% in the 1980's. Were that to happen again, which is entirely possible, the U.S. investor would inherently be missing out on a greater percentage of the global opportunity set.

Hopefully it strikes you as obvious that betting entirely on one single country would be a statistically silly bet in this context, especially when that bet specifically relies on investors continuing to be willing to pay more for one country's stocks, as discussed previously. Unfortunately, many young investors do precisely that, usually because they're simply chasing recent performance. These investors typically don't have any concrete plan and are thus highly susceptible to buying based on emotion.

Performance chasing usually results in long-term underperformance because, as discussed earlier, you're always buying the thing that recently went up in price that now has lower expected returns. A contrarian approach – buying what did poorly recently – may actually yield better long-term results, but again I'm not suggesting we should try to predict anything based on valuations.

Using a real-world example to hammer this point home about concentration, Australian stocks have beaten U.S. stocks historically, yet it should be obvious that we probably shouldn't go all in on those either.

In point of fact, for any given year, the best-performing stock market is usually not the United States. The U.S. market has been the best-performing market in only 2 of the last 15 years:

- 2008 – Japan

- 2009 – Brazil

- 2010 – Chile

- 2011 – New Zealand

- 2012 – Poland

- 2013 – USA

- 2014 – Egypt

- 2015 – Hungary

- 2016 – Brazil

- 2017 – Poland

- 2018 – Brazil

- 2019 – USA

- 2020 – Korea

- 2021 – India

- 2022 – Chile

Investing globally means you get exposure to whichever of these markets performs best year to year, a benefit that is not captured by simply looking at correlations. And of course, there's no predictable pattern for who's on top each year.

You'll notice many of those countries listed above are Emerging Markets. Conveniently, Emerging Markets tend to have unique developmental risks and characteristics that offer a reliably lower correlation to U.S. stocks than developed countries do. While one can make the argument that correlations of ex-US Developed Markets and the U.S. market have been increasing due to globalization, this is not entirely true of Emerging Markets, and arguably even less so for small cap value stocks globally, which is great for factor investors like myself.

These unique risks of Emerging Markets also mean greater expected returns; Emerging Markets have paid a significant risk premium historically. I delved into Emerging Markets in detail in a separate post here.

Risks and Overcoming Biases

But again, I would submit that the risk consideration is more important than caring about which country's market has the highest return, which can only be known in hindsight.

Over the past century, investors concentrated in a single country saw their portfolios completely wiped out by geopolitical events or debt crises, while other countries remained resilient. Japan's stock market still hasn't fully recovered from its catastrophic crash in the early 1990's, after it was once the largest stock market in the world. Russia and Germany offer other historical examples. If you think the U.S. is somehow immune to those things, you're fooling yourself.

I've noted elsewhere that broad diversification is the solution to reducing tail risk from black swan events. Wouldn't you rather rest easy at night knowing your portfolio is insulated against such risks?

Moreover, what I noted earlier that is just as important or arguably more important is that for extended horizons, one of the biggest risks for a US-only investor is the U.S. market severely underperforming, which is also entirely possible, especially with high expectations already priced in. And we can again eliminate that risk by simply buying other countries.

Don't let biases like familiarity bias, optimism bias, and recency bias derail your retirement. We can also blame authority bias here, as the suggestion of a US-only portfolio for retail investors has come from both Warren Buffett and the late Jack Bogle.

As an aside, savvy Bogleheads have figured all this out, which is where the default “VT and chill” mantra comes from. Ironically, this simplistic approach is more likely to yield superior risk-adjusted returns while mitigating unfavorable outcomes. In terms of geographic location, the VTI investor is still putting all her eggs in one basket. A large, robust basket, to be sure, but a single one nonetheless.

Again, this agnostic approach can be a large behavioral hurdle to overcome if you're just looking at sheer performance over the last 30 years or so. So let's circle back and expand even further on that “blank slate” assumption and I'll try to alleviate any potential tracking error regret – regret from underperforming some common benchmark – that might occur in the future as a result. After all, an entire generation of global investors has had to grapple with the fact that their long-term returns have been lower than that of a U.S. stocks portfolio while simultaneously trying to cling on to the belief in the merits of diversification.

Suppose you decide to invest globally today and then 20 years from now, U.S. stocks have still outperformed the global portfolio. You will likely feel like you made the “wrong” choice. This is known as outcome bias, which describes the tendency to irrationally evaluate a decision based on its subsequent outcome rather than on its merits at the time the decision was made. Recognize that the ex post observation of the unfavorable outcome has nothing to do with the rationality of the original decision to invest globally. Again, in this context, we choose to be agnostic on any given day regardless of what happened yesterday or over the past 30 years.

Put another way, while it may sound ridiculous, observing the hypothetical long-term outperformance of U.S. stocks over the past 100 years would tell us nothing about year 101, and investing globally would still be a prudent idea.

And to show you that I don't just talk the talk, I myself use a 50/50 split of U.S. to international stocks in my own portfolio.

Conclusion

Hopefully at this point I've convinced you that global diversification in equities has huge potential upside and little downside for investors, that U.S. companies receiving foreign revenues doesn't get us there, and that U.S. outperformance hasn't been as juicy as it appears at first glance due to the evolution of valuations.

If we're honest with ourselves, most investors would probably rather be able to sleep easy at night knowing their wealth is insulated against unpredictable black swan events and extended bear markets. Those who don't acknowledge the non-zero probability of such risks are simply underestimating them, either purposely or accidentally.

Any purveyor of market history will recognize the tangible benefits of global diversification, but it can still be a large behavioral hurdle for novice investors in the face of recent performance. Remember that past performance does not indicate future results, so rationally it should have no bearing on today's decision to diversify globally going forward.

And since you may be wondering at this point, aside from a global stock market fund like Vanguard's VT, I've listed some of the most popular ETFs for international stocks here.

What do you think of the idea of international diversification for U.S. investors? What does your portfolio look like? Let me know in the comments.

Disclaimer: While I love diving into investing-related data and playing around with backtests, this is not financial advice, investing advice, or tax advice. The information on this website is for informational, educational, and entertainment purposes only. Investment products discussed (ETFs, mutual funds, etc.) are for illustrative purposes only. It is not a research report. It is not a recommendation to buy, sell, or otherwise transact in any of the products mentioned. I always attempt to ensure the accuracy of information presented but that accuracy cannot be guaranteed. Do your own due diligence. I mention M1 Finance a lot around here. M1 does not provide investment advice, and this is not an offer or solicitation of an offer, or advice to buy or sell any security, and you are encouraged to consult your personal investment, legal, and tax advisors. Hypothetical examples used, such as historical backtests, do not reflect any specific investments, are for illustrative purposes only, and should not be considered an offer to buy or sell any products. All investing involves risk, including the risk of losing the money you invest. Past performance does not guarantee future results. Opinions are my own and do not represent those of other parties mentioned. Read my lengthier disclaimer here.

Are you nearing or in retirement? Use my link here to get a free holistic financial plan and to take advantage of 25% exclusive savings on financial planning and wealth management services from fiduciary advisors at Retirable to manage your savings, spend smarter, and navigate key decisions.

I thought it would be helpful to source Meb Faber’s comment on US outperformance here in the comments for other readers to see.

https://mebfaber.com/2019/07/08/i-dont-feel-overweight/

Any reason you use a 50/50 split of US/international instead of holding them at their market cap weights (which is currently ~59/41)?

Just sort of easier for how I want to construct, i.e. overweighting Emerging Markets and small cap value stocks. I’m not opposed to global market cap with something like VT.