Everyone always asks how I invest my own money. Some have basically pieced it together from various mentions across the blog, but I finally got around to laying it out in detail. I've named it the Ginger Ale Portfolio.

Interested in more Lazy Portfolios? See the full list here.

Disclosure: Some of the links on this page are referral links. At no additional cost to you, if you choose to make a purchase or sign up for a service after clicking through those links, I may receive a small commission. This allows me to continue producing high-quality content on this site and pays for the occasional cup of coffee. I have first-hand experience with every product or service I recommend, and I recommend them because I genuinely believe they are useful, not because of the commission I may get. Read more here.

Contents

Foreword – A Brief History of My Investing Journey

I hate when recipe websites tell an unnecessary, long-winded story before getting to the recipe, so feel free to skip straight to the portfolio by clicking here.

Starting around age 18, I spun my wheels for nearly a decade stock picking and trading options on TradeKing (which Ally later acquired), usually underperforming the market. I was naive and egotistical enough to think that I could outsmart and out-analyze other traders, at least on average.

Unfortunately, a math degree with a focus in statistics strengthened my faulty conviction for a few more years before I finally converted to index investing. Thinking back on that time and the way I traded (I don't think I can even call it investing) makes me cringe now, so these days I try to do whatever I can to help others – particularly new, young investors – avoid those same pitfalls I succumbed to. I'd be much further ahead now had I just indexed from the start.

Since I had previously only traded U.S. securities and entirely ignored international assets, when I converted to index investing, I went 100% VTI for the total U.S. stock market (U.S. companies do business overseas, right?) and wrote myself an Investment Policy Statement (IPS) to avoid stock picking as a hard rule going forward. I was also still tempted to try to time the market using macroeconomic indicators and by selectively overweighting sectors around this time before realizing that sector bets are just stock picking lite, market timing tends to be more harmful than helpful, and the broad index fund does the self-cleansing and sector rearranging for me.

Then I dug deeper into the Bogleheads philosophy and realized I was still being ignorant by avoiding international stocks (more on this below), so I decided to throw in some VXUS at about 80/20 U.S. to international. I kept reading and researching and digging and concluded that I still had way too much home country bias. The U.S. is only one country out of many around the world! So I switched to 100% VT. Global stock market, market cap weighted. Can't go wrong. And “100% VT” would still be my elevator answer for a young investor just starting out.

Then I got further into the nuances of evidence-based investing as well as the important behavioral aspects of investing and what the research had to say about these things – Fama and French, Markowitz and MPT, efficient markets, leverage, Black and Scholes, Merton Miller, asset allocation, risk tolerance, sequence risk, factors, dividend irrelevance, asset correlations, risk management, etc.

I started realizing that, in short, 100% VT is objectively suboptimal in terms of both expected returns and portfolio risk. Emerging Markets only comprise 11% of the global market. Small cap stocks make up an even smaller fraction. And we should probably avoid small cap growth stocks. And certain funds have superior exposure to Value than others based on their underlying index's selection methodology. And can I stomach the drawdowns that accompany a 100% cap weighted stocks position during a crash? This line of thinking led me to books and lazy portfolios from present-day advisors like William Bernstein, Larry Swedroe, Ray Dalio, Paul Merriman, and Rick Ferri, all of whom influenced my thought process and subsequent portfolio construction.

I also realized there's an observable tradeoff between simplicity and optimization. I'm a tinkerer by nature and tend to default to the latter, probably to a fault (i.e. overfitting and data mining), which is why this blog's name is what it is, for better or for worse. People say indexing is boring, but it doesn't have to be. There's still plenty of learning to be had, and subsequent research-backed improvements to be made in the pursuit of optimization if you choose to tinker.

But don't get me wrong. Simplicity is – and probably should be – a desirable characteristic of one's portfolio for most people. Whatever allows you to sleep at night, stay the course, and not tinker during market downturns is the best strategy for you. It can take some time (and probably a market crash) to figure out what that strategy is. The portfolio below will seem “simple” to a stock picker with 100 holdings; it may seem complex to the indexer who is 100% VT.

So below I've pieced together what I think is optimal for me, based on my understanding of what the research thus far has to say about expected returns, volatility, diversification, risk, cognitive biases, and reliability of outcome, all while realizing I may get it wrong and that I may want to change it in the future.

About the Ginger Ale Portfolio

Update July 2021: Got way too many emails from people using this portfolio and then asking me about TIPS and Emerging Markets gov't bonds (what they are, what they're for, etc.). They clearly didn't understand what they were buying. That's not good. So I removed those pieces.

I'm bad at thinking of clever names for things. When writing posts, I usually sip on a can of ginger ale, so the Ginger Ale Portfolio seemed like an appropriate name.

Aside from “lottery ticket” fun money in the Hedgefundie Adventure and my taxable account in NTSX, this portfolio is basically how my “safe” money is invested. Leverage, while perhaps useful on paper for any investor, is probably not appropriate for most investors purely because of the emotional and psychological fortitude its usage requires during market turmoil.

Thus, for a one-size-fits-most portfolio, I can't in good conscience just recommend a leveraged fund. Moreover, whatever I put below will likely just be blindly copied by many novice investors who won't even bother reading or understanding the details, so I have to take that fact into consideration and be at least somewhat responsible.

This portfolio is 90/10 stocks to fixed income using a long duration bond fund to, again, accommodate sort of a one-size-fits-most asset allocation for multiple time horizons and risk tolerances. I'd call it medium risk simply because it has some allocation to fixed income. It is a lazy portfolio designed to match or beat the market return with lower volatility and risk.

It heavily tilts toward small cap value to diversify the portfolio's factor exposure. It is also diversified across geographies and asset classes. Specifically, this portfolio is roughly 1:1 large caps to small caps and for U.S. investors, it has a slight home country bias of 5:4 U.S. to international, nearly matching global market weights.

In selecting specific funds, I looked for sufficient liquidity, appreciable factor loading (where the expected premium would outweigh the fee), low tracking error, and low fees.

