Bonds are usually held in a portfolio with equities to reduce volatility and to offer downside protection against black swan events. Let's dive right into comparing corporate bonds and government bonds.

In a hurry? Here are the highlights:

- Corporate bonds are more volatile than government bonds.

- Government bonds are also called treasury bonds.

- Interest from government bonds is exempt from state and local taxes, while interest from corporate bonds is not.

- Treasury bonds offer a reliably lower correlation to equities than corporate bonds.

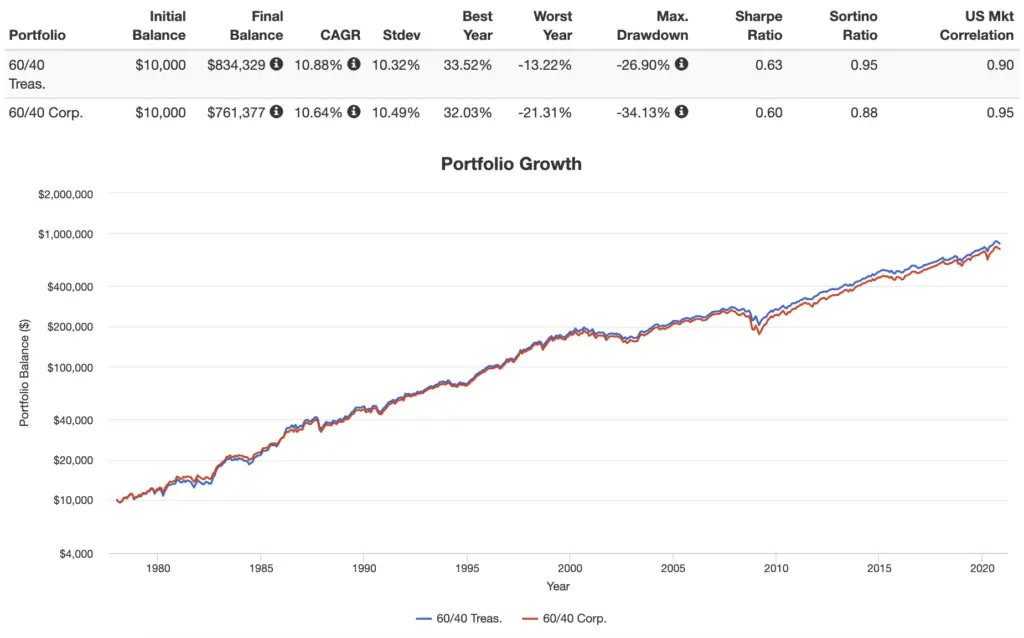

- Compared to corporate bonds, a traditional 60/40 portfolio using treasury bonds has historically resulted in higher returns, lower volatility, higher risk-adjusted returns (Sharpe), and smaller drawdowns.

- Many investors incidentally hold corporate bonds simply because of the convenience, popularity, and availability of total bond market funds that contain some allocation of corporate bonds.

- Municipal bonds tend to behave like corporate bonds in periods of market turmoil.

- Treasury bonds should be preferable to corporate bonds in a long-term diversified portfolio, and have the added benefits of allowing you to avoid state and local taxes, credit risk, liquidity risk, and default risk that accompany corporate debt.

Contents

Video

Prefer video? Watch it here:

Introduction and Assumptions

Let's start with some basic assumptions for the foundation of this discussion:

- Stocks tend to have higher returns than bonds.

- Bonds – also called fixed income – are used as a diversifier in investment portfolios, held alongside stocks to reduce portfolio volatility and risk and to protect against drawdowns and black swan events.

- Investors should be attempting to optimize the portfolio as a whole (specifically, things like CAGR, volatility, max drawdown, and risk-adjusted return as measured by Sharpe), not assets held in isolation.

- Classes of bonds include government debt (also called treasury bonds or treasuries) and corporate debt (bonds issued by companies, e.g. Microsoft), among others, each with its own unique correlation to equities.