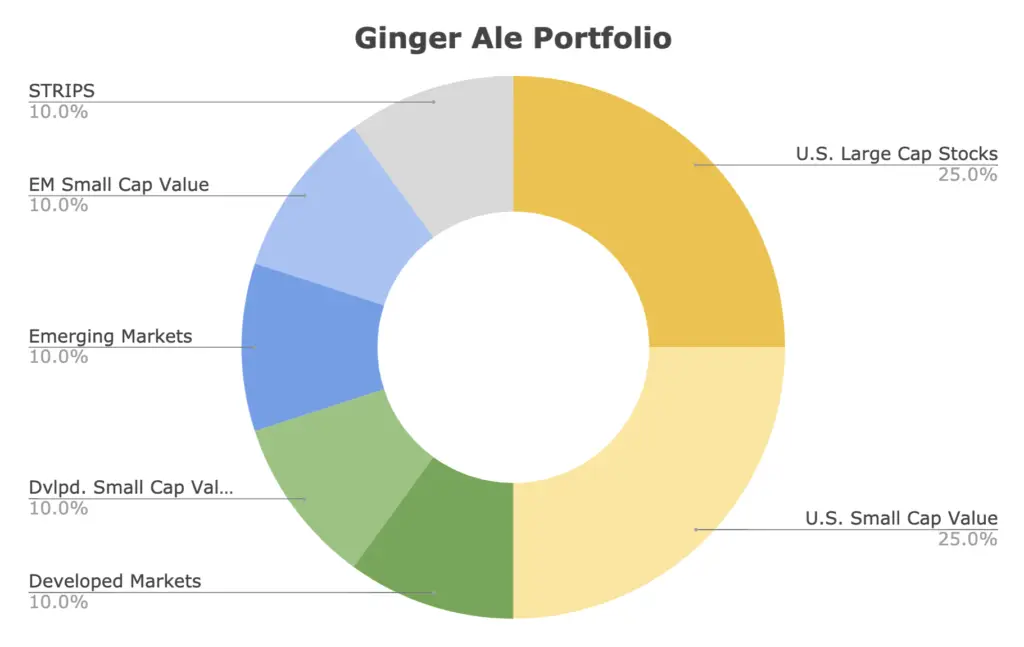

Here's what it looks like:

Ginger Ale Portfolio Allocations:

- 25% U.S. Large Cap Stocks

- 25% U.S. Small Cap Value

- 10% Developed Markets (ex-US)

- 10% Developed Markets (ex-US) Small Cap Value

- 10% Emerging Markets

- 10% Emerging Markets Small Cap Value

- 10% U.S. Treasury STRIPS

Below I'll explain the reasoning behind each asset in detail.

U.S. Large Cap Stocks – 25%

Most lazy portfolios use U.S. stocks – and specifically large-cap U.S. stocks – as a “base.” This one is no different, but they're still only at 25%. You'll see why later.

Not much to explain here. The U.S. stock market comprises a little over half of the global stock market and has outperformed foreign stocks historically. I don't feel comfortable going completely small caps for the equities side so we're keeping large caps here to diversify across cap sizes, as large stocks beat small stocks during certain periods, while small stocks beat large stocks over other periods.

This segment captures household names like Amazon, Apple, Google, Johnson & Johnson, Microsoft, etc. Specifically, we're using the S&P 500 Index – considered a sufficient barometer for “the market” – via Vanguard's VOO.

Why not use VTI to capture the entire U.S. stock market including some small- and mid-caps? I'll answer that in the next section.

U.S. Small Cap Value – 25%

I don't use VTI (total U.S. stock market) because I want to avoid those pesky small-cap growth stocks which don't tend to pay a risk premium. Even mid-cap growth hasn't beaten large cap blend on a risk-adjusted basis. Using VTI would also dilute my target large cap exposure.

Specifically, small cap growth stocks are the worst-performing segment of the market and are considered a “black hole” in investing. The Size factor premium – small stocks beat large stocks – seems to only apply in small cap value. As Cliff Asness from AQR says, “Size matters, if you control your junk.” Basically, if you want to bet on small caps, the evidence suggests you want to do so in small cap value, preferably while also screening for profitability.

By “risk premium,” I'm referring to the independent sources of risk identified by Fama and French (and others) that we colloquially call “factors.” Examples include Beta, Size, Value, Profitability, Investment, and Momentum. I delved into those details in a separate post that I won't repeat here, but I'll be referring to these factors and their benefits quite a few times below. Though it may sound like magic, the evidence suggests that overweighting these independent risk factors both increases expected returns over the long term and decreases portfolio risk by diversifying the specific sources of that risk, as the factors are lowly correlated to each other and thus show up at different times. The reason I don't want to go 100% factors like Larry Swedroe is because A) I don't have the stomach and conviction he has, and B) there's always the possibility of being wrong.

I know the exclusion of mid-caps entirely seems bizarre at first glance too. Factor premia tend to get larger and more statistically significant as you go smaller. That is, ideally you want to factor tilt within the small cap universe. That's exactly what we're doing here by basically taking a barbell approach in U.S. equities: using large caps and small caps to put the risk targeting exactly where we want it while still diversifying across cap sizes and equity styles. Essentially, we're letting large caps be our Growth exposure in the U.S. and consciously avoiding small- and mid-cap growth stocks.

In short, small cap value stocks have smoked every other segment of the market historically thanks to the Size and Value factor premiums. “Value” refers to underpriced stocks relative to their book value. Basically, cheaper, sometimes crappier, downtrodden stocks have greater expected returns. Small cap value stocks are smaller and more value-y than mid-cap value stocks. Thus, no mid-caps. (As an aside, Alpha Architect basically takes this idea to the extreme – finding the absolute smallest, cheapest stocks and concentrating in only 50 of them; talk about a wild ride.)

I don't want it to seem like I think this is some profound, contrarian approach. Using VTI (total stock market) instead of VOO (S&P 500) would be perfectly fine, and at only 25% of the portfolio, the difference is admittedly probably negligible. The simple point is that I've already decided on a specific small cap allocation, and I'm choosing to get that exposure through a dedicated small cap value fund rather than through VTI. Similarly, I've also already decided on a specific “pure,” undiluted large cap allocation, and I'm choosing to get that exposure through the S&P 500 Index.

Previously, the S&P Small Cap 600 Value index (VIOV, SLYV, IJS) was basically the gold standard for the U.S. small cap value segment. AVUV, the new kid on the block from Avantis, has provided some extremely impressive exposure – superior to that of those funds – in its relatively short lifespan thus far, so much so that it recently replaced VIOV in my own portfolio. I went into detail about this in a separate “small value showdown” post here. In a nutshell, it has been able to capture smaller, cheaper stocks than its competitors, with convenient exposure to the Profitability factor, all while considering Momentum in its trades, and we would expect the premium to more than make up for its slightly higher fee.

Including small caps also took the famous 4% Rule up to 4.5% historically.

Developed Markets – 10%

Developed Markets refer to developed countries outside the U.S. – Australia, Canada, Germany, the UK, France, Japan, etc.

At its global weight, the U.S. only comprises about half of the global stock market. Most U.S. investors severely overweight U.S. stocks (called home country bias) and have an irrational fear of international stocks.

If you're reading this, chances are you're in the U.S. As I just pointed out, odds are favorable that you also overweight – or only have exposure to – U.S. stocks in your portfolio. The U.S. is one single country out of many in the world. By solely investing in one country's stocks, the portfolio becomes dangerously exposed to the potential detrimental impact of that country's political and economic risks. If you are employed in the U.S., it's likely that your human capital is highly correlated with the latter. Holding stocks globally diversifies these risks and thus mitigates their potential impact.

Moreover, no single country consistently outperforms all the others in the world. If one did, that outperformance would also lead to relative overvaluation and a subsequent reversal. During the period 1970 to 2008, an equity portfolio of 80% U.S. stocks and 20% international stocks had higher general and risk-adjusted returns than a 100% U.S. stock portfolio. Specifically, international stocks outperformed the U.S. in the years 1986-1988, 1993, 1999, 2002-2007, 2012, and 2017. For the famous “lost decade” of 2000-2009 when U.S. stocks were down 10% for the period, international Developed Markets were up 13%.