On the whole, corporate bonds have historically delivered ever-so-slightly higher pre-tax returns (on paper) than treasury bonds. It's been theorized that this is due to a “tax premium” to compensate for state and local taxes, a liquidity premium due to their comparatively lower trading volume, and a risk premium considering corporate issues are riskier than U.S. government debt.

One would think it would follow that higher portfolio returns can be achieved by pairing stocks with corporate bonds, but that's actually not the case. The reason for this lies in asset correlations and specific types of risks.

Correlations, Liquidity Risk, Credit Risk, and Default Risk

Recall from high school math class that the bivariate correlation coefficient (aka the Pearson correlation coefficient or “Pearson's r”) is a measure of the linear correlation between two variables, with possible values between -1 and 1. A correlation coefficient of -1 means perfect negative correlation or inverse correlation. A correlation coefficient of 1 means perfect positive correlation. A correlation coefficient of zero means no correlation, or uncorrelation.

The reason bonds tend to reduce volatility within a portfolio alongside equities is precisely because of their possessing negative correlation – or at least uncorrelation – to equities on average over the long term. Over the past 30 years or so, long-term treasury bonds have had a fairly reliable negative correlation to stocks of approximately -0.5 on average, compared to 0.1 for corporate bonds.

It has been noted that this uncorrelation of government bonds is even conveniently amplified during times of market turmoil, which researchers referred to as crisis alpha. From 1926 to 2015, US long-term treasury bonds had a monthly correlation to US equities of 0.09, compared to 0.19 for US long-term corporate bonds. In months when US stocks generated a negative return, these correlations were 0.00 and 0.36, respectively.

This is due to the famous “flight to safety” behavioral effect wherein investors flock to bonds – specifically treasury bonds – when stocks are falling, thereby bidding up the price of treasuries. Probably the best example of this was the 2008 Global Financial Crisis. When stocks fell over 37%, intermediate-term treasury bonds rose 13%, intermediate investment-grade bonds fell 6%, and high-yield corporate bonds fell 21%. All things being equal, a portfolio using treasury bonds should reliably outperform a portfolio using corporate bonds in times of market turmoil. This is why ETFs like SWAN and NTSX use government bonds.

I'll illustrate all this correlation stuff with a graph in a second.

Moreover, the 2008 financial crisis also showed us that corporate bonds do indeed present significant liquidity risk during periods of market turmoil, for which investors are not adequately compensated. This illustrated that equity risk and credit risk are related, and that corporate bonds do not do their job at the precise time you need them to (when stocks are crashing). Think of credit risk as a potential downgrade of a bond's credit rating, which would result in a drop in the bond's value. Just as with stocks, corporate bonds seem to possess significant tail risk. The credit risk for treasuries is essentially zero, as they're backed by the full faith and credit of the U.S. government.

Albeit unlikely, corporate bonds – especially junk bonds – also have a risk of default. This means there is a non-trivial possibility that companies that issue bonds are unable to meet their debt obligations. As you can imagine, when this does happen, it tends to be in times of crisis. In the Dotcom crash of 2000, several large telecom companies defaulted on their bonds. Once again, corporate bonds tend to drop the ball just when we need them the most, and once again, the default risk of U.S. treasury bonds is virtually zero. In the interest of full disclosure, this default risk is itself an identified factor for fixed income portfolios, but as we've seen, it is not one you need to own.

Again, looking at bonds alone, corporate bonds tend to compensate investors over the long term – though not commensurately – for taking on these extra risks that government bonds don't have, which is why they tend to pay slightly more. But also keep in mind that this potential outperformance in isolation of corporate bonds comes at the cost of greater volatility and risk. The whole point of holding bonds in a diversified portfolio is usually to reduce volatility and risk. Moreover, corporate bonds tend to suffer precisely when we need them most, during stock market crashes. A common Bogleheads reference is to “take the risk on the equities side.” I don't necessarily subscribe to that exact adage, as I still use mostly long-term treasury bonds which are riskier than short-term treasury bonds, but I currently have no reason to hold corporate bonds in my portfolio.

These differences are amplified in a taxable environment, as interest from treasury bonds is tax-free at the state and local levels, while interest from corporate debt is not.

Speaking of taxation, let's briefly talk about municipal bonds, or munis, in this context. These bonds are popular among high income earners due to their federal-tax-free interest. This usually means their yield is lower than that of a taxable bond. More important to our discussion here, though, is the fact that while we would expect municipal bonds to have less credit risk and liquidity risk than corporate bonds, they still tend to behave a lot like corporate bonds during market crashes and don't offer much protection.

Corporate Bonds vs. Government Bonds – Performance Backtest

Here's a backtest going back to 1978 using a traditional 60/40 portfolio, one using long-term government bonds and one using long-term corporate bonds. If you didn't understand the bit above about the different correlations and the benefit of the lower correlation of treasury bonds, this will illustrate it. As we'd expect based on the points I raised above, the portfolio with treasury bonds (in blue below) comes out with a higher return, lower volatility, higher risk-adjusted return (Sharpe), and considerably smaller max drawdown (from the Subprime Mortgage Crisis of 2008):

Why Do People Hold Corporate Bonds?

Due to the inherent higher volatility of corporate debt, it has been shown that, pre-tax, holding corporate bonds over government bonds is basically the same as an additional 2 percent weighting to equities. I've been saying this for years – I view corporate bonds as somewhat of a halfway point between stocks and treasuries. A portfolio containing stocks and bonds invariably requires a higher corporate bond allocation (compared to treasuries) for the same degree of volatility reduction and downside protection.

So why does anyone hold corporate bonds?

I can think of a few reasons why they might:

- For some reason, the entire portfolio may be 100% bonds and the investor wants more risk/reward within those bonds.

- The investor is using bond interest as income and is utilizing a high-yield corporate bond fund.

- Probably the most likely, the investor is invested in a total bond market fund, such as Vanguard's BND, within a lazy portfolio or target date fund. Investors simply may not know – or may not care – that total bond market funds usually contain about 25-30% corporate debt. This case is likely simply borne of the convenience, popularity, availability, and seeming simplicity of total bond market funds, especially considering investors may not want to or may not know how to choose the appropriate duration of their bond allocation. Recent products like the iShares U.S. Treasury Bond ETF (GOVT), which is a total government bond market fund, offer a meaningful solution here. Investors may also erroneously (and understandably) believe that owning different types of bonds in a total bond market fund alongside stocks makes for a more diversified portfolio, which we've shown here to be false. While it may seem counterintuitive, diversifying within an asset class does not necessarily make that asset class a better diversifier for the portfolio as a whole.

Conclusion

In conclusion, utilizing government bonds should be preferable to corporate bonds due to their superior volatility reduction and downside protection abilities in a long-term diversified portfolio, and government bonds have the added benefits of allowing you to avoid state and local taxes, credit risk, liquidity risk, and default risk that accompany corporate debt.

If you have someone managing your investments or if you just use a target date fund, hopefully this at least has you curious about what your fixed income allocation looks like. You don't necessarily need to be able to recite to your cousin at Thanksgiving dinner that treasury bonds tend to have a lower correlation to stocks than corporate bonds, or that treasury bonds also conveniently tend to exhibit crisis alpha during market crashes, but now you can tell them what the graph above shows – that diversified portfolios using treasury bonds tend to outperform those using corporate bonds, all while conveniently having a lower risk profile.

References

Swedroe, Larry. 2014. “Swedroe: Fixed Income’s Low Risk Anomaly.” ETF.com, posted April 23 at etf.com/sections/index-investor-corner/21862.html?nopaging=1.

Swedroe, Larry. 2016. “Swedroe: Reconsidering Corporate Bonds.” ETF.com, posted July 15 at etf.com/sections/index-investor-corner/swedroe-reconsidering-corporate-bonds?nopaging=1.

Stivers, Chris, and Licheng Sun. 2002. “Stock Market Uncertainty and the Relation Between Stock and Bond Returns.” Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta working paper 2002-3, available at https://www.optimizedportfolio.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/10.1.1.197.4328.pdf.