For U.S. investors, holding international stocks is also a way to diversify currency risk and to hedge against a weakening U.S. dollar, which has been gradually declining for decades. International stocks tend to outperform U.S. stocks during periods when the value of the U.S. dollar declines sharply, and U.S. stocks tend to outperform international stocks during periods when the value of the U.S. dollar rises. Just like with the stock market, it is impossible to predict which way a particular currency will move next.

Moreover, U.S. stocks' outperformance on average over the past half-century or so has simply been due to increasing price multiples, not an improvement in business fundamentals. That is, U.S. companies did not generate more profit than international companies; their stocks just got more expensive. And remember what we know about expensiveness: cheap stocks have greater expected returns and expensive stocks have lower expected returns.

Dalio and Bridgewater maintain that global diversification in equities is going to become increasingly important given the geopolitical climate, trade and capital dynamics, and differences in monetary policy. They suggest that it is now even less prudent to assume a preconceived bet that any single country will be the clear winner in terms of stock market returns.

In short, geographic diversification in equities has huge potential upside and little downside for investors.

I went into the merits of international diversification in even more detail in a separate post here if you're interested.

Vanguard offers a low-cost fund called the Vanguard FTSE Developed Markets ETF. Its ticker is VEA.

Developed Markets (ex-US) Small Cap Value – 10%

We can also specifically target small cap value in ex-US Developed Markets stocks. It costs a bit more to do so, and some who tilt small cap value in the U.S. don't feel the need to do so in foreign stocks, but I think it's a prudent move considering the factor premia – in this case Size and Value – have shown up at different time periods across different geographies throughout history.

Remember we also get a diversification benefit here in doing so; it's not just for the greater expected returns. The earnings of large international corporations are more closely tied to global market forces, whereas smaller companies are more affected by local, idiosyncratic economic conditions. This means they are perfectly correlated with neither their large-cap counterparts nor with U.S. stocks.

Until just about a year ago, an expensive dividend fund from WisdomTree (DLS) was arguably the best way to access this segment of the global market. Now, Avantis has launched a fund available to retail investors that specifically targets international small cap value – AVDV. It is the only fund available to the public that specifically targets Size and Value (and conveniently, Profitability) in ex-US stocks. AVDV is also roughly half the cost of the former option DLS.

Emerging Markets – 10%

Emerging Markets refer to developing countries – China, Taiwan, India, Brazil, Thailand, etc.

Investors sometimes shy away from these countries due to their unfamiliarity and greater risk. I would argue that makes them more attractive. Stocks in these countries have paid a significant risk premium historically, compensating investors for taking on their greater risk.

Arguably more importantly, Emerging Markets tend to have a reliably lower correlation to U.S. stocks compared to Developed Markets, and thus are a superior diversifier. Of course, we would expect this, as these developing countries have unique risks – regulatory, liquidity, political, financial transparency, currency, etc. – that do not affect developed countries, or at least not the same extent. I delved into this in a little more detail here. For the previously mentioned “lost decade” of 2000-2009 when the S&P 500 delivered a negative 10% return, Emerging Markets stocks were up 155%.

Emerging Markets only comprise about 11% of the global stock market. This is why I don't use the popular VXUS (total international stock market) – because its ratio of Developed Markets to Emerging Markets is about 3:1. Here we're using a 1:1 ratio of Developed to Emerging Markets.

Vanguard's Emerging Markets ETF is VWO.

Emerging Markets Small Cap Value – 10%

Just like we just did with Developed Markets above, we can focus in on small cap value stocks within Emerging Markets as well.

Here we’re using a small cap dividend fund from WisdomTree as a proxy for Value within small caps in Emerging Markets. Don’t let this sound discouraging. The fund also screens for liquidity and strong financials and has appreciable loadings across Size, Value, and Profitability. Factor investors are wise to this fact, as this fund boasts nearly $3 billion in assets.

The fund is DGS, the WisdomTree Emerging Markets SmallCap Dividend Fund.

Factor investors like myself thought AVES, Avantis’s newest offering for more aggressive factor tilts in Emerging Markets, might dethrone DGS when it launched in late 2021. While it’s certainly no slouch and would still be a fine choice, I still prefer the looks of DGS, even with its higher fee. I compared these specifically here.

U.S. Treasury STRIPS – 10%

No well-diversified portfolio is complete without bonds, even at low, zero, or negative interest rates.

By diversifying across uncorrelated assets, we mean holding different assets that will perform well at different times. For example, when stocks zig, bonds tend to zag. Those 2 assets are uncorrelated. Holding both provides a smoother ride, reducing portfolio volatility (variability of return) and risk. We used the same concept above in relation to risk factor exposure. Now we're talking about entirely separate asset classes, but we're also taking advantage of a risk premium in fixed income: term. I delved into the concept of asset diversification in detail in a separate post here.

STRIPS (Separate Trading of Registered Interest and Principal of Securities) are basically just bonds where the coupon payment is rolled into the price, so they are zero-coupon bonds. Here we're using a fund that is essentially just very long duration treasury bonds (25 years).

I can see the waves of comments coming in, which I see all the time on forums and Reddit threads:

- “Bonds are useless at low yields!”

- “Bonds are for old people!”

- “Long bonds are too volatile and too susceptible to interest rate risk!”

- “Corporate bonds pay more!”

- “Interest rates can only go up from here! Bonds will be toast!”

- “Bonds return less than stocks!”

So why long term treasuries? Here are my brief rebuttals to the above.

- Bond duration should be roughly matched to one's investing horizon, over which time a bond should return its par value plus interest. Betting on “safer,” shorter-term bonds with a duration shorter than your investing horizon could be described as market timing, which we know can't be done profitably on a consistent basis. This is also a potentially costlier bet, as yields tend to increase as we extend bond duration, and long bonds better counteract stock crashes. More on that in a second.

- Moreover, in regards to bond duration, we know market timing doesn't work with stocks, so why would we think it works with bonds and interest rates? Bonds have returns and interest payments. A bond's duration is the point at which price risk and reinvestment risk – the components of what we refer to as a bond's interest rate risk – are balanced. In this sense, though it may seem counterintuitive, matching bond duration to the investing horizon reduces interest rate risk and inflation risk for the investor. An increase in interest rates and subsequent drop in a bond's price is price risk. A decrease in interest rates means future coupons are reinvested at the lower rate; this is reinvestment risk. A bond's duration is an estimate of the precise point at which these two risks balance each other out to zero. If you have a long investing horizon and a short bond duration, you have more reinvestment risk and less price risk. If you have a short investing horizon and a long bond duration, you have less reinvestment risk and more price risk. Purposefully using one of these mismatches in expectation of specific interest rate behavior is intrinsically betting that your prediction of the future is better than the market's, which should strike you as unlikely.

- It is fundamentally incorrect to say that bonds must necessarily lose money in a rising rate environment. Bonds only suffer from rising interest rates when those rates are rising faster than expected. Bonds handle low and slow rate increases just fine; look at the period of rising interest rates between 1940 and about 1975, where bonds kept rolling at their par and paid that sweet, steady coupon.