Philips, Christopher B., David J. Walker, and Francis M. Kinniry Jr. 2012. “Dynamic Correlations: The Implications for Portfolio Construction.” Vanguard research paper available at https://www.optimizedportfolio.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/dynamic-correlations.pdf.

Fama, Eugene F., and Kenneth R. French. 1993. “Common Risk Factors in the Returns on Stocks and Bonds.” Journal of Financial Economics 33 (1): 3–56.

Connolly, Robert, Chris Stivers, and Licheng Sun. 2005. “Stock Market Uncertainty and the Stock-Bond Return Relation.” The Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 40 (1): 161–194.

Disclaimer: While I love diving into investing-related data and playing around with backtests, this is not financial advice, investing advice, or tax advice. The information on this website is for informational, educational, and entertainment purposes only. Investment products discussed (ETFs, mutual funds, etc.) are for illustrative purposes only. It is not a research report. It is not a recommendation to buy, sell, or otherwise transact in any of the products mentioned. I always attempt to ensure the accuracy of information presented but that accuracy cannot be guaranteed. Do your own due diligence. I mention M1 Finance a lot around here. M1 does not provide investment advice, and this is not an offer or solicitation of an offer, or advice to buy or sell any security, and you are encouraged to consult your personal investment, legal, and tax advisors. Hypothetical examples used, such as historical backtests, do not reflect any specific investments, are for illustrative purposes only, and should not be considered an offer to buy or sell any products. All investing involves risk, including the risk of losing the money you invest. Past performance does not guarantee future results. Opinions are my own and do not represent those of other parties mentioned. Read my lengthier disclaimer here.

Are you nearing or in retirement? Use my link here to get a free holistic financial plan and to take advantage of 25% exclusive savings on financial planning and wealth management services from fiduciary advisors at Retirable to manage your savings, spend smarter, and navigate key decisions.

John,

Have your views on the role of bonds changed in any way as a result of the significant increase over the last 18 months or so? More specifically :

1. Investment grade is now paying 9% which is similar to equity returns whilst Treasuries paid 4.5/5% which is 2/3 of the return on equities with much lower risk

2.. in the current circumstance is there a risk that long duration rates stay high even if low duration go down? In that case would you still prefer long duration?

Thanks very much

Would it be a viable strategy to, say, put half of a portfolio’s bonds in a specific long term treasury bond fund, and the other half in iShares GOVT? Thus presenting something of “tilt” towards length. Long-term TIPS would be another option (or could also be included). This seems logical to me, but I’m cautious about this falling into the trap of diversification for the sake of diversifying.

GOVT has an intermediate duration. Mixing it with long bonds just increases the average duration, which should be roughly matched to the investing horizon. No reason to overcomplicate it.

Given your point regarding the “tax premium” on corporates for state and local taxes, would living in an income tax-free state change your position on corporate vs. government bonds at all on the margin? Or is this too small of a consideration to overcome the correlation aspect? Thanks!

Great question, Thomas. Definitely wouldn’t change my position. Indeed, too small to overcome the correlation aspect.

Owning treasury bonds that lose to inflation, issued by a bankrupt government, can’t be repaid except in a debased declining currency, under the control of a corrupt congress, an incompetent Treasury Secretary, and the corrupt Federal Reserve is insane.

There will be no flight to safety – because the cause is a result of correcting a massive bond bubble due to decades of manipulated interest rates. If the stock market corrects – why invest in what is causing the correction – rising yields.

I own Microsoft and JNJ because they “will” pay me back.

There is no where to hide in the correction of a manipulated economy – and especially in assets issued by the manipulator.

Noted.

John, Thanks for your in-depth analyses and easy to understand write-ups.

I’m a few months from 65 and retirement. Currently I’ve reallocated to a 60-40 stock/bond portfolio. 40% of my bind side is intermediate treasuries (SCHR, VGIT) and the rest is a mix of DODIX, TIPS, and a small allocation to corporates (DODIX has about everything, too). If I want to simplify and reallocate the bond side to all treasuries to reduce risk, should I add 20-30 year bonds or just go 100% intermediates. And use for T bills also?

Thanks!

Thanks for the comment, Greg. I can’t provide personalized advice. I like the idea of half treasuries and half TIPS in retirement. I touched on this briefly here.

This would be a disaster of a portfolio. Investing in manipulated overpriced assets that provide only a small fraction of inflation is not the way to invest for or live in retirement.

What “portfolio” are you referring to? No one is going to be invested in 100% bonds, at least hopefully not.

Hi John, thanks for the thorough write-up.

Do you have any advice for non-US investors thinking of following your advice on diversification via long-term government bonds?

Some issues I’m wondering about:

– using bonds of the country of residence vs. international bonds

– importance of currency exchange costs given low bond returns

– persistence of the term factor in US vs. non-US bonds

Hey Olivier, thanks for the comment. Admittedly I’m not well-versed in what’s optimal for a non-US investor when it comes to bonds. I’d think the highest credit quality of the US Treasury is “valuable” but I’m not sure if that outweighs any exchange costs. Also depends on the tax environment, obviously. Sorry I couldn’t help more.

Thank you, John for such incredible resource. You blog is awesome.

I am 40 years old and just starting my investment journey )

I choose to start with lazy portfolio : 60% US Stocks (VTI), 20% ExUS Stocks (VXUS) – and 20% total bond market (BND) until I had read your article about treasury bond.

So now I see that treasury bonds best suit for diversification but I am concerning which to choose from two types long or intermediate duration.

What do you think is it a good idea to start with 20% of Long duration bonds then part of bond allocation move from long to intermediate duration in 10 years? Or decrease stock part of portfolio and add 10% of intermediate bonds. In this case at age 50 we receive 70% stocks, 20 Long bonds and 10 intermediate bonds.

Or it’s better to start with intermediate duration bonds?

Thanks, Alex! All things being equal, bond duration should be matched to the investing horizon, e.g. if I’m retiring in 10 years I’d want intermediate bonds. But at low allocations of 10-20%, I’m a fan of using long bonds because their greater volatility is better able to hedge against stock crashes. So my preference is to have the first 10-20% in long bonds. Hope this helps!

Thanks again for sharing information with us. Your website is fabulous!

Which treasury bonds would I invest in? They are showing negatives in YTD versus corporate bonds. Why would I invest in treasury bonds now? VGIT is -2.02 YTD , -2.09 1 year. What kind of bonds or other do I invest in now ?

Muni bonds , VWITX, help high earners. How much is consider high income earners? Which tax bracket, 32%?

Thanks,

Patty

Whichever ones are appropriate for your asset allocation and time horizon. I’m of the mind that bond duration should increase as allocation decreases, e.g. long for 10% and intermediate for something like 40%. All things being equal, duration should be matched to the time horizon of the liability.

Same reason one always would: portfolio stability and/or income. Granted, bonds per se probably aren’t a great investment at current yields, but that doesn’t mean they won’t still do their job of mitigating portfolio volatility and risk.

What you’re looking for is called “tax equivalent yield” of taxable bonds. Compare that to the muni yield if you’re looking to use them as income. Otherwise, probably go with treasuries. Munis are much more correlated with stocks.

Thanks for the analysis on 60/40 using corporate vs. treasuries. Really helped clarify the point that as a diversifier for bad times, treasuries are the way to go. What are your thoughts or analysis on munis? Do they behave more like corporate bonds during bad times?

Thanks, Michelle. Yep, munis tend to behave like corporates during downturns. Their primary use is tax-free income for those in high tax brackets.

Excellent, well written, easy to understand. Your article showed up on a google search. Good job. thanks.

Thanks, Bob!

Very nice work John

I am from Canada, and would like to know your thoughts on IShares Convertable Bond. ICVT

Thanking you,

James

Thanks, James! I’ll look into that fund and get back to you.

So convertible bonds are usually issued by unpredictable companies, usually in the tech sector, e.g. Tesla. They’re highly correlated with stocks, so it’s not going to provide downside protection like traditional bonds would. You’re basically taking on equity risk combined with junk bond risk characteristics. This fund in particular looks too concentrated in tech for my tastes.