- Bond pricing does not happen in a vacuum. Here are some more examples of periods of rising interest rates where long bonds delivered a positive return:

- From 1992-2000, interest rates rose by about 3% and long treasury bonds returned about 9% annualized for the period.

- From 2003-2007, interest rates rose by about 4% and long treasury bonds returned about 5% annualized for the period.

- From 2015-2019, interest rates rose by about 2% and long treasury bonds returned about 5% annualized for the period.

- New bonds bought by a bond index fund in a rising rate environment will be bought at the higher rate, while old ones at the previous lower rate are sold off. You're not stuck with the same yield for your entire investing horizon. The reinvested higher yield makes up for any initial drop in price over the duration of the bond.

- We know that treasury bonds are an objectively superior diversifier alongside stocks compared to corporate bonds. This is also why I don't use the popular total bond market fund BND.

- At such a low allocation of 10%, we need and want the greater volatility of long-term bonds so that they can more effectively counteract the downward movement of stocks, which are riskier and more volatile than bonds. We're using them to reduce the portfolio's volatility and risk. More volatile assets make better diversifiers. The vast majority of the portfolio's risk is still being contributed by stocks. Using long bonds also provides some exposure to the term fixed income risk factor.

- We're not talking about bonds held in isolation, which would probably be a bad investment right now. We're talking about them in the context of a diversified portfolio alongside stocks, for which they are still the usual flight-to-safety asset during stock downturns. It has been noted that this uncorrelation of treasury bonds and stocks is even amplified during times of market turmoil, which researchers referred to as crisis alpha.

- Similarly, short-term decreases in bond prices do not mean the bonds are not still doing their job of buffering stock downturns.

- Bonds still offer the lowest correlation to stocks of any asset, meaning they're still the best diversifier to hold alongside stocks. Even if rising rates mean bonds are a comparatively worse diversifier (for stocks) in terms of expected returns during that period does not mean they are not still the best diversifier to use.

- Historically, when treasury bonds moved in the same direction as stocks, it was usually up.

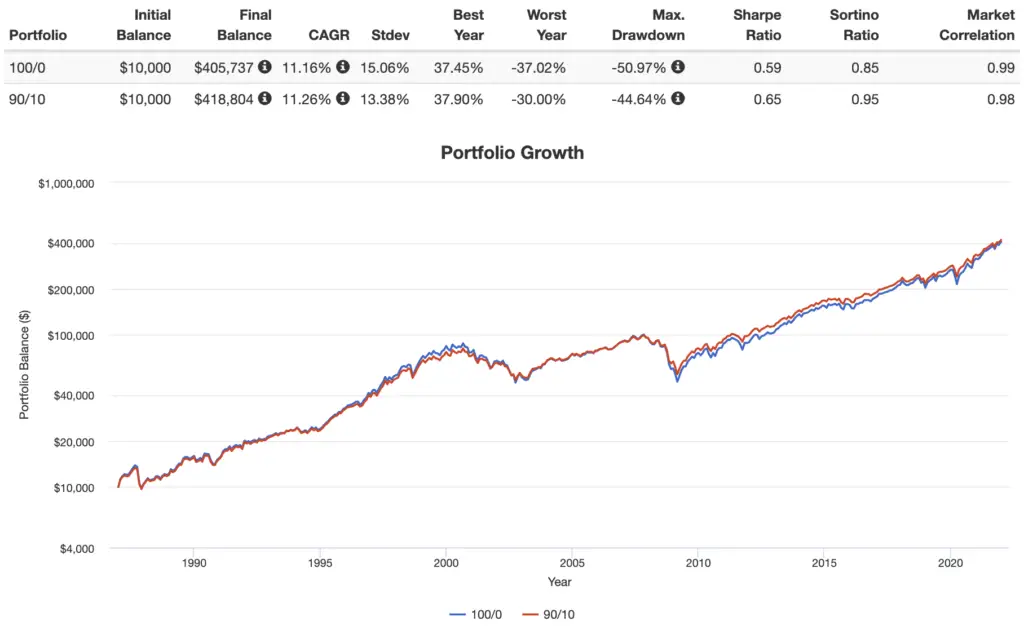

- Long bonds have beaten stocks over the last 20 years. We also know there have been plenty of periods where the market risk factor premium was negative, i.e. 1-month T Bills beat the stock market – the 15 years from 1929 to 1943, the 17 years from 1966-82, and the 13 years from 2000-12. Largely irrelevant, but just some fun stats for people who for some reason think stocks always outperform bonds. Also note how I've shown below that a 90/10 portfolio using STRIPS outperformed a 100% stocks portfolio on both a general and risk-adjusted basis for the period 1987-2021.

- Interest rates are likely to stay low for a while. Also, there’s no reason to expect interest rates to rise just because they are low. People have been claiming “rates can only go up” for the past 20 years or so and they haven't. They have gradually declined for the last 700 years without reversion to the mean. Negative rates aren't out of the question, and we're seeing them used in some foreign countries.

- Bond convexity means their asymmetric risk/return profile favors the upside.

- I acknowledge that post-Volcker monetary policy, resulting in falling interest rates, has driven the particularly stellar returns of the raging bond bull market since 1982, but I also think the Fed and U.S. monetary policy are fundamentally different since the Volcker era, likely allowing us to altogether avoid runaway inflation like the late 1970’s going forward. Stocks are also probably the best inflation “hedge” over the long term.

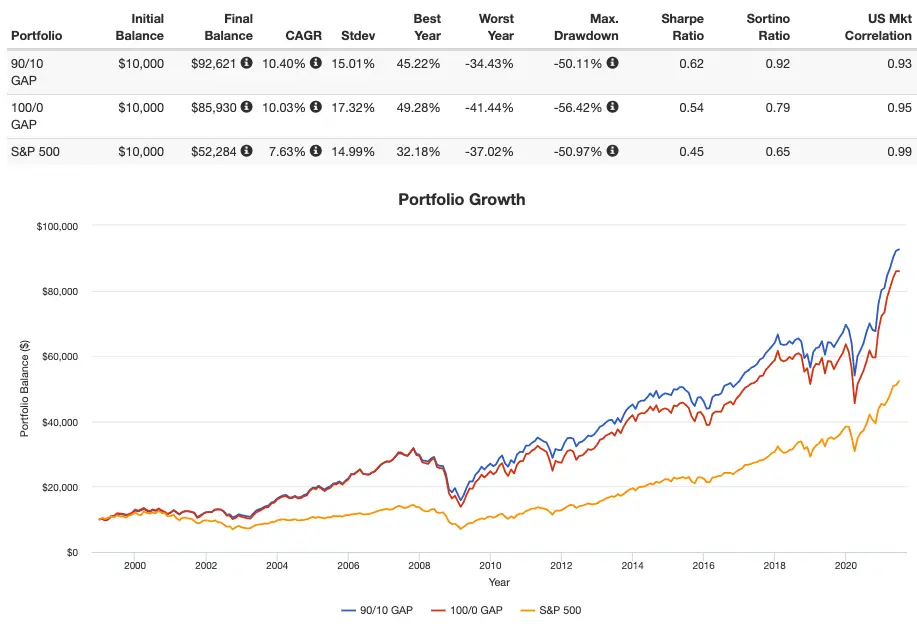

Here's that backtest mentioned above showing a 90/10 portfolio using STRIPS beating a 100% stocks portfolio for 1987-2021:

David Swensen summed it up nicely in his book Unconventional Success:

“The purity of noncallable, long-term, default-free treasury bonds provides the most powerful diversification to investor portfolios.”

Ok, bonds rant over.

For this piece, I'm using Vanguard's EDV, the Vanguard Extended Duration Treasury ETF.

Ginger Ale Portfolio – Historical Performance

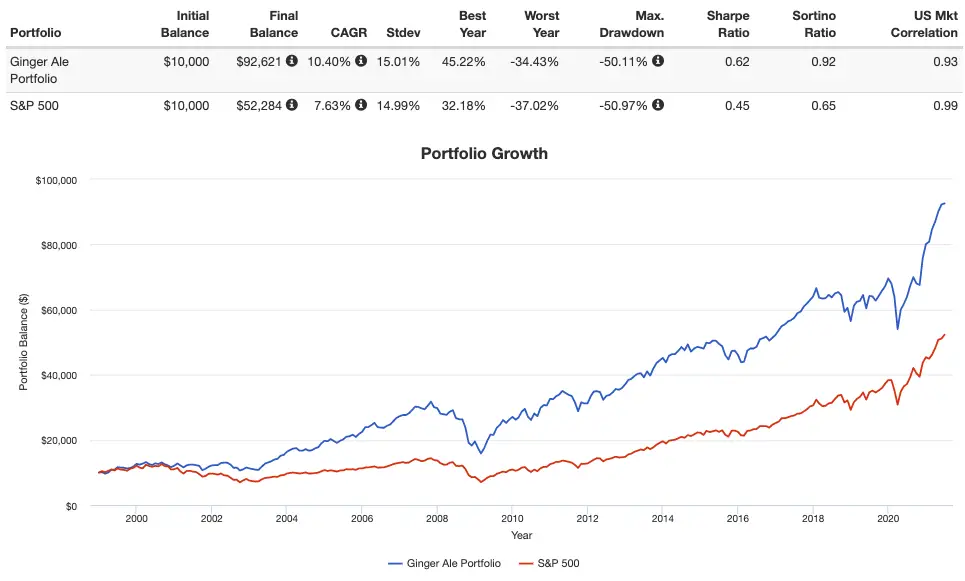

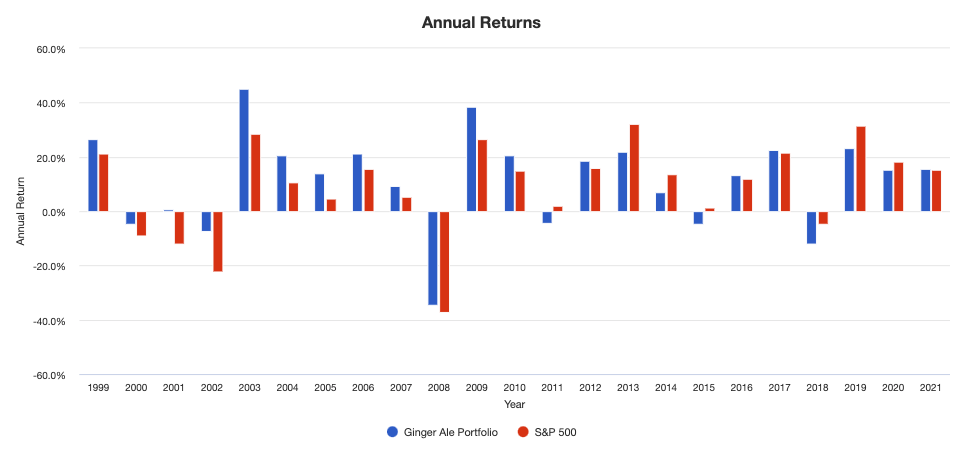

Some of these funds are pretty new, so I had to use comparable mutual funds from Dimensional in some cases to extend this backtest and give us a rough idea of how this thing would have performed historically. The furthest I could get was 1998, going through June 2021:

Here are the annual returns:

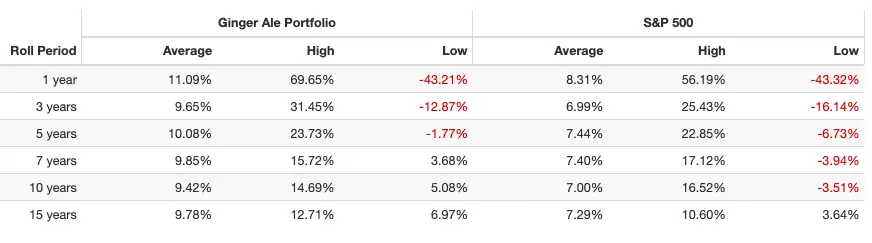

Here are the rolling returns:

Keep in mind the Size and Value premia and international stocks suffered for the decade 2010-2020, otherwise I think the differences in performance metrics would have been even greater.

Ginger Ale Portfolio Pie for M1 Finance

So putting the funds together, the resulting Ginger Ale Portfolio looks like this:

- VOO – 25%

- AVUV – 25%

- VEA – 10%

- AVDV – 10%

- VWO – 10%

- DGS – 10%

- EDV – 10%

You can add this pie to your portfolio on M1 Finance by clicking this link and then clicking “Save to my account.”

Canadians can find the above ETFs on Questrade or Interactive Brokers. Investors outside North America can use Interactive Brokers.

Being More Aggressive with 100% Stocks

I'd like to think I made a pretty good case for why you shouldn't fear bonds, but if you're young and/or you have a very high risk tolerance, you might still be itching to ditch the bonds and go 100% stocks. Here's a more aggressive version, basically giving an extra 5% each to VOO and AVUV for more of a U.S. tilt:

- VOO – 30%

- AVUV – 30%

- VEA – 10%

- AVDV – 10%

- VWO – 10%

- DGS – 10%

Here's the pie link for that one.

Just note that historically this would have resulted in worse performance than the original 90/10:

Incorporating NTSX, NTSI, NTSE

A lot of people know I'm a huge fan of WisdomTrees line of “Efficient Core” funds like NTSX and have explicitly asked about replacing the stocks index funds from the aggressive version with these new 90/60 funds from WisdomTree, so I've added this section to briefly address that. If this idea sounds foreign to you, maybe go read this post that explains how NTSX works first and then come back here.

Making those substitutions of the WisdomTree Efficient Core Funds (NTSX, NTSI, and NTSE) for the broad index funds for the S&P 500 (VOO), ex-US Developed Markets (VEA), and Emerging Markets (VWO) is absolutely fine, but I've tried to explain to a few people in the comments that this doesn't materially change the exposure too much from the original Ginger Ale Portfolio simply because EDV packs quite a volatile punch since it's extended duration treasury bonds. That was the whole point of its inclusion.

In other words, going 6x on intermediate treasury bonds (what the WisdomTree funds do) is nearly the same exposure as what EDV provides.

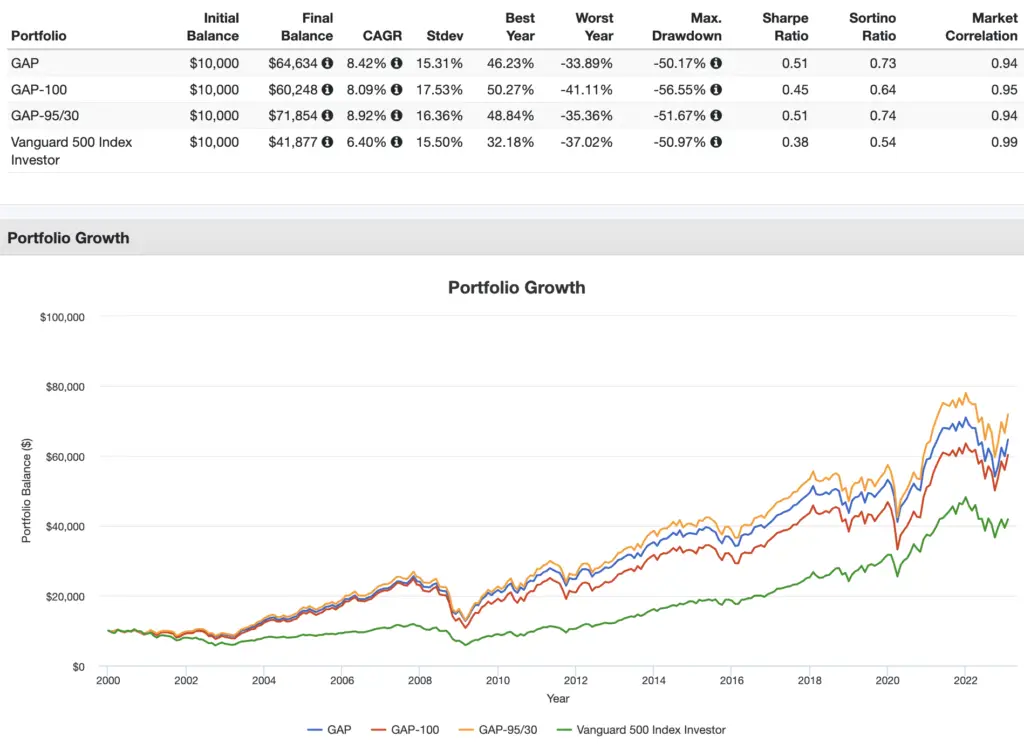

This is illustrated in the backtest below that shows the original Ginger Ale Portfolio, the aggressive 100% stocks version, and a version substituting in NTSX/NTSI/NTSE that delivers effective exposure of 95/35:

Making those substitutions, that 95/30 portfolio looks like this:

NTSX – 30%

AVUV – 30%

NTSI – 10%

AVDV – 10%

NTSE – 10%

DGS – 10%

Also keep in mind this one has a much greater expense ratio. You can get this pie here.

Adjusting This Portfolio For Retirement

I've also had a lot of people ask me how I plan to adjust this portfolio as I near and enter retirement. The answer is pretty simple and straightforward. I don't care about dividends or using them as income, so I plan to simply decrease stocks, increase bonds, decrease bond duration, add some TIPS, and sell shares as needed. Factor tilts and geographical diversification would remain intact.

For example, a 40/60 version using intermediate nominal and real bonds might look something like this:

- 10% VOO – U.S. Large Caps

- 10% AVUV – U.S. Small Cap Value

- 5% VEA – Developed Markets (ex-US)

- 5% AVDV – Developed Markets (ex-US) Small Cap Value

- 5% VWO – Emerging Markets

- 5% DGS – Emerging Markets Small Cap Value

- 30% VGIT – Intermediate U.S. Treasury Bonds

- 30% SCHP – Intermediate TIPS

That pie is here if you want it for some reason.

Are you nearing or in retirement? Use my link here to get a free holistic financial plan and to take advantage of 25% exclusive savings on financial planning and wealth management services from fiduciary advisors at Retirable to manage your savings, spend smarter, and navigate key decisions.

Questions, comments, concerns, criticisms? Let me know in the comments.

Disclosure: I am long VOO, AVUV, VEA, VWO, AVDV, DGS, and EDV.

Interested in more Lazy Portfolios? See the full list here.

Disclaimer: While I love diving into investing-related data and playing around with backtests, this is not financial advice, investing advice, or tax advice. The information on this website is for informational, educational, and entertainment purposes only. Investment products discussed (ETFs, mutual funds, etc.) are for illustrative purposes only. It is not a research report. It is not a recommendation to buy, sell, or otherwise transact in any of the products mentioned. I always attempt to ensure the accuracy of information presented but that accuracy cannot be guaranteed. Do your own due diligence. I mention M1 Finance a lot around here. M1 does not provide investment advice, and this is not an offer or solicitation of an offer, or advice to buy or sell any security, and you are encouraged to consult your personal investment, legal, and tax advisors. Hypothetical examples used, such as historical backtests, do not reflect any specific investments, are for illustrative purposes only, and should not be considered an offer to buy or sell any products. All investing involves risk, including the risk of losing the money you invest. Past performance does not guarantee future results. Opinions are my own and do not represent those of other parties mentioned. Read my lengthier disclaimer here.

Are you nearing or in retirement? Use my link here to get a free holistic financial plan and to take advantage of 25% exclusive savings on financial planning and wealth management services from fiduciary advisors at Retirable to manage your savings, spend smarter, and navigate key decisions.

Hi John,

I love the GAP. How do I run backtests on portfoliovisualizer / I keep getting messages i.e. The time period was constrained by the available data for

Find comparable mutual funds where possible to extend it. Look at Dimensional’s.

Hey John, long time follower of your blog and videos, really great stuff thank you for your contributions here. I have a maybe naive question. I understand the value of rebalance when it comes to HFEA in direct relationship with stock vs. bonds, but for Gingerale, I view it as a purely “set-and-forget” approach like holding VOO.

What is the rationale behind annual rebalancing? Why not let each of the markets run it’s course over a 30 year hold period. I am trying hard to convince myself that it’s sensible to sell VOO (to rebalance the other positions), despite all we’ve been told from Bogle/Buffet on holding the index. In my opinion it only makes sense to balance with the bonds (as stocks zig, bonds tend to zag), but as it relates to equity vs. other equities, curious to hear your thoughts on just letting it run it’s course.

Bogle even went as far to say “never rebalance your investments”. Curious to hear your thoughts. Video reference: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sO8SLwDOvCk&ab_channel=RobBerger

Rob Berger has a good video on this: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sO8SLwDOvCk&ab_channel=RobBerger

Thanks, Ed! Not a dumb question at all. First, admittedly not going to make a huge difference either way. In short, there’s a theoretical rebalancing bonus from uncorrelated volatile assets (see Bernstein paper here) but we’re not guaranteed to get it. Here we have stocks and long bonds, uncorrelated and both quite volatile. So not too different from the idea of rebalancing HFEA. Imagine stocks go up and bonds go down to where the portfolio here is 95/5, but our intended allocation is 90/10, so we’d need to rebalance. Whether or not that is optimal is unknown. But rebalancing is quite literally buying low and selling high. All else equal, an asset that goes up now has lower future expected returns, and an asset that goes down now has greater future expected returns. Though that’s not how our highly emotional brains usually think of it (see biases post). Even within equities alone it’d be the same idea, albeit less likely to get a “bonus.” Bogle had quite a few opinions that weren’t right. I delved into rebalancing a bit here. Hope this helps.

Hey John, thanks for the well thought-out reply. Read the papers on linked; rebalancing bonds / stocks make absolute sense! However I need more education on the rebalancing of US vs. international / EM equities (never seen this done before, or done it myself)

Curious if you have more to comment on that, and if you backtested a scenario where this was not rebalanced I am curious if that makes a difference

Hey John,

thanks for your work… it made me to understand well the value of broad diversification. I built a modified version of your gingerale portfolio more suited to my needs and I was doing some backtesting with portfolio visualizer. However, I`m not able to reproduce your charts. Do you have a link for the portfolio you used to show the comparison with SP500? I tried to use generic asset classes to go back in time as:

US Stock 25%

SCV 25%

International ex-US value 20%

European stock 10%

Emerging markets 10%

LTT 10%

However with this generic asset allocation this portfolio seems to under perform quite a lot as compared to a SP500. It is somehow comparable to a simple 75/25 instead. What am I missing here?

Is it possible that the over performance of your back testing is more related to the performance of each fund than the actual asset class?

Thanks !

John:

I have read many investing sites over the years but most recently came across yours and I’ve been amazed by not just the thought process but also the depth of the analysis and the approachable writing. Congratulations on great work and for sharing it. I found your site when searching for more information on the Bogleheads 3 fund portfolio and loved the other options for it you provided like Portfolio 3 (80/20 with VGLT). Have you done a head-to-head of that Portfolio 3 and the Ginger Ale Portfolio? I saw data from 1987-2019 for the former and 1987-2021 for the latter but it would be great to see them analyzed over the exact same timeframe.

Simon

Simon, thanks so much for the kind words! Glad you’ve found my ramblings useful. I haven’t run that exact comparison because they’re pretty different things for different investors.

Great post! What is your reasoning for not running this portfolio in your taxable account – and instead going for NTSX? Is there a big tax drag compared to NTSX?

Thanks JT! Yea, less tax efficient.

In your disclosure you have mentioned NTSX is majority of your taxable account but you’re saying it’s not and less tax efficient here. Did you change your strategy?

https://www.optimizedportfolio.com/ntsx/

Sounds like you’re misunderstanding my comment. NTSX is more tax efficient and comprises most of my taxable account. That has not changed.

I don’t see my other comment, but yes, I believe logical fallacy 15 applies in this case. Just because my investment blew up with a fund I thought was supposed to track the Russell 2000 value but declined much more doesn’t mean I should hold on to it. By indication, I mean I read your post and looked at the prospectus and other data on their site and did not suspect it would crash like a leveraged ETF.

To be frank, if you’re paying attention to and losing sleep over one week of price behavior, then this is the wrong strategy and the wrong website for you, and your risk tolerance is much lower than you initially thought. Consider consulting a professional advisor and buying mostly short term treasury bonds. Investing is a marathon. Moreover, if you thought AVUV “was supposed to track the Russell 2000 Value” index, that was a mistake. Avantis products are not index funds. Lastly, my point was that investors did not “suspect” or have an “indication” of a 50% drawdown in 2008, as no one has a crystal ball (to my knowledge). Best of luck.

I’m not sure if Avantis is having a company meltdown or what, but AVUV has me down 12% from buying in a week ago. I’m going to dump it and AVDC. I am caught off guard at how dangerous these funds are. I didn’t see any indication that they were about to collapse before I bought.

Ed, it sounds like you need to read this post, understand what you’re buying and why you’re buying it, take a long term view, and ignore the short term noise. Also not sure what “indication” would have existed.

I would like to propose an idea. It’s true that in isolation, large cap growth underperforms large cap value. But when I look at LCG paired with SCV, it performs better than LCB plus SCV. That’s 50 years of data. What would you think of replacing VOO with VUG (or similar)? Thanks

Jon, I’ve discussed this idea with some folks in the Rational Reminder community. First, to get this out of the way, I’m not sure what you’re seeing. Here’s the backtest I ran for that.

Now for the idea itself, here are my thoughts. I look at it from the other side of the coin in terms of evidence for exclusion – in my opinion we have no compelling evidence to exclude LCV entirely. A backtest isn’t sufficient evidence for such a conclusion. If we believe in Value enough to tilt SCV, why would we consciously exclude LCV? We also know SCV and LCV don’t always move together. If I hold VOO, for example, for LCB, and LCG takes off, my VOO holding naturally tilts Growth, as it did in recent years. But if I instead buy LCG specifically with something like VUG, I’m now concentrated in the style with lower expected returns and I’m also now less factor-diversified, e.g. HmL for the portfolio is going to be close to zero or only slightly positive (in the case of 50% LCG, 50% SCV, that is). Behaviorally, this also opens me up to more tracking error regret if LCV – of which I now own zero – does well.

In fact, I think one could just as easily – and perhaps more soundly – make the argument that we could flip it and go LCV and SCV and exclude LCG (Portfolio 3 here), but of course I probably wouldn’t do that either.

An idea that has been discussed in the RR community that’s along your line of thinking is to go roughly half SCV and half MOM with something like QMOM.

Dear John,

I would like to express my gratitude for the valuable insights you have shared on long-term investing. I have read through several of your posts and found them to be quite helpful in expanding my knowledge in this area.

I am writing to seek your expert opinion on my current 401k allocation strategy. Initially, I was attempting to set up an allocation plan between my 401k, IRA, and HSA accounts. However, as the value of my 401k has grown to a significantly higher percentage of my overall portfolio, I am finding it increasingly challenging to create a balanced allocation, especially given the limited options available in my 401k.

As a result, I have devised a theoretical 401k allocation plan consisting of the following funds:

Large Cap – iShares S&P 500 Index K – WFSPX – 25% (100/0)

Small Cap Value – DFA US Targeted Value I – DFFVX – 25% (99/1)

Developed Markets – Empower International Value Instl – MXJVX – 20% – (100/0)

Emerging Markets – American Funds New World Fund® Class R-6 – RNWGX – 20% (92/8)

Bond – PGIM Global Total Return Fund – Class R6 – PGTQX – 10% (3/97)

I am reaching out to you to see if you have any feedback on my plan. Do you think there is anything I should rework or consider? I am also considering the alternative of investing in a target date fund with a 0.5% expense ratio, which may be a simpler option.

I appreciate any insight you can provide on this matter, as I am committed to ensuring a well-balanced and diversified portfolio. Additionally, I would like to note that I plan to continue running my regular ETF allocation in my Roth, IRA, and taxable accounts.

Thank you for your time and expertise.

Glad to hear it, Justin. Thanks for the kind words! Unfortunately I can’t provide personalized advice. Best of luck.

Hi John, thanks for this and all your articles. This isn’t really to do with your portfolio, but I wondered if you could comment on what tends to separate funds that target the same factor? For example, AVUV has performed differently than VSIAX since the start of 2021. Not specific to this example, are performance differences generally because of the specific equities the fund happened to choose, the degree to which they target the factor/sector/geography (e.g., very small cap vs. small-medium cap), or something else?

Do you know if there are mutual funds that track similarly to DGS and AVDV?

Great question, Matt. So assuming the same geo (US, Emerging Markets, etc.), almost all of it comes down to factor loadings and fees in most cases. I delved into those nuances for U.S. small cap value specifically for AVUV and VBR here that should offer some useful insights. VBR is just the ETF equivalent of VSIAX. Dimensional does have some mutual funds for small cap value in Emerging Markets and Developed Markets.

1. AVDE instead of VEA or not worth the extra cost?

2. AVUS instead of VOO or the US large cap exposure gets diluted?

3. If not comfortable with the EM risk, can the EM allocation go evenly towards AVDV and VEA (or AVDE) instead?

Thank you!

Impossible to say for sure and up to you to decide. AVDE and AVUS over their cap weighted index cousins just means you’ve got more aggressive factor tilts toward Size, Value, etc. for the total portfolio.

Hey John! Can you please provide a link to portfolio visualizer for the back test on this portfolio with the funds you used?

Thank You!

I’ve always shied away from this because I don’t want novices to focus on, obsess over, quibble about, and start overfitting backtests, which tell us little about the future. The focus should be on the overall strategy and ideas of diversification and expected factor premia. As noted, Dimensional mutual funds should get you there.

I am having trouble re-creating the back-testing of your Ginger Ale Porfolio back to 1998. Can you post the specific proxy funds you used to test historical performance?

I’ve always shied away from this because I don’t want novices to focus on, obsess over, quibble about, and start overfitting backtests, which tell us little about the future. The focus should be on the overall strategy and ideas of diversification and expected factor premia. As noted, Dimensional mutual funds should get you there.

Can you elaborate more on why you prefer DGS to AVES? Does DGS capture the SCVEM premium better? How would you compare them in a taxable account?

Hey Josh, I talked about it here for EM Value and here for SCV – basically better loadings, lower market cap, lower P/E. AVES may be more tax efficient due to lower yield but I’m guessing it has higher turnover so I’m not entirely sure.

What are your thoughts on replacing DGS with AVES for the emerging markets SCV portion now that AVES has been out for a little longer?

I had forgotten to update this post to reflect the DGS vs. AVES question. I’ve updated it now. I still like DGS, though AVES looks good as well.

John, Will you be swapping any of the avantis or wisdomtree out for the new Dimensional etf funds?

Thank You!

Probably not.

How did you get to the backtest to go so far back to 2000? Could you share your portfoliovisualizer link?

I’ve always shied away from this because I don’t want novices to focus on, obsess over, quibble about, and start overfitting backtests, which tell us little about the future. The focus should be on the overall strategy and ideas of diversification and expected factor premia. As noted, Dimensional mutual funds should get you there.

Hey John –

Love your work! How did you back test with the Avantis funds as they’re relatively new (2019)?

Thanks! Used comparable Dimensional mutual funds as proxies.

How do you rebalance this portfolio?

Same as any other – sell overweight positions and buy underweight ones. If you use M1, it dynamically rebalances from new deposits and also has a one-click rebalance button.

Have you done a comparison of your Ginger Ale to a 90% SCHD 10% Strip portfolio. It appears to me the SCHD may be a simpler solution.

Thanks for a great site with very useful information.

Another behavioral stat nerd

Thanks, Patrick! I haven’t run that specific comparison, but I’d be hesitant to use SCHD as my only stocks exposure anyway because it’s basically just 100 U.S. large cap value stocks.

Hi John,

What exactly were the alternative ETFs you used to backtest the portfolio back t 1981?

Thanks for all the hard work!

Regards,

Joao

I’ve always shied away from this because I don’t want novices to focus on, obsess over, quibble about, and start overfitting backtests, which tell us little about the future. The focus should be on the overall strategy and ideas of diversification and expected factor premia. As noted, Dimensional mutual funds should get you there.

Hi John,

I appreciate your insights. I am 50 and for most of my working life I have been in VTSAX and VASGX.

I am currently in the mindset that we are due for a 20-25 percent correction in the DOW and we will not recover or record new highs over 36000 in this decade.

With this as your base thought how would you invest differently if at all?

I think value stocks, Int’l and short term treasuries will be best suited to preserve capital versus VTSAX.

Any opinion is appreciated .

Thanks

Thanks, Anthony. Market timing tends to be more harmful than helpful. I don’t try to do it. Best thing is usually to pick a strategy and stick with it.

John,

Is there a 60/40 version of your Ginger Ale portfolio anywhere? I am retired but your 40/60 version is more conservative than I care to be. Thanks!

Not specifically that I’ve made but you can adjust the allocations as you see fit.

I was thinking about what you might change with the “Ginger Ale Retirement Fund” if a couple in their 70’s don’t need the money except for nursing homes – maybe -in the future.. All I have been trying to do lately is find dividend funds–until you showed me I don’t need them. You sure put a lot of work and effort into everything you do on this site. I really appreciate it. .Charlie

Thanks for the kind words, Charlie! 🙂

I’m very interested in this portfolio and I love this article! Three questions:

1.) Have you moved to AVES, or still with DGS?

2.) Can you rank these ten funds for tax efficiency? I am trying to figure out which ones can function in taxable, and which ones should be in Roth or Trad/401k?

3.) Is VLGSX a satisfactory substitute for EDV?

Thanks, JB! 1. Still with DGS but AVES would be a fine choice too. 2. Probably VEA and VWO first since you’d get foreign tax credits, then VOO, then a toss up between the SCV funds, then bonds. 3. Similar but much lower duration.

Are you still using this portfolio? I thought you were heavily invested in NTSX.

Yes and I am.

Hey John, thanks very much for all the work on this site. I wanted to ask if you’d consider replacing NTSX, NTSI, and NTSE with an allocation to TYA (plus another alpha position). The stock portion of NTSX, NTSI and NTSE do not look to be anything special, and the fee for replacing that should be minimal. Or you could invest in more small cap value or other alpha. TYA seems to provide the leveraged bonds portion, which is the interesting part. Thoughts?

Just another way to skin that cat that I mentioned, I guess. NTSX, 90/10 VOO/TYA, and 90/10 VOO/EDV are all roughly equal in effective exposure, for example. We’d possibly get more carry premium from NTSX and TYA, but that’s not guaranteed, and those products are probably harder to understand for the average investor than EDV